Since its opening in 2005, the signature image of the Museum of the African Diaspora has been photographer Chester Higgins’s “The Girl from Ghana,” a three-story photomosaic covering the wall along the museum’s main staircase.

From across the street, one can see a young girl in a headwrap and a matching dress. Climbing the stairs inside the museum, one sees more than 3,000 stamp-sized photographs from professional and amateur contributors around the world, who responded to a call for images of the African diaspora. The mosaic shatters the notion of a Black monolith by presenting the variety and specificity of the African diasporic people: out of one, many. A wall text about the work reads, “This duality – intimate and global, personal and shared – embodied MoAD’s founding mission.”

MoAD, which shares the first three stories of the St. Regis Hotel, is capping two months of 20th anniversary events with a public celebration Saturday, December 13, from 2 p.m. to 4:30 p.m. and two exhibitions, “Continuum: MoAD Over Time” and “UNBOUND: Art, Blackness and the Universe.” The shows exemplify where MoAD has been and where it is headed.

Throughout its initial decade, MoAD told stories of the African diaspora from the first humans to the present, mainly through permanent educational installations. This is the MoAD you see in filmmaker Barry Jenkins’s indie feature “Medicine for Melancholy,” an institution leaning more towards anthropology, history, travails and accomplishments. But when Linda Harrison came on as executive director in 2013, she shifted the museum to center contemporary Black artists. Without changing its name, MoAD came into its own as essentially the Museum of the African Art Diaspora.

Monetta White, CEO of MoAD, Photo by Brandon Ruffin

Monetta White, CEO of MoAD, Photo by Brandon Ruffin

Consistently, through Harrison’s tenure and, since 2019, under Monetta White’s leadership as chief executive officer, MoAD has been delivering on the ambition, innovation and quality of its exhibitions and programming.

“The art we champion reveals the world as it really is: interconnected and complex and beautifully diverse,” said White.

Changing the museum from the kind of place where you might see a Maya Angelou quotation on the wall and hear an actor reading a slave narrative to a place where you might encounter abstract paintings and multimedia installations, meant developing new programming.

Elizabeth Gessel, MoAD’s curator of public and academic engagement, started at MoAD as a volunteer in 2009 and has produced more than a thousand MoAD public events. “I think there’s an intimidation factor for people coming into a contemporary art museum, and knowing how to interact with the work or what they’re supposed to get out of it or how to do that,” she said. “And so for me, doing the public programming provides different entry points for folks to really become comfortable with and engage with the exhibitions through an avenue that they are intrigued or excited by.”

That might mean movies, like inviting film curator Cornelius Moore to present a film series linked to exhibitions, or music, like the project she did with Bay Area jazz treasure John Santos on the African roots in Latin jazz.

Or food. Harrison hired cookbook author Bryant Terry, MoAD’s first chef in residence, and gave him rein to connect food, culture and activism. Gessel worked closely with Terry on the Black Food Summit, food writer panels, and school and community events, including the first Diaspora Dinner.

As MoAD enters its third decade, White says it is ready to engage on a global stage. “Telling our stories, making sure that we’re seen and heard and the importance of really being at the core of the conversation. We shape contemporary art and I want the world to know it.”

To that end, in 2023 MoAD hired Key Jo Lee, its first full-time staff curator.

“I’m the inaugural chief of curatorial affairs. Monetta created this position,” Lee said.

Lee says that with expanded wall text and question prompts, she hopes to “bring people into the conversation, and at the cutting edge of what’s happening in contemporary, global Black art. MoAD has done early exhibitions for some really wonderful artists that are now becoming household names, like Amako Bowafo received his first U.S. solo exhibition here.”

She is building a curatorial team. “We will have a joint assistant curator with SFMOMA, the deputy chief of curatorial affairs, the curatorial assistant and the manager of exhibitions, so we will go from a team of two to more than doubling in the next three months.”

Lee marveled at how much MoAD has been able to accomplish. “That a museum that started with a staff of six is able to put on almost 2,000 programs is wild.”

Like many museums, MoAD lost significant funding when the federal government rescinded arts grants and ended support for museums and libraries. Early on, White was concerned about losing MoAD in the Classroom and the Emerging Artists Program. But she says MoAD’s community has stepped up to save those projects.

Sam Vernon, Impasse of Desires:

Sam Vernon, Impasse of Desires:

Sanctuary, 2025.

Courtesy of the Artist and Museum

of the African Diaspora (MoAD)

The centerpiece of “Continuum: MoAD Over Time,” a new Sam Vernon work, invites a fresh consideration of Chester Higgins’s grand mosaic. In “Impasse of Desires: Sanctuary” (2025) Vernon situates a smaller black and white print of “The Girl from Ghana” in a recess in a gallery wall and frames it with a new photomosaic featuring Higgins’s original photo “The Girl from Tamale (Ghana, 1973)”, graffiti, newspaper stories and protest posters. But Vernon’s piece also flows from her own “Impasse of Desire,” the name of her 2020 MoAD solo show and site-specific full-color photomosaic responding to the lack of queer and gender-nonconforming representation in “The Girl from Ghana.”

