This was supposed to be San Francisco’s year of the bike lane. After more than two years of discussion and much fanfare, the city’s streets and transit agency in March unveiled the Biking and Rolling Plan, a major update of SF’s bike network, meant to connect more neighborhoods and build in more street safety.

But while approving the plan, transit officials backpedaled on expectations. It turned out to be more like an outline where future bike lanes could go, and specific proposals — and funding — were still to come.

SF Bicycle Coalition marketing and communications director Krissa Courvas says the approval has committed the city to “making progress towards a safe, interconnected citywide network that benefits all of the city.”

But the lack of detail was a letdown for people expecting something more robust. In the face of political heat over road changes, the rest of the year has seemed to be a much slower roll for bike projects.

Here’s the scorecard: two new bike projects opened in 2025. One was a controversial compromise: the side-running lanes that replaced the ill-fated Valencia Street center lanes. The other completed project is near the San Francisco Zoo, along Sloat Boulevard.

Another existing lane, along a roughly half-mile stretch of Alemany Boulevard, received added protection. But other projects that already have funding and approval have been slow to materialize.

When SFMTA first started ramping up bike lane work through the Quick Build program six years ago, safety projects were easier to approve and install. But in recent years, SFMTA has hit a budget crunch and another obstacle — what SFMTA Livable Streets director Kimberly Leung calls “community readiness.” In other words, some neighborhoods were more ready than others. Chinatown, for example, flat-out refused a bike lane plan in 2024.

A new two-way protected bikeway on the south side of Sloat Boulevard includes newly painted crosswalks to warn pedestrians about two-wheeled traffic. (Photos: Kristi Coale)

A new two-way protected bikeway on the south side of Sloat Boulevard includes newly painted crosswalks to warn pedestrians about two-wheeled traffic. (Photos: Kristi Coale)

After the city used the pandemic to rethink many roads, including Golden Gate Park’s JFK Drive, the Great Highway, and two dozen neighborhood “slow” streets, a backlash has been building. Valencia Street was a big part of it.

Now, when drivers feel constrained, or merchants and neighbors feel threatened, plans to increase bike and pedestrian safety have been watered down (West Portal and Lake Street) or discarded entirely (Chinatown). In the case of the Great Highway, now Sunset Dunes Park, the backlash spurred the recall of Sup. Joel Engardio.

In coming years, SF’s recently approved rezoning plan could bring tens of thousands of new homes, mostly to western neighborhoods. As SFMTA Biking and Rolling Plan project manager Christy Osario noted at a Nov. 2024 meeting, “We don’t have the capacity for that many cars.”

Biking is an alternative, and electric bikes will give even more people a way to get around the city car-free. But physical ability is only one factor for bike use. Riders also need to feel safe, which requires separation from cars. Since the 2019 start of quick-build installation of bike lanes, traffic incidents involving cyclists have dropped by 25 percent.

As 2025 wraps up, here’s a recap of the city’s progress — and what the next few years might bring.

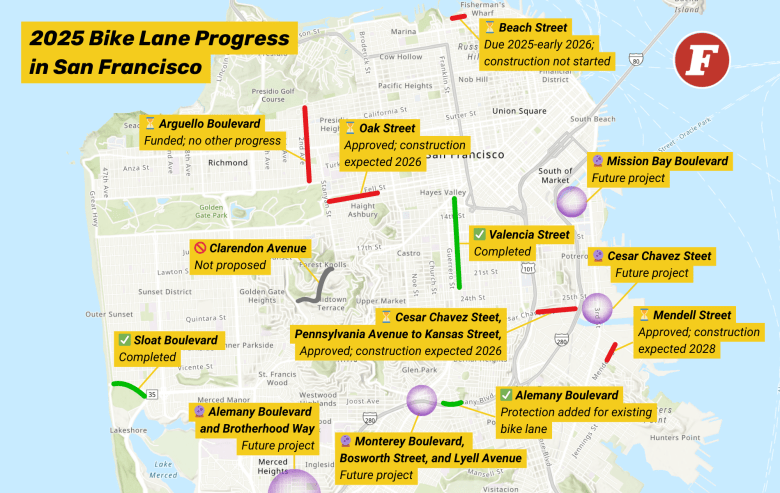

Bike lanes across SF are in various states of flux. Some have funding but no plans; others have a long road to approval. (SF Open Data, The Frisc)

Bike lanes across SF are in various states of flux. Some have funding but no plans; others have a long road to approval. (SF Open Data, The Frisc)

2025’s tally

Aside from Valencia, only one bike lane was completed this year: a two-way protected lane on the south side of Sloat Boulevard between Ocean Beach (and Sunset Dunes Park) and Skyline Boulevard. Both east and westbound lanes are separated from cars by Muni passenger islands in some spots and buffer zones with plastic posts in others. Newly painted crosswalks also warn pedestrians — “Look” — about the new two-wheeled cross-traffic.

