People who live, work, or shop on Oakland’s San Pablo Avenue will have to wait a little longer to see significant infrastructure changes to the busy arterial street. County officials say the bus and bike lane portions of a major corridor project will take four years longer than initially planned.

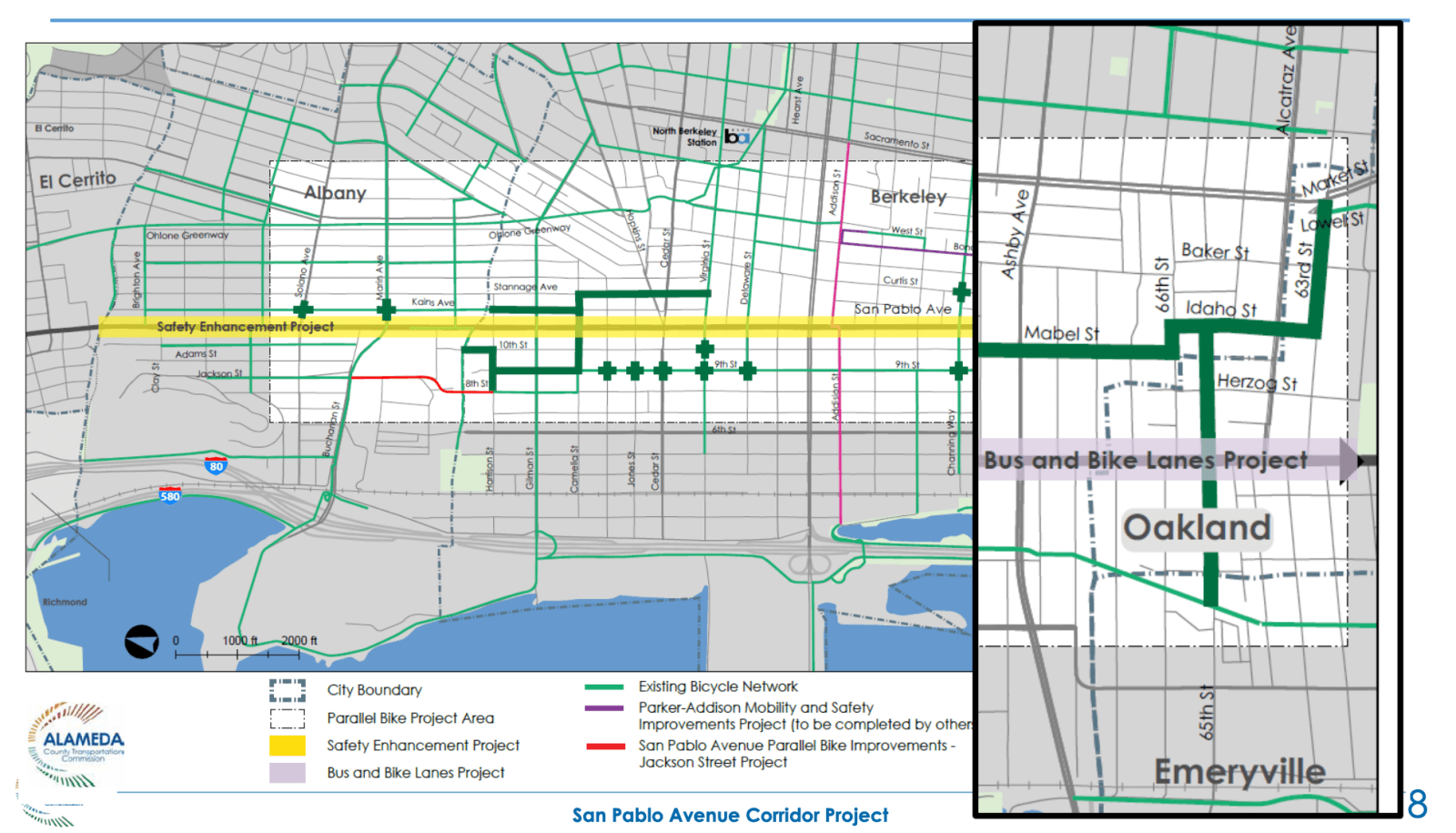

The San Pablo Avenue corridor project includes three redesigned sections of the thoroughfare that connects Oakland, Emeryville, Berkeley, and Albany:

