TAMPA, Fla. — This Black History Month, the legacy of former Florida A&M University President Dr. Walter Lee Smith is being remembered not only for strengthening one of the nation’s leading HBCUs, but for extending its reach across the African diaspora.

What You Need To Know

During Black History Month, Tampa’s library honoring Civil Rights activist and FAMU 7th President Dr. Walter L. Smith lands an $800,000 grant, advancing a legacy that reached from Florida to Africa and Haiti

Smith led FAMU from 1977 to 1985 — a period marked by post-Civil Rights era expansion in higher education and political instability in parts of the Caribbean and Africa

At the invitation of Haitian officials, Smith traveled to Haiti multiple times to assist following a “brain drain” and intellectual exodus during the Duvalier Era

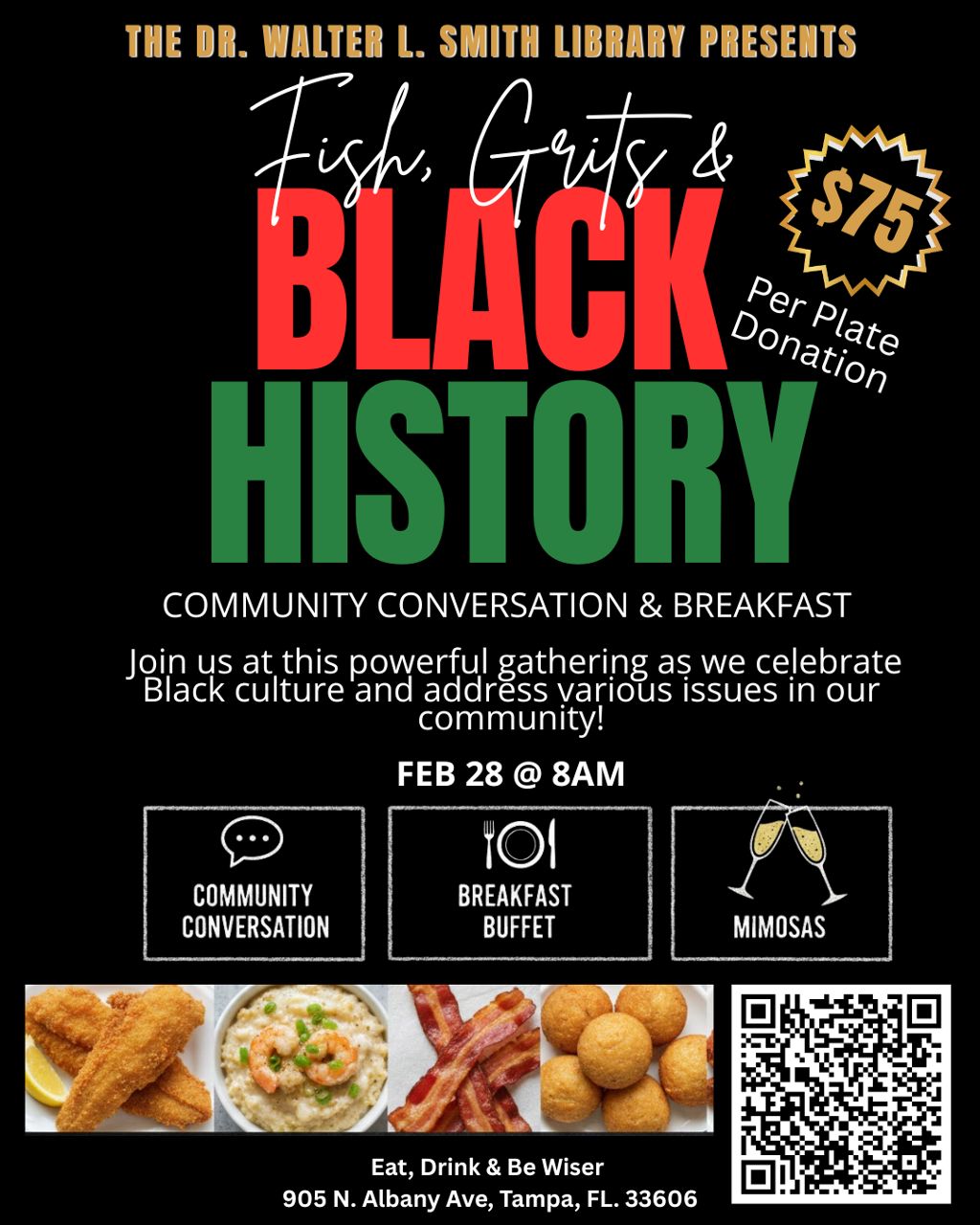

On Saturday, Feb. 28 at 8 a.m., the Walter Smith Library & Museum will hold its yearly Black History Month event titled “Fish, Grits & Black History”

Dr. Smith led FAMU from 1977 to 1985 — a period marked by post-Civil Rights era expansion in higher education and political instability in parts of the Caribbean and Africa.

His son says his father saw education as something far bigger than a degree.

“Dad internationalized FAMU under his administration,” said Walter L. Smith, Jr.

Building bridges during Haiti’s Duvalier Era

In the early 1980s, during the presidency of Jean-Claude ‘Baby Doc’ Duvalier, Haiti was facing political repression and an accelerating “brain drain.” Professionals and university-educated Haitians were leaving the country in large numbers — many bound for the United States, France, and Canada.

At the invitation of Haitian officials, Smith traveled to Haiti multiple times.

His mission: strengthen academic standards and create partnerships that would allow Haitian degrees to be recognized internationally.

“What that Dad did was help to establish that articulation so that when people who had degrees from those colleges would go to Western Bloc countries, their degree would be of the same caliber or the same validity,” said Smith Jr.

Smith’s work came against the backdrop of a dictatorship that began under François Duvalier and continued under his son. Despite political instability, Haitian officials sought educational infrastructure support.

“Despite the despotic nature of the government and of the family, they wanted my father to come and help,” said Smith Jr.

Smith was often joined by his wife, FAMU’s seventh First Lady, Jeraldine Williams.

“I’ve been to Port-au-Prince and Cap-Haïtien,” said Williams.