Something is happening at Beach Street — but if it’s a bike lane, only a very small stretch is underway. (Photo: Kristi Coale)

Something is happening at Beach Street — but if it’s a bike lane, only a very small stretch is underway. (Photo: Kristi Coale)

Another project due this year might not make the deadline. On Beach Street between Polk Street to the Embarcadero — one block south of Fisherman’s Wharf — a two-way protected lane will connect the Marina and Fort Mason to the rest of the Embarcadero. When The Frisc visited the street last week, there was no sign that construction had begun, except perhaps on one half-block stretch.

When asked about other recently completed bike lanes, SFMTA noted Lake Merced Boulevard and 17th Street. Both were finished in the first half of 2024.

Almost but not quite

This year, bike advocates and neighborhood residents were hoping to see a protected bike lane on Clarendon Avenue, which cuts across the flank of Mount Sutro. The SFMTA board approved pedestrian safety improvements last month, but there was no bike lane included.

Livable Cities senior policy manager Tom Radulovich said it should have been a “no brainer,” given that there are few driveways and cross streets and no loss of parking spaces.

But SFMTA’s Leung said Clarendon had too many issues. It’s steep. It has a school dropoff zone. It also has a hard center median, making it impossible for fire trucks to use the middle of the road to pass in emergencies. Radulovich saw it partly as a sign of Mayor Daniel Lurie not being “a big supporter of sustainable transportation.”

He pointed to an SF ordinance that requires the city to accommodate all modes of transportation when a street is rebuilt or — as with the Clarendon pedestrian changes — undergoes a major physical improvement.

“The city wouldn’t consider any alternatives with a bike lane,” Radulovich told The Frisc.

Coming… eventually?

Meanwhile, two other bike lane projects are fully funded and approved but still await installation.

The first is Oak Street, along the Panhandle, which got funding in 2021 and full approval eight months ago. But only a tiny fragment has been completed. In a November update, SFMTA said crews would begin work on another small piece in mid-December But the main construction will come in the spring, after Oak is repaved from Stanyan Street to Van Ness Boulevard.

Only a small fragment of Oak Street’s future bike lane — which will closely mirror Fell Street on the other side of the Panhandle — has begun. The project was approved eight months ago. (Photo: Kristi Coale)

Only a small fragment of Oak Street’s future bike lane — which will closely mirror Fell Street on the other side of the Panhandle — has begun. The project was approved eight months ago. (Photo: Kristi Coale)

Another funded project just won approval. On Dec. 2, the SFMTA board of directors approved the Bayview Community Pathway Project after a month’s delay. The proposal includes a protected bikeway on a largely industrial part of Mendell Street. Construction is slated to start in 2028.

More work is coming to “the Hairball,” where Highway 101 connects to several streets on the east side of the city. Board approval was due this year. (Photo: Lisa Plachy)

More work is coming to “the Hairball,” where Highway 101 connects to several streets on the east side of the city. Board approval was due this year. (Photo: Lisa Plachy)

The tangle of streets and Highway 101 known as the Hairball has long been a target for safety improvements. They’re getting closer. The project just went through a first engineering phase but needs SFMTA board approval, which was supposed to come this year. It will run along Cesar Chavez Street east of 101. Construction is due to start in 2026. When finished, it should connect riders to the Evans Avenue bike lane and the future Hairball Intersection Improvement Project to give safer passage for pedestrians, cyclists, and other wheeled users.

Perhaps the most disappointing delay for bikers is Arguello Boulevard. Inside the Presidio, champion cyclist Ethan Boyes was hit and killed there in 2023. The Presidio Trust has made upgrades. But on the 1.1 miles of Arguello within SF city limits, there’s been no bike-related changes to the unprotected bike lanes, despite heavy use by cyclists, a recent horrific collision, and $1.4 million in funding that’s been available for years.