Improved bike corridors on local roads parallel to San Pablo, Berkeley, Albany, and the edge of North Oakland

Safety enhancements, including crossings with median refuge islands and bulbouts, in Berkeley and Albany on and off of San Pablo

Protected bike lanes and a red-painted bus lane on San Pablo Avenue in Oakland, a small part of Emeryville, and a section of South Berkeley.

The element facing big delays is the bus and bike lanes in Oakland.

Staff at the Alameda County Transportation Commission, the agency that distributes state dollars to cities and manages the project, estimated in November 2022 that this part of the plan would cost $73 million and take about five years to implement, starting in 2026. But they now say it will take longer and cost more. The revised plan is for the bus and bike lane project to break ground in 2030, at a total cost of $250 million.

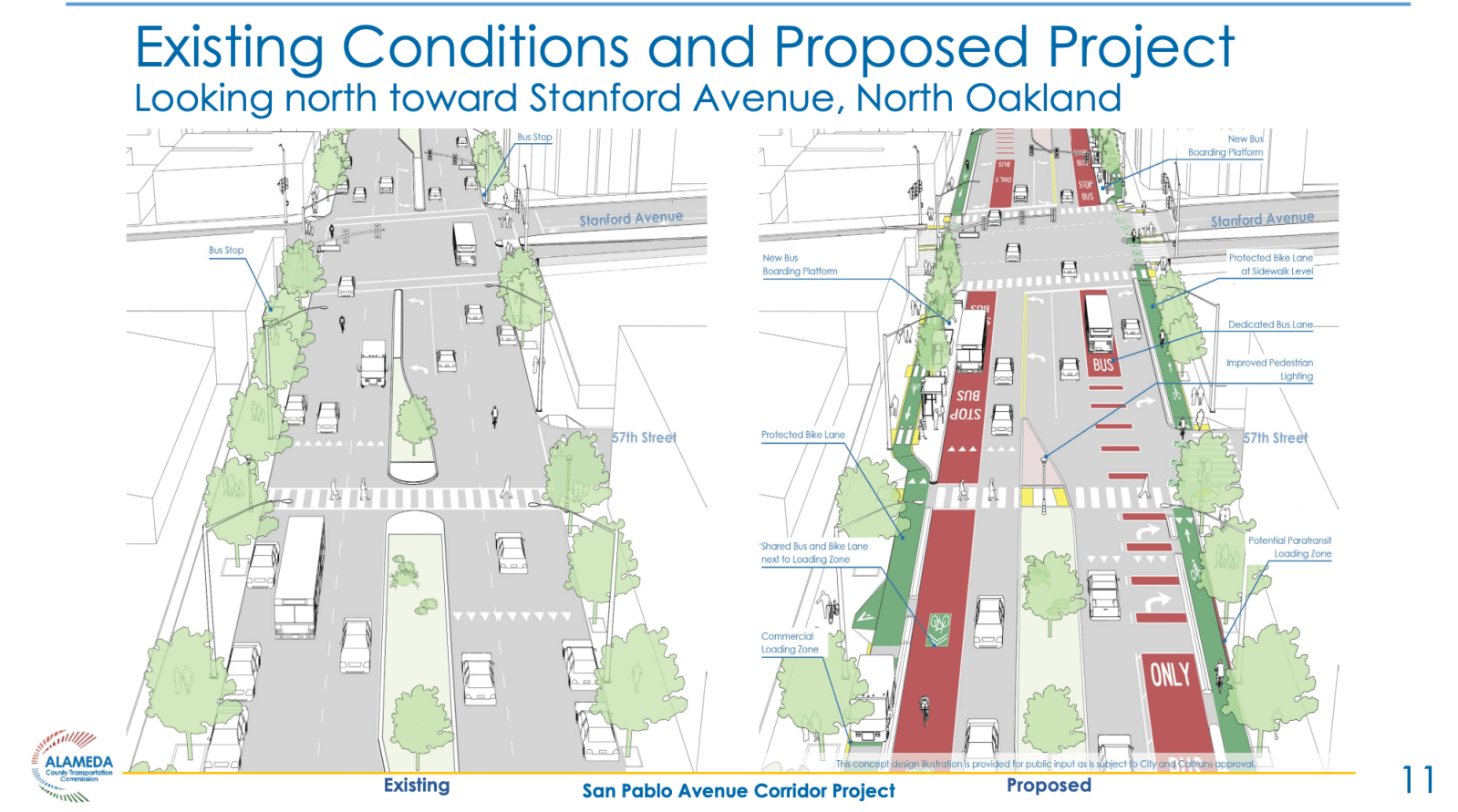

Colin Dentel-Post, the ACTC assistant director of planning, and Matt Bomberg, a staff transportation engineer, told the Infrastructure Committee of Oakland’s Bicycle and Pedestrian Advisory Commission on November 6 that the the bike and bus lane part of the project has changed from a quick-build with “a lot of paint,” “some posts,” and “maybe some concrete curbs” to a full-blown capital project with more durable materials and “intensive treatments” that will lead to “a more robust, safer, long-term project.”

A safer project is a more expensive one

A slide from s Alameda County Transportation Commission presentation shows the current proposed treatment of San Pablo Avenue in Oakland. Credit: ACTC

A slide from s Alameda County Transportation Commission presentation shows the current proposed treatment of San Pablo Avenue in Oakland. Credit: ACTC

The project ballooned, the engineers said, after they consulted with city officials and residents from the various cities involved in the bus and bike lane corridor project, who all shared their own must-haves. They heard loud and clear that stakeholders wanted more substantial infrastructure to make the road safer and easier to travel on.

