In the Curator’s Words is an occasional series that takes a critical look at current exhibitions through the eyes of curators.

Eight months ago, when the Union-Tribune first launched the In the Curator’s Words series, Derrick Cartwright, in a thoughtful and straightforward manner, talked about the significance of juxtaposing Albert Bierstadt’s 1864 oil-on-canvas painting “Cho-looke, the Yosemite Fall” with First Nation Canadian artist Kent Monkman’s 2012 work “The Fourth World.”

Cartwright, director of curatorial affairs for the Timken Museum of Art and a professor at the University of San Diego, has a way of demystifying art and making it more accessible.

Today, Cartwright is back, this time to talk about a stunning new exhibition at the Timken focused on 16th-century portraiture, “Poetic Portraits: Allegory & Identity in Sixteenth-Century Europe.” It opened Nov. 5 and is on view through March 29 at the Balboa Park museum.

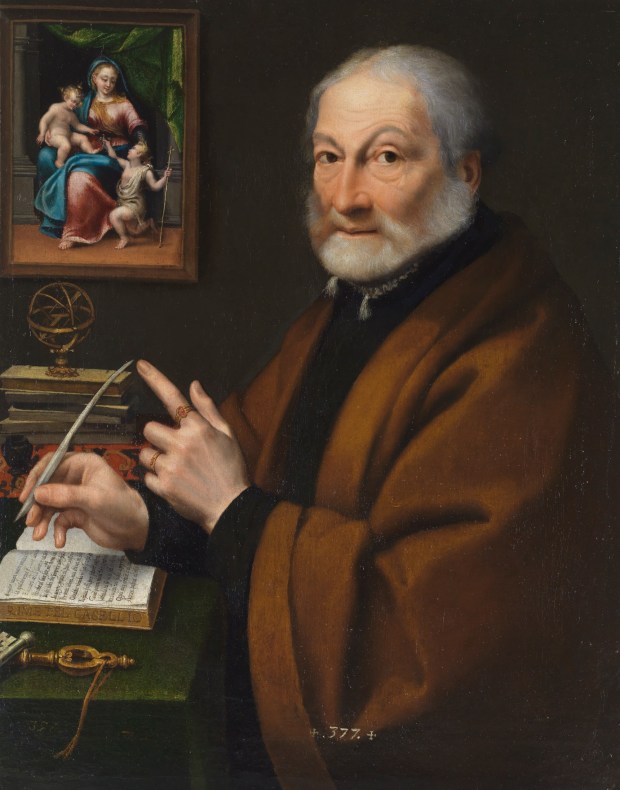

“Giovanni Battista Caselli, Poet from Cremona,” (1557-58, oil on canvas) by Sofonisba Anguissola. (Museo Nacional del Prado)

“Giovanni Battista Caselli, Poet from Cremona,” (1557-58, oil on canvas) by Sofonisba Anguissola. (Museo Nacional del Prado)

Q: Tell us more about the genesis of this exhibition. How did it come to be at the Timken?

A: This exhibition grew out of an opportunity to borrow a painting from the Prado Museum in Madrid. Earlier this year, the Timken lent its only work by Paolo Vernonese, a 16th-century Venetian painter of huge renown, to the Prado’s blockbuster exhibition devoted to the artist. When we asked for a painting in return, we knew that Sofonisba Anguissola, another leading artist from that time period, was well represented within the Prado’s permanent collection.

Since the Timken has depth in 16th-century art but owns no Renaissance representations by women artists, it was a priority for us to bring something by her to the institution. Megan Pogue, the director, successfully negotiated to exchange our Veronese loan for Sofonisba’s portrait of “Giovanni Battista Caselli, Poet of Cremona,” and from that moment forward, we knew we had the makings of a worthwhile exhibition.

“Portrait of a Lady in a Green Dress” (1530, oil on panel) by Bartolomeo Veneto. (Putnam Foundation, Timken Museum of Art)

“Portrait of a Lady in a Green Dress” (1530, oil on panel) by Bartolomeo Veneto. (Putnam Foundation, Timken Museum of Art)

Q: You’ve called this a “landmark exhibition” for the Timken, San Diego and the United States. What makes this such an important exhibition?