On the drawing board

Bike lane critics sometimes say that with SFMTA’s fiscal crisis, the money should instead go to public transit.

But the funding isn’t easy to shift. Street work like bike lanes and pedestrian safety have dedicated revenue streams through state grant programs and voter-approved measures, including a 2019 tax on ride hail that has generated $34.8 million for street safety projects.

Transit-related taxes are collected and disbursed by the SF County Transit Authority, a parallel body to SFMTA whose members are the city’s 11 supervisors.

To get the funds, SFMTA presents projects to SFCTA for approval and must report on its progress every quarter.

Among the projects approved last year, garnering $3.8 million in funds, are four that involve protected bike ways.

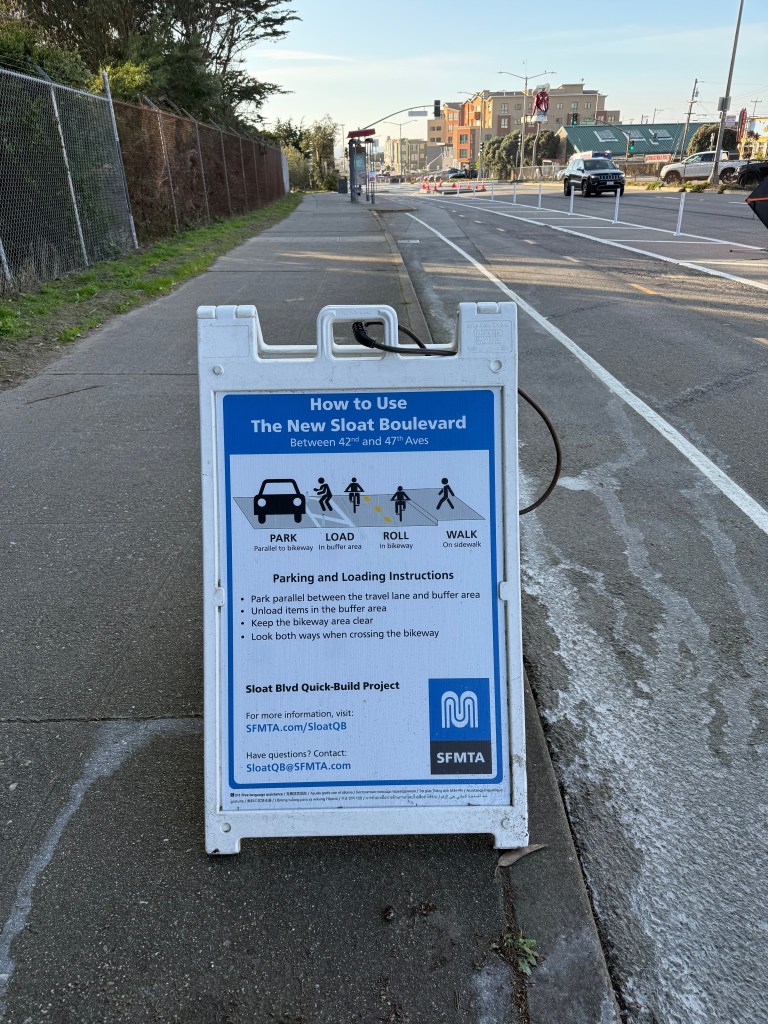

Don’t park here: New instructions for the Sloat Blvd. bike lane. (Photo: Kristi Coale)

Don’t park here: New instructions for the Sloat Blvd. bike lane. (Photo: Kristi Coale)

Cesar Chavez appears again — this time to connect Bernal Heights and the Mission with separated bike lanes to the waterfront, where thousands more residents will soon move into the nascent Pier 70 and Power Plant developments.

In Glen Park, three neighborhood streets could get new bike lanes or improvements. The southwest corner of the city could get new lanes along Brotherhood Way, Alemany, and Sagamore Street. Mission Bay could get separated bikeways along with other safety upgrades in anticipation of the neighborhood’s new K-8 school.

For now these are just fledgling ideas. Before they get to the SFMTA board for approval, they need real designs then go through public outreach. But for SF bike projects these days, outreach often turns into outcry.

More from The Frisc…