Agencies didn’t want buses and bikes sharing space, communities didn’t want mixing zones, disability advocates didn’t want bike-pedestrian mixing, businesses needed certain loading accommodations, more lighting needed on side streets, bus lane intrusion countermeasures were needed, and Caltrans needed a more rigorous environmental and geometric approval process, Dentel-Post said at the meeting, which also included staff from Oakland’s transportation department.

Asked whether the project could experience further delays and further cost overruns, the ACTC staff said their new time and cost estimates were conservative, though “no one can predict the future, and certainly projects do experience delays,” Bomberg said.

For advocates who showed up for the BPAC infrastructure committee meeting, it was a frustrating development.

“Between the neighbors I talk to, there’s a parent who crosses the street daily with kids, a person with a disability who can’t drive anymore who has to be on foot there, and someone who’s been hit by a car,” an East Bay resident said at the meeting. “We just want to see it happen. We want you guys to feel the urgency and get creative. We want to experience this before more people get hurt or killed in this corridor.”

Robert Prinz, Bike East Bay’s advocacy director, led the meeting as the committee’s co-chair. He expressed dismay that ACTC had not communicated the timeline and cost issues earlier.

Prinz told The Oaklandside he was shocked by the agency’s estimate that construction on the bike and bus lanes in Oakland wouldn’t begin until 2030 and asked about what factors drove the higher price. He said that a source told him that part of the higher price was due to Caltrans’ insisting on narrowing the San Pablo Avenue sidewalks in order to create wider travel lanes, but he said ACTC and Caltrans haven’t confirmed that. The Oaklandside reached out to both agencies about this claim and have not yet heard back.

“The public communications about the project have been very minimal,” Prinz told us.

The redesign of most of San Pablo Avenue — the stretch from Oakland to Richmond — has been in the works for a decade. It’s been focused on making the road safer and more accessible in anticipation of an influx of property and business development. Data shows that the avenue’s current design is not ideal. ACTC has said that more people got into collisions on San Pablo than on any other central traffic corridor in the county, with pedestrians and cyclists accounting for 64% of injuries or deaths.

