Stage director Cameron Watson has one of the best batting averages in town.

His productions of “The Sound Inside” at Pasadena Playhouse, “On the Other Hand, We’re Happy” for Rogue Machine Theatre at the Matrix and “Top Girls” at Antaeus Theatre Company were morale-boosting for a critic in the trenches, offering proof that serious, humane, highly intelligent and happily unorthodox drama was alive and well in Los Angeles.

Watson’s appointment as artistic director of Los Feliz’s Skylight Theatre Company starting Jan. 1 is good news for the city’s theater ecology. Producing artistic director Gary Grossman, who led the company for 40 years with enormous integrity, built Skylight into an incubator of new work that embraces diversity and the local community.

Developing new plays is fraught with risk. Watson has the both the artistic acumen and audience sensitivity needed to usher Skylight through this perilous moment in the American theater when so many companies seem to be holding on by a thread.

Watson’s production of “Heisenberg,” which closes Sunday at Skylight, showcases one of his signal strengths as a director: his ability to balance complicated emotional material with playful dramatic form. Simon Stephens’ drama, presented at the Mark Taper Forum in 2017, is a two-hander that tests the validity of the uncertainty principle in the arena of human relationships.

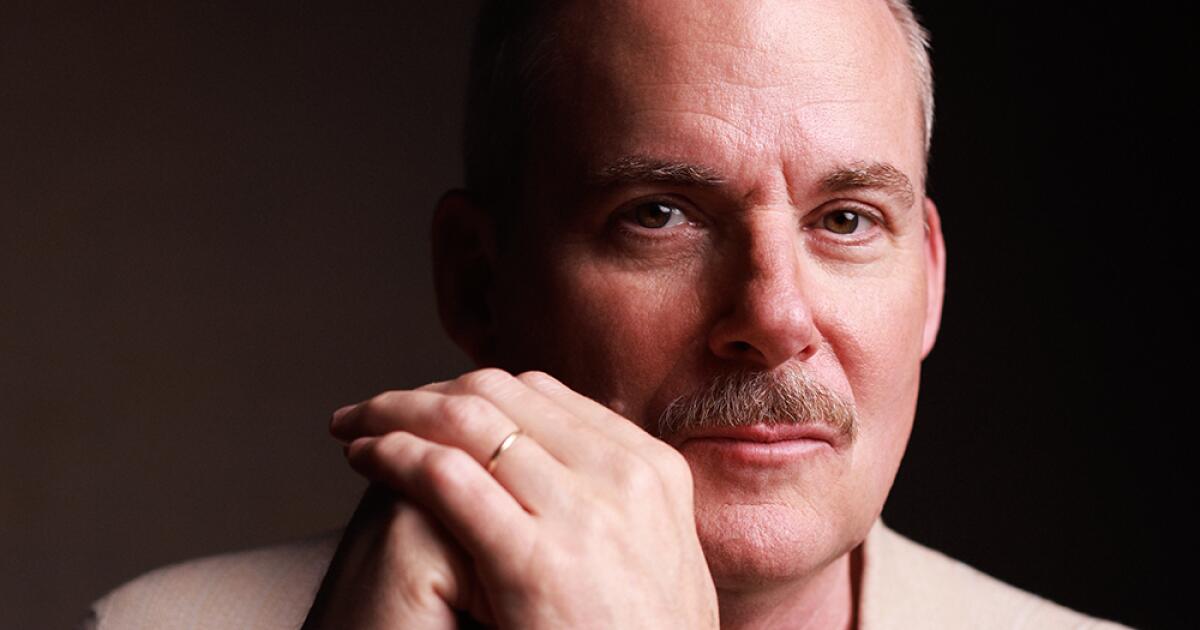

Juls Hoover and Paul Eiding star in “Heisenberg” by Simon Stephens, directed by Cameron Watson at the Skylight Theatre.

(Jeff Lorch)

German physicist Werner Heisenberg’s great insight, from a theater critic’s science-lite perspective, is that there are tradeoffs in what can be known. He was examining the related but distinct properties of speed and position. But Stephens is dealing with something even more complex — the emotional variables of love. In this case, it’s the love between two unlikely people, Alex Priest (Paul Eiding), a London-based bachelor butcher in his mid-seventies, and Georgie (Juls Hoover), a manic fortysomething American woman who careens into his life like an unstoppable drone.

In the Broadway production from Manhattan Theatre Club that appeared at the Taper, Mary-Louise Parker (who starred opposite Denis Arndt) endowed Georgie with her signature raspy charm and eccentric wiles. The character, a compulsive talker whose social manner is as subtle as a leaf blower, poses a tremendous acting challenge, being as intensely annoying as she is mysteriously alluring. Alex falls in love with her, and the audience must be able to put up with her.

Hoover, unsteady in the early going, gets better as the production settles into a groove. But her raucous Georgie made me wonder why this solitary older gentleman was tolerating her intrusive madness.

Eiding’s portrayal hints at a man awakening to his own loneliness. He’s contending with something deeper than Georgie’s suspicious and off-putting nature. He’s reckoning with the old wounds and stark compromises that have left him isolated at the twilight of his life.

How does anyone wind up where they are? As Alex comes to learn, not being able to predict one’s future position may be the secret to happiness.

This story of mature love survives not only the threat of Georgie’s mercenary motives but also a shoestring production that is forced to make do with a drab set and a discrepancy in the level of performances. But the humanity of the play shines through like a light from a dwindling candle that refuses to give up its flame.

Watson, like Peter Brook before him, knows how to convert an empty space into a realm of magic and meaning. For Watson, the play’s the thing. But for the spark to happen, actors and audience members need a director as intuitively attuned to the uncertain human drama as Skylight Theatre Company’s new leader.