Earlier this year, real estate broker Chris Iverson pulled up to the gate in front of his record-breaking $85 million Portola Valley listing for a private showing. The buyer’s agent was already there, idling in a Tesla SUV. Then a black van arrived, a far more demure choice than the typical Bentley or Ferrari.

The three cars convoyed up the long driveway to the front of the 12,000-square-foot Tuscan-inspired main home, where a four-person security detail team emerged from the van and formed a perimeter. Only then did the potential buyer step out from the agent’s gull-winged Tesla and reveal herself.

She was a petite Chinese woman of a certain age, dressed head to toe in Saint Laurent, Hermes, and Fendi. Iverson is no fashion expert, but he knew the brands because the tags were still attached, a cultural quirk meant to assure that there’s no mistaking luxury labels, even from afar.

Iverson doesn’t speak Mandarin, but he could read her body language during the tour. It was clear she loved the primary closet, which is the size of a one-bedroom condo, modeled after a Chanel boutique, and doubles as a bomb- and bullet-resistant panic room.

The prospective buyer had been planning to leave the area right away but held her private plane on the tarmac a bit longer to pore over the 12-acre estate.

In retrospect, Iverson thinks the remote setting left her cold — too much of a “disconnect” from her home in Shanghai.

“She was going, ‘Wait, there’s deer in the yard? Where’s the nearest stoplight? Four miles away?’” he said.

Iverson remembers during the housing boom before the 2008 financial crisis when mini tour buses full of Chinese investors would caravan through open houses on the Peninsula, led by guides speaking Mandarin and stopping in for just five minutes at a time.

That “mania” slowed as the Chinese government began tightening restrictions to prevent citizens from taking their money out of the country, before coming to a near-halt during the Covid pandemic.

Now, these buyers are returning. But the difficulty of steering cash out of China means that only the highly connected, ultra-wealthy are hunting for prestige properties.