A: Scholarship on women artists of the Renaissance has become an increasingly important part of the art history discipline. Past generations of academics vastly underestimated the number of women making a living as artists during the 15th to 17th centuries.

When Giorgio Vasari published his monumental biographical study “The Lives of the Artists” in 1550, he mentioned only a few women mentioned in a text dominated by men like Raphael, Michelangelo and Leonardo.

By the time the second edition of “The Lives …” appeared in print, in 1568, Vasari noted a handful of standout artists who were women — among them Sofonisba Anguissola.

Today, she is admired by scholars for her portraits and devotional paintings. Her work has been included and featured in numerous museum surveys, most recently in Boston and Detroit. Next year, a major monographic study of Sofonisba’s life and lasting reputation will appear in print.

“Poetic Portraits” is, in part, a belated reconsideration of this artist’s role in shaping our understanding of this period and women artists’ roles in visual culture more broadly.

“Poetic Portraits” will eventually include two works by Sofonisba, hung side by side. However, a small painting owned by (San Diego Museum of Art) is currently in Seoul; when it returns from an exhibition there, it will go right to the Timken, thanks to our generous colleagues next door. Thank you, Michael Brown!

“Guy XVII, Comte de Laval” (ca. 1540, oil on oak panel) by François Clouet (Putnam Foundation, Timken Museum of Art)

“Guy XVII, Comte de Laval” (ca. 1540, oil on oak panel) by François Clouet (Putnam Foundation, Timken Museum of Art)

Q: The work that anchors this exhibition is a painting by Sofonisba Anguissola, one of the most celebrated women artists of the Renaissance. Tell us more about her and her place in art history.

A: Sofonisba Anguissola grew up in Cremona, Italy, in a fairly large family that fully supported her creative efforts. Sofonisba had an opportunity to study with leading artists of Cremona, and she advanced quickly as an apprentice. Her father was proud of her progress, and he is said to have sent her drawings to Michelangelo, who would have been quite old at the time.

Legend has it that Michelangelo admired the young artist’s work and encouraged her career. Later on, after her reputation as an artist was secure in her hometown, she was invited to join the Spanish Court, where her talent flourished.

Sofonisba was an artist whose success enabled her to travel quite widely in her own time and, as this project demonstrates, her work still holds tremendous appeal for current generations of art enthusiasts. Only a handful of her works can be found in the U.S. today, so it is nice that she is traveling the globe again.

Q: Some viewers might be intimidated by the title “Allegory and Identity in Sixteenth-Century Europe.” What guidance can you offer viewers when seeing this exhibition to help them understand and appreciate the works?

A: Art historians have a bad habit of putting colons in the middle of their titles, I suppose. “Poetic Portraits” is intended to be a straightforward description of what visitors will encounter in the Timken’s temporary exhibition space. That is, 13 works of art that share the common theme of portraiture at bottom. “Allegory and Identity in Sixteenth-Century Europe” is a mouthful but points toward the project’s finer takeaways.

The fact is, portraiture changed during this period, moving away from images based in profile renderings — which were somewhat easier for artists to make — to three-quarter views of their sitters’ faces — which were considered more revealing of the individual.

The way in which artists conceived of a portrait’s purpose evolved, too. In the early 16th century, symbolism and allegory were frequently deployed when making a formal image of someone. Who they were in the world might be signaled by what they held in their hands or what was displayed nearby.

By the end of the 16th century, a likeness did not depend so heavily on those attributes. A more modern conception of identity with the face as an index of personality prevailed. Tracing this development enables us to think more critically about our own relationship to image production. Think of the selfie: I wonder what Renaissance beholders would make of a new genre where the maker alone determines the look and longevity of the portrait? Something to think about when visiting this exhibition.

“Portrait of a Youth Holding an Arrow” (1500-10,

“Portrait of a Youth Holding an Arrow” (1500-10,

oil on panel) by Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio (Putnam Foundation, Timken Museum of Art)

“Poetic Portraits: Allegory & Identity in Sixteenth-Century Europe”

When: Through March 29. 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Wednesdays-Sundays

Where: Timken Museum of Art, 1500 El Prado, Balboa Park

Tickets: Free

Phone: 619-239-5548

Online: timkenmuseum.org