According to Dentel-Post and Bomberg, the two other parts of the San Pablo project — the parallel streets and safety enhancements, mostly in Berkeley and Albany — are close to being fully designed. The safety enhancement design is 95% complete and has been cleared by environmental review, and the project will open to bids from construction companies by the summer of 2026. The bike corridor designs are 100% complete, with construction contracts going out to bid this spring.

Lessons from International’s ‘disastrous’ bus lane

An AC Transit bus and two cars collided in March 2024 at the intersection of International Boulevard and 54th Avenue after one of the cars was speeding. Credit: Jose Fermoso/The Oaklandside Credit: Oakland Fire Department

An AC Transit bus and two cars collided in March 2024 at the intersection of International Boulevard and 54th Avenue after one of the cars was speeding. Credit: Jose Fermoso/The Oaklandside Credit: Oakland Fire Department

Most of the key challenges the design team has faced over the last two years in planning the three-part project have been resolved, the engineers said, but some substantial changes were required along the way.

For example, for the parallel streets plan in Berkeley, the team chose low-profile, mountable traffic circles that could accommodate large trucks, like those of a fire truck, in an emergency. For the bike and bus lane project, deciding whether to add the dedicated lane next to the sidewalk or in the middle of San Pablo meant learning lessons from the International Boulevard bus-rapid-transit project.

That project, completed in 2020, faced serious problems, as impatient drivers used the bus-only lane to bypass slow traffic. This has put bus riders, including children and seniors, in harm’s way as they cross the boulevard. In the last two years, OakDOT tried to solve these problems by adding bollards to block drivers from entering the bus lane and are in the process of adding a speed hump to slow down those who continue to do it.

ACTC engineers said they were seeking to avoid this issue on San Pablo Avenue by placing the bus lane next to the sidewalk. They said the bike lanes will also be protected in some sections by hardened separators or by being elevated to the same height as the sidewalks.

“Oakland does have side-running bus lanes on East 12th Street,” Prinz noted. “The East 12th Street ones haven’t been perfect, but they haven’t been as disastrous as the International ones were.”

Removing parking spaces to make room for buses, cyclists

Another ACTC slide of the San Pablo Avenue project shows how the corridor will be redesigned as it moves through Oakland and into Emeryville, Berkeley, and Albany. Credit: ACTC

Another ACTC slide of the San Pablo Avenue project shows how the corridor will be redesigned as it moves through Oakland and into Emeryville, Berkeley, and Albany. Credit: ACTC

To accommodate the bike and bus lanes along the Oakland stretch of San Pablo Avenue, ACTC staff said they expect to remove most vehicle parking — a key provision International Avenue businesses fought against in the late 2010s and won. However, that still didn’t prevent some businesses on International from experiencing displacement, partly due to the length of the roadway construction.

ACTC staff said they went door-to-door along San Pablo to assess businesses’ needs so they could try to accommodate them.

“We’re trying to do the best we can on side streets to figure out whether parking meters would be helpful, whether they would discourage customers, whether loading zones are needed, and whether customers are low income,” Dentel-Post said. “Will it work perfectly? Definitely not.”

Bomberg noted that one of ACTC’s unsexy but essential tasks was figuring out how to work up project specifications for projects that span multiple jurisdictions, each with its own restrictions.

“Finding a way to harmonize all those tasks so that the contractor during construction isn’t having to use different concrete mix designs at two adjacent intersections, it’s been a significant area of work,” he said.

One road redesign that will benefit from this complicated development work is 65th Street.

Stretching from the edge of Emeryville, near its popular Greenway, to parts of Berkeley and North Oakland, this street is being redesigned as a critical connector between the San Pablo Avenue project and the I-80/Ashby Avenue Interchange project, the ACTC engineers told the BPAC committee. The latter involves building a bridge over Interstate 80 so people can walk or bike all the way from Oakland to the Bay Trail. ACTC staff told the BPAC committee that they had added speed humps and parking-protected bike lanes to their 65th Street plans.

“65th Street is gonna get really important,” Bomberg said.

“*” indicates required fields