The voting power of Black and minority communities faces fresh threats as the U.S. Supreme Court and Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis are poised to reshape electoral maps, moves that critics warn could weaken decades of civil rights gains ahead of next year’s midterm elections.

Justices reviewing a Louisiana case are expected to rule in coming weeks to limit the use of race-based electoral districts, a sharp erosion of the decades-old Voting Rights Act.

Against that backdrop, DeSantis is already clamoring for Florida lawmakers to hold a rare, mid-decade redistricting session, likely targeting the state’s two Black-leaning congressional districts.

For many Black Floridians, it’s all too familiar.

“What we see happening with the mid-decade redistricting effort is just one in a long line of attacks not just against Black Floridians, but frankly, all Floridians,” said Genesis Robinson, executive director of the Equal Ground Education Fund, a voting rights organization.

The U.S. Supreme Court may give strength to Gov. Ron DeSantis’ call for rredrawing Florida’s congressional map, the latest in a series of moves that have diluted minority voting power.

The redistricting drive comes on top of a series of Florida laws passed since 2020 that restrict vote-by-mail, toughen voter ID requirements and undermine voter registration efforts by independent groups, all of which experts say have particularly hurt minority voting.

During the last round of redistricting, in 2022, DeSantis said he was seeking a “race neutral” congressional district across North Florida. The plan he promoted effectively eliminated a seat held by U.S. Rep. Al Lawson, a Black Democrat from Tallahassee. Thousands of Black voters were scattered into three Republican-held districts.

“Race neutral, c’mon, really? What’s that a code word for?” said Cynthia Slater of Daytona Beach, who helps lead voter outreach efforts for the non-partisan, Florida NAACP.

Slater was at the U.S. Supreme Court for the Oct. 15 challenge to a Black majority congressional district in Louisiana, which non-Black voters condemn as racial gerrymandering.

Majority of justices look ready to revamp Voting Rights Act

The six conservative justices on the nine-member court seemed inclined to strike down the district because it relies too heavily on race. Such a ruling would amount to a central change in the 1965 Voting Rights Act, which promoted using race as a consideration in district line-drawing to remedy past discrimination.

Now, justices appear ready to open the door to more redistricting efforts that eliminate many Black and Hispanic seats, which tend to favor Democrats.

“The Constitution prohibits discrimination based on race, which is why the Court is likely to find racial gerrymandering to be unconstitutional,” DeSantis posted on X about the Louisiana case.

President Trump is pushing states where Republicans control the Legislature to redistrict to improve the GOP’s chances of winning enough seats next year to retain control of Congress. The party of the seated president historically loses seats in the midterm