San Francisco health and redevelopment officials waited nearly a month to alert the community about a suspected plutonium detection at the Hunters Point Shipyard, even as they criticized the U.S. Navy for keeping the discovery under wraps.

The city’s decision to elevate the urgency of the finding set off a public outcry at the Navy’s expense. Still, it is unclear how much health danger the incident posed. Navy officials cautioned that the detection could be a false positive, and one radiation expert said the city’s reaction “exaggerated” its scientific significance, resurfacing doubts about the future of a massive and complex real estate project.

“The levels are very small and the health impact negligible,” said Kai Vetter, a professor of nuclear engineering at the University of California, Berkeley, who has studied pollution at the shipyard. “From the point of communications and perception, it is quite damaging.”

The dispute came to a head in a sharply worded Oct. 30 letter from San Francisco’s Department of Public Health, which charged that the Navy failed to promptly disclose a November 2024 plutonium detection at the long-contaminated bayfront property. The Navy did not inform the city until about 11 months after the sample was retrieved, though the Navy said it took a long time to discover the issue and sort out whether it had found anything at at all.

“Such a delay,” wrote Dr. Susan Philip, the city’s health officer, “undermines our ability to safeguard public health and maintain transparency.”

Her letter resulted in Navy officials issuing a seldom-seen public apology at a Nov. 17 community meeting. It also prompted admonishment from U.S. Rep. Nancy Pelosi, one of the most reliable supporters of the shipyard’s development plans. “The continued cadence of misfires in communication and delays with the completion of the cleanup further erode the public trust in the Navy’s ability to complete this long awaited clean up and redevelopment,” Pelosi told Navy Secretary John Phelan in a Nov. 24 letter.

But emails obtained by the San Francisco Public Press show city officials knew about the finding since at least Oct. 2, and chose to keep both the public and Mayor Daniel Lurie in the dark until Philip’s Oct. 30 letter appeared in selected media outlets.

In a Nov. 7 response to Philip, Navy officials wrote that the result was an anomaly that “could not be reproduced” by later tests.

The plutonium concentration initially reported by a contractor — about 8.16 quadrillionths of a microcurie per milliliter of air — represents a tiny amount of radioactivity. Independent scientists said the health effects of the element, if actually detected, would be extremely small, equivalent to about two chest x-rays if inhaled continuously for a year.

As environmental cleanup continues at the shipyard, the Navy continuously monitors several locations for airborne contaminants including radioactive materials. Credit: U.S. Navy photo

As environmental cleanup continues at the shipyard, the Navy continuously monitors several locations for airborne contaminants including radioactive materials. Credit: U.S. Navy photo

But the affair reignited long-standing community mistrust about the $1.1 billion cleanup of the former naval base, once the site of ships contaminated by Pacific atomic bomb tests and later a major radiation laboratory that studied materials, military readiness and human and animal biological effects.

Several neighborhood environmental and health watchdogs decried what they called another sign of the military’s long-running neglect of its pollution legacy, while one national group blamed the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency for this “latest fiasco.”

The episode also added to the public relations headache for the decades-long effort to build more than 10,000 units of housing at the 450-acre former base. Pelosi said ultimate responsibility for the real estate project’s needed turnaround belonged to the military: “That effort is entirely reliant on the Navy’s ongoing, frequent dialogue with total transparency.”

The Department of Public Health accepted federal agencies’ analysis that no hazard existed, while also heaping skepticism on the Navy. “Based on the information currently provided by the Navy, and preliminary assessment from the EPA, no immediate action is required from a public health safety standpoint,” the local agency said in response to emailed questions.

“The Navy’s conclusions cannot be accepted at face value,” the statement continued. “We must review, with our regulatory partners, the information to ensure it is complete, accurate, and protective of community health.”

Asked to explain the timing of its announcement, the health department emphasized the necessity of transparency: “When information about possible contamination is delayed for nearly a year, we have to speak up,” adding, “The department informed the community because transparency builds trust — silence does not.”

