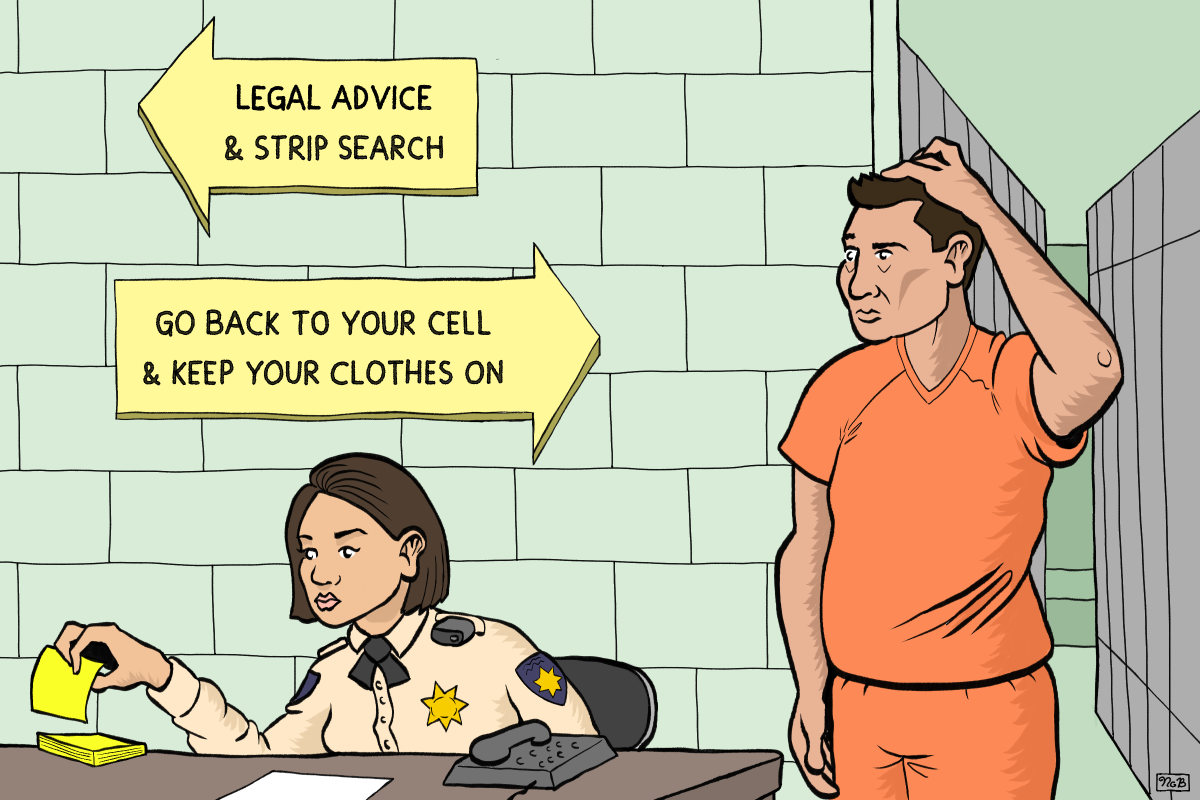

In September, sheriff’s deputies began routinely strip-searching people being held in the San Francisco jail after they met with their attorneys.

The sheriff’s department described this change as the implementation of a long-standing city policy that allows the department to strip-search an inmate after every in-person visit in order to stem the flow of contraband like drugs, cell phones and weapons.

Attorneys, people in custody, and people who work at San Francisco jails said this was the first time they’d ever seen such a practice.

Public defenders and private defense attorneys raised concerns that the strip-searches were already having a “chilling” effect on clients seeking their constitutional right to legal counsel. In particular, they worried about people with a history of trauma or physical abuse.

Defense attorneys with the Bar Association of San Francisco contacted the sheriff’s attorney. The American Civil Liberties Union sent a letter to Sheriff Paul Miyamoto (citing, in part, Mission Local’s reporting) that urged Miyamoto to reconsider the practice.

Their complaints were heard.

Starting next Monday, deputies will implement a new procedure: putting people in custody through a body scanner after meetings with their attorneys instead of forcing them to undress and undergo a search.

“The defense bar spoke. The sheriff listened, and a solution came to bear,” said Rani Singh, the sheriff’s chief legal counsel.

Even though strip-searches are legally within the sheriff’s right, Singh said, the department “didn’t want any impact on due process rights.” The directive to use body scanners instead of strip searches was introduced “solely for the purpose of collaborating with the defense bar,” Singh said.

Strip-searches will be conducted after these scans if it seems necessary, Singh added. Body cavity searches will only be conducted if contraband appears on the scanner inside such a cavity, Singh said.

The sheriff’s decision came after discussions of the policy during at least two monthly meetings of the Bar Association of San Francisco’s criminal justice task force, which includes representatives from the sheriff and public defender’s offices.

Advocates also reached out to the sheriff’s office directly, complaining that strip-searches were slowing down the court system.

Clients had declined in-person visits after being informed they’d be strip-searched, attorneys told Singh. Several lawyers had to request delayed hearings because they were unable to speak with their clients, ACLU attorney Avram Frey wrote.

In every carceral facility, Frey said in an interview, most contraband comes in from staff. A more effective policy would be to screen people working in the jail for contraband, or to search detainees based on individual suspicion, he suggested.

The sheriff’s office has yet to issue a formal response to Frey’s letter, but told the ACLU, the San Francisco bar association and the public defender’s office that a “procedural update” would address their concerns.

Was this ever legal?

The sheriff’s written strip-search policy has still not changed. Several attorneys questioned the legality of “blanket” strip-searches, which can be conducted after any in-person visit without reasonable suspicion of contraband being exchanged.

Whether inmates can be strip-searched after meeting with their lawyer hasn’t been challenged in court before, said Michael Bien, an attorney who has litigated several class action lawsuits against correctional agencies.

The policy could be legally challenged in two ways, legal experts said: A plaintiff could argue that blanket strip searches are unconstitutional, or that they are being administered in a discriminatory way.

But most attorneys today would be hesitant to take up the matter, said attorney Mark Merin. This is despite the fact that Merin, in 2004, won a record $15 million settlement from the Sacramento Sheriff’s Department after arguing that their practice of strip-searching people accused of both felonies and misdemeanors violated California Penal Code.

Merin pointed to a subsequent 2010 case in which the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the San Francisco Sheriff’s Department’s policy mandating blanket strip-searches of all arrestees before placing them in the general jail population for custodial housing.

These days, Merin said, “courts aren’t going to step in and prevent this policy from happening.”