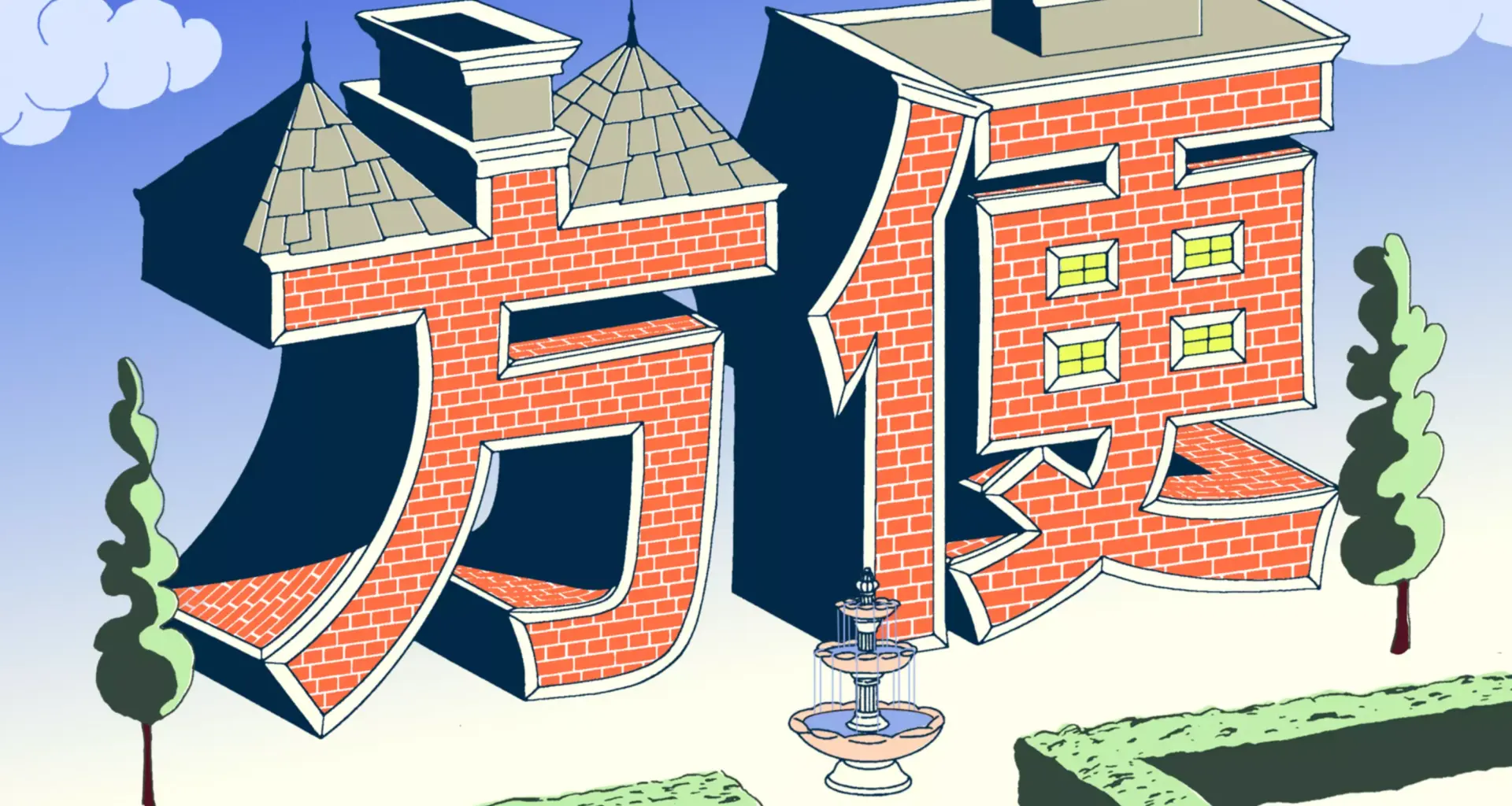

In this new, crazy rich Asian era of Bay Area real estate, status symbols, familiarity, and, above all, fang bian, a Chinese take on convenience, are prized. And still — even amid a resurgent time for the city — San Francisco is largely off the table.

Ups and downs

Chinese interest in the American real estate market peaked in 2017. That year, Chinese nationals spent $31.7 billion buying 40,600 U.S. homes, according to the National Association of Realtors (NAR). That’s 20% of the volume for all foreign residential real estate investment that year and nearly $13 billion more than the second-biggest foreign investor pool, Canadians.

It was part of a mad dash to get money out of China as the government began shutting down exit strategies when capital outflows hit a record $725 billion in 2016, according to the Institute of International Finance. A government crackdown to protect the yuan soon targeted everything from overseas deals to cross-border withdrawals.

By 2019, spending on U.S. residential real estate by Chinese nationals was down more than half from 2017 levels to $13.4 billion, according to NAR.

Then Covid hit. Amid the financial and travel restrictions, strained ties between the U.S. and China, and the inability to travel internationally, real estate investment by Chinese nationals dropped to a 10-year low of $4.8 billion in 2021. Chinese interest has been crawling back ever since. This year’s sales volume has topped 2019 levels.

California has been one the main beneficiaries of that renewed enthusiasm: 57% of international buyers in the state are from Asia or the South Pacific. One in three Chinese buyers of U.S. homes choose California.

As it has become increasingly difficult to get funds out of China, buyers are skewing more affluent. The average purchase price for a Chinese buyer in the U.S. in 2025 was nearly $1.2 million, about $450,000 more than the average for all foreign buyers. A decade ago, before the restrictions were in place, the average purchase price for a Chinese national in the U.S. was $590,000.

The methods for getting funds out of China now involve everything from tucking gold bars into carry-on bags to buying Hong Kong insurance products similar to certificates of deposit. Chinese buyers have also shown up in Tokyo with suitcases of money to buy apartments, according to a 2023 story in The New York Times that quoted a Japanese real estate listing service executive lamenting how difficult it was to count up the millions in cash.

Iverson heard about a recent case in which a Chinese clothing manufacturer had 50 employees each send the maximum $50,000 bank transfer (opens in new tab) under Chinese law to the escrow company to fund his Peninsula home purchase.

“The government figures out, oh, here’s how we’re leaking wealth and assets, and so they close that loophole,” he said. “People are creative and ingenious, so then they find the next loophole, and the economy springs another leak.”

What’s in a name?

Those leaks are making it rain in the Peninsula’s most affluent real estate markets, where agents say Chinese buyers once again make up a significant portion of interest in top-tier homes.