Planned meeting canceled abruptly

The first local official to learn of the plutonium question appears to have been Dr. Veronica Hunnicutt, chair of the Hunters Point Citizens Advisory Committee, a panel charged with communication with local stakeholders. Michael Pound, the Navy’s environmental coordinator, first mentioned it to her on Sept. 22, according to an email chain obtained by the Public Press.

After Hunnicutt contacted Pound with further questions, and expressed concerns that incomplete information could lead to public confusion, on Oct. 2 Pound forwarded her email to officials at the Department of Public Health and the city Office of Community Investment and Infrastructure, which oversees residential and commercial redevelopment at the former shipyard.

In his response, Pound noted that he mentioned “the Pu exceedance” — a reference to the possible detection of highly radioactive and long-lived plutonium-239 — to Lila Hussein, the senior project manager for the shipyard’s redevelopment, sometime that day.

Aware that the story needed to get out, Pound asked for Hunnicutt’s “recommendations for sharing the information with the public.”

Hunnicutt urged restraint, warning against triggering panic over what might be a “false positive,” writing, “That’s why it’s very important to avoid any hasty announcement.”

On Nov. 17, the Navy convened neighbors to discuss their concerns about the plutonium detection, calling it a false positive reading but apologizing for delaying communication about it. Credit: Chris Roberts / San Francisco Public Press

On Nov. 17, the Navy convened neighbors to discuss their concerns about the plutonium detection, calling it a false positive reading but apologizing for delaying communication about it. Credit: Chris Roberts / San Francisco Public Press

At a recent affordable housing ribbon-cutting at the shipyard, Hunnicutt declined to comment for this story.

To address other agencies’ questions, the Navy scheduled a meeting with local, state and federal interests for Oct. 29 to coordinate disclosure, a Navy spokesperson told the Public Press.

But at the last minute, the Navy said, the Department of Public Health canceled that meeting. Instead, department staff sent two letters, dated Oct. 30. The first went to the Navy. The second letter, addressed only to Hunnicutt’s committee and another community group, stated: “Full transparency with our communities and the Department of Public Health is critical, and we share your deep concerns regarding the 11-month delay in communication from the Navy.”

Lurie said he was out of the loop for the four weeks that officials were deciding what to do. “We got the news when we all got it, about a week ago,” the mayor told the Public Press on Nov. 7 at the ribbon-cutting event.

Cold War legacy

The presence of plutonium, the key ingredient in nuclear weapons, should not surprise anyone familiar with the shipyard’s history.

As the Public Press reported last year in its investigative series “Exposed: The Human Radiation Experiments at Hunters Point,” airborne plutonium was detected around the docks as early as 1947. The source was target vessels towed back to San Francisco after they were blasted in above-ground atomic weapons tests on Pacific islands early in the Cold War. Hundreds of workers were ordered to “clean” the ships with hand tools and sandblasters — which only served to spread the contamination.

The Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory, the research unit that directed this work, exposed at least 1,073 service members, dockworkers and scientists to radiation in occupational and medical tests that pushed up against the era’s emerging ethical standards, according to fragmented historical records from the National Archives, science journals and other databases.

Researchers reported to the Navy that plutonium and other hazardous material could have migrated to the nearby majority-Black neighborhood on the wind, yet no evidence could be found that the Navy ever warned local residents. The military never studied the shipyard’s effects on local health outcomes, which have been found to be some of the worst in the Bay Area.

The redevelopment project has for decades been plagued by seemingly endless controversy, including supervisors at Navy contractor Tetra Tech EC being sentenced to prison in 2018 for having submitted faked testing results on soil samples in the cleanup zone. That set the project back years and prompted retesting that is still ongoing.

In her email to the Navy’s Pound, Hunnicutt also referenced detection in 2021 of strontium-90, a radioactive isotope. That led to accusations that the Navy was covering up the finding after it reanalyzed samples using a different method that detected no strontium. “That case was botched because it created an unnecessary anxiety in the community, and to this day the stakeholders still talk about it,” Hunnicutt wrote.