She says Smith’s focus was not simply elite university access, but practical, workforce-driven education.

“High on his (Dr. Walter Smith) list of agenda items was to install two-year schools, two-year colleges,” said Williams.

The goal was to create local two-year institutions that could provide credentials, workforce training, and pathways to four-year degrees.

“So they got a degree, they have a certificate, and so they are qualified to perform at some level rather than not be,” Williams added.

Williams says Smith deeply worried about the long-term effects of intellectual migration and “brain drain.”

“Those who had the brain power would go away, let’s say, from Haiti to the United States, or Haiti to France, or Haiti to England. And then they wouldn’t come back. So that’s a loss. There is an enhancement for them, but it’s a loss for the country,” she said.

A home for Haitian students at FAMU

Some Haitian students did come to Florida, enrolling at FAMU during Smith’s presidency.

Williams says many faced cultural and linguistic barriers.

They found opportunity and support.

“(Smith) was trying to deal with those people who were coming in, who probably felt more at a greater distance from success than he did because of the language, because of tradition, because of expectation,” Williams said.

For Smith, education was about empowerment and nation-building. His work extended beyond the Caribbean.

During the late 1970s and early 1980s, Smith also traveled to African nations, part of a broader effort by historically Black colleges to reconnect with the global Black diaspora following the Civil Rights movement.

“Education was a sign of status and still is,” said Smith Jr. “If you had an education, especially a college education, you are big time. You’re doing something right. And that was the basis of the values, is to what was to create a society that could help them to grow that infrastructure.”

And to his son, there was never a question about whether the work was worth it.

“There’s never a time that I’ve ever witnessed my father not think the education of Black people was not worth it. He put it all on the line for more than half of his life,” said Smith Jr.

Smith’s lasting global impact on the Black diaspora

Today, decades after his presidency, the influence of Dr. Walter Lee Smith’s legacy continues to cross borders.

The Walter Smith Library & Museum in Tampa recently received an $800,000 grant from the Tampa Community Redevelopment Agency. On Feb. 28, the library will hold its yearly Black History Month event, titled “Fish, Grits & Black History.”