“When I’m hosting an open house in the mid-Peninsula, Mandarin is probably the language that the buyers who come through are speaking about 50% of the time,” said Sotheby’s agent John Young, who often uses lucky 8s in asking prices to connect with East Asian buyers.

Among their demands? “Name brand” locations with international reputations. That essentially boils down to Palo Alto for the rich and Atherton for the even richer. It’s the real estate equivalent of subtly showing off the red soles of your Louboutins. Tell people you bought in Menlo Park or Los Altos, and you’ll get a bunch of blank stares.

Even Woodside, where estates can sell for $40 million and up, typically doesn’t make the grade.

“Getting to a nice address in Woodside is not a longer Uber ride from SFO than downtown Palo Alto or the middle of Atherton,” Young said. “They’re about the same, but the perception is, ‘Woodside is way too far out there, and there’s nothing out there for me.’”

The perception of San Francisco is even less flattering, as word of the city’s glow-up has not yet made it to many international buyers.

“I think there is the ongoing stigma of San Francisco,” said Young, citing issues with fentanyl, homelessness, and street crime.

The fact that Young and Iverson both work for Sotheby’s is another indication of brand importance for this clientele. Neither speaks Mandarin or Cantonese — though Young’s wife and business partner does — yet they have managed to land international clients in part because the Sotheby’s name conveys prestige.

Iverson credits the Sotheby’s connection for getting him a Hong Kong-based client with homes around the world who was looking to add a Peninsula property to his collection.

“It’s one of the times when maybe all that stuff that they tell me at the sales conference, maybe there’s actually value there,” Iverson joked.

Those who collect global homes like trading cards have a shocking take on Bay Area real estate: It’s considered a bargain. The average home in Silicon Valley is 50% cheaper than one in Hong Kong, according to NAR data, and two-thirds the price of one in Zurich or Singapore. Plus, homes in those international locales are unlikely to come with an acre of land, as they typically do in Atherton.

Iverson’s Hong Kong buyer originally targeted Palo Alto but settled on Atherton, because even though he owns in Tokyo, London, and Hong Kong, none of those homes has a yard. The Atherton property does, and comes complete with a big palm tree.

Once his buyer saw that, Iverson said, “it was like, giddy up.”

Comfort and convenience

There’s a phrase Courtney Jung often heard from her grandparents: fang bian. It doesn’t quite translate to English, the City Real Estate agent said, but the closest word is “convenience.”

The multilayered meaning of this phrase — suitability, ease, cleanliness — runs so deep that it’s hard to explain to those who didn’t grow up with it, she said.

“That’s a term that any older Chinese person, you’ll hear them say it 1,000 times,” she said. “Even younger Chinese, it’s just a very, very strong value.”

It explains much of what Chinese buyers are looking for in Bay Area real estate, she said, and why the Peninsula in particular — with its proximity to tech jobs, good schools, and a top international airport — has such a hold on their hearts and pocketbooks.

Brand-name cities in particular bring comfort because they’re reputable and familiar — another core cultural value.

“The Chinese want something that is known, thought after, respected, and looked up to,” Jung said.

Right now, those terms don’t apply to much of San Francisco, she said, outside of premier locations like Pacific Heights and Presidio Terrace.

Chinese buyers also value single-family homes, which means San Francisco’s condo inventory is out, except for buys that are purely for investment purposes with the idea that they’ll be rented out, not lived in by the buyer. More than 70% of Chinese buyers in the U.S. this year bought detached single-family homes, according to NAR, versus 63% for foreign buyers overall.

“Of course, there are Asian people that buy condos, but for the most part, they really don’t like to pay extra for somebody else to control that money,” Jung said of the Chinese distaste for homeowner associations. “They like to have full autonomy on what they’re doing with their funds.”

That prized financial independence explains why these buyers keep returning to the Bay: It seems like a safe, well-respected bet and a good way to stash a sizable sum out of reach of possible Chinese government interference.

“It’s essentially the real estate equivalent of hiding your money in a coffee can, burying it in the backyard, or stuffing it into a mattress,” Iverson said. “Just the mattress happens to be in Palo Alto or Atherton.”