This year’s plutonium affair is reigniting these fears at a key moment. Next year the Navy wants to start demolishing shipyard buildings, some of which could contain traces of radioactive substances. After apologizing to community members at the Nov. 17 meeting for sitting on the plutonium finding for nearly a year, the Navy also found itself fending off rumors that it planned to take down the buildings with dynamite.

Ambiguous test result

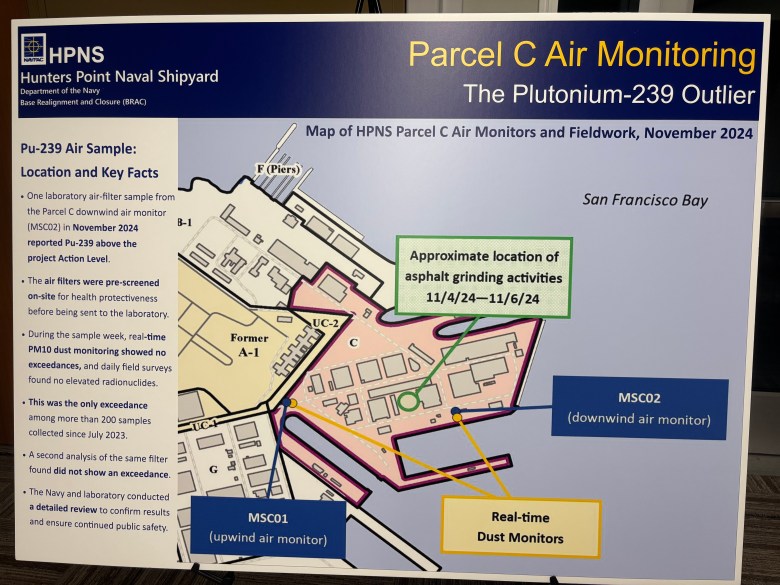

The Navy claims it was first informed last March that a contractor cutting through an asphalt cover the previous November to retest areas tainted by the TetraTech EC fraud scandal discovered plutonium-239 in an air-monitoring station. Although the reported concentration was minuscule, it exceeded the site-specific “action level” that triggers review.

The Navy halted work while sending the sample for retesting and said follow-up analysis failed to detect any plutonium.

“These inconsistencies called into question the validity of the result,” wrote Anthony Megliola, director of the Navy’s Base Realignment and Closure office, in the Nov. 7 letter. “Given these facts, we believed it was prudent to work with our experts to attempt to validate the authenticity of the result before communicating it publicly.”

Navy officials told residents at the Nov. 17 community meeting that only one air monitoring station picked up a trace of plutonium-239, and a re-analysis of the sample came up negative for the isotope. Credit: Chris Roberts / San Francisco Public Press

Navy officials told residents at the Nov. 17 community meeting that only one air monitoring station picked up a trace of plutonium-239, and a re-analysis of the sample came up negative for the isotope. Credit: Chris Roberts / San Francisco Public Press

Sometime after the Navy found out, it published quarterly air-monitoring reports on its website that claimed no plutonium detection. That “was mistakenly uploaded” and later corrected, a Navy spokesperson told the Los Angeles Times.

The Navy has not explained why it did not alert the U.S. EPA until Oct. 23, weeks after it told the city, said Michael Collins, an EPA representative.

To be sure, the health effects of the plutonium detected, if it even existed, would probably have been relatively insignificant, independent experts said.

“Plutonium is bad news and raises many flags,” said Tom McKone, a professor emeritus of environmental health sciences at UC Berkeley.

He emphasized that the shipyard’s action level “is actually very low” — so conservative that it is not a good measure of risk. Someone breathing the initially reported level continuously for a year, McKone said, would receive about the dose of two chest x-rays — roughly 3% of the annual dose from all sources for an average American.

If the Navy knew the risk was tiny, he asked, why would it take so long to share that information? Its behavior over the 11-month timeline only served to elevate public suspicions and spur the ongoing interagency blame. “I can’t imagine that they need a year to confirm their measurements and decide what action to take,” he said.

Related