“Continuum” also features the work of San Franciscans Cheryl Derricotte and Ramekon O’Arwisters, two veterans of the Emerging Artists Program Harrison launched in 2010. Each EAP artist gets a three-month solo show at MoAD.

Cheryl Derricotte. Photo by Jeffrey Foote

Cheryl Derricotte. Photo by Jeffrey Foote

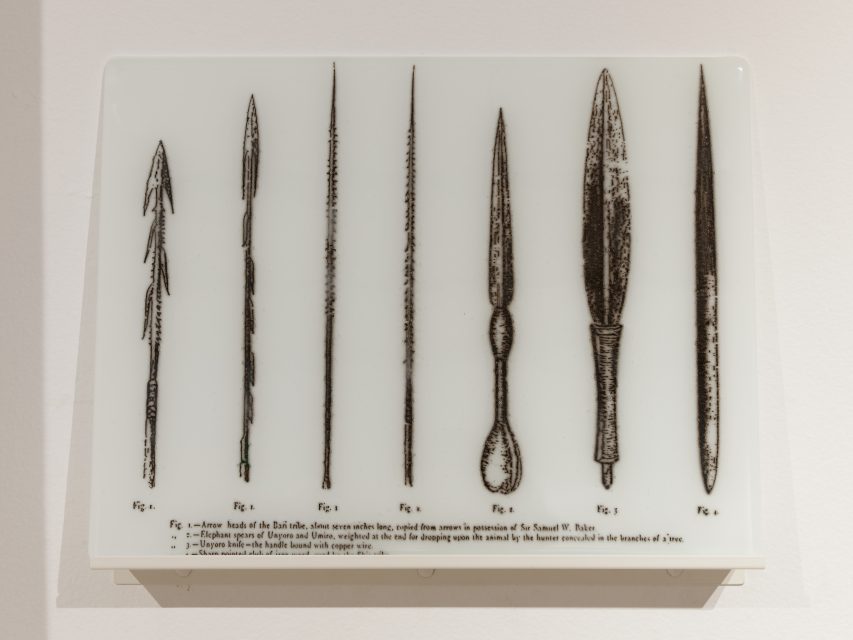

Cheryl Derricotte recreated “Tools of Resistance,” (2015/2025 handcut glass and mixed media) for “Continuum: MoAD Over Time.”

Cheryl Derricotte recreated “Tools of Resistance,” (2015/2025 handcut glass and mixed media) for “Continuum: MoAD Over Time.”

Derricotte, one of the inaugural emerging artists, needed to recreate a piece from her residency when she was asked to be in “Continuum.”

“I had to,” she said, shaking with laughter. “I had sold everything I had in that show.”

Derricotte, who was finishing her MFA at the time, said, “It was a huge thing to have happen in my life, that not only was it my first solo show, it was my first solo show at a major museum. In terms of my career, it was the immediate resume maker.”

Noting how MoAD prizes connecting people and artists, Gessel said, “People get to actually see living artists in person talking about their work, which is a pretty exciting and rare opportunity and we do it a lot.”

Like the JoeSam. exhibition, which closed in March 2024 with a conversation with the artist, two of his longtime local artist friends, Dewey Crumpler and Oliver Lee Jackson, and curator Erin Jenoa Gilbert. An endlessly inventive multimedia artist, JoeSam., who was Zooming from his home in Connecticut, lived and worked in San Francisco from 1975 to 2015. He died at 85, just three months after the MoAD exhibition, his first museum show in San Francisco. Talking about the time they all went to Paris for a Black artists’ summit and how Faith Ringgold got mad because someone wouldn’t let her into a party, they offered a fascinating glimpse into the Bay Area’s Black artist history.

Or Toyin Ojih Odutola’s artist talk for her solo show “A Matter of Fact” in 2016. The next day, she was flying to her new home in New York City and within a year she would be a bona fide ART STAR. But that night was also a sort of farewell party as the Nigerian-American artist, who had recently earned an MFA at California College of the Arts, mingled and took pictures with friends and old classmates and professors. Within months, she had her first New York solo show at the Whitney Museum.

“I’m so grateful to be working at MoAD because it showed me how the Bay Area has been a perpetual incubator of Black brilliance,” said Lee.”But it is also a world-class global arts institution. And that’s what we’re going to continue to show off.”

MoAD admission is $15 for adults, $7 for teens, elders and teachers and free for children 5-12, MoAD members and active military members. Most events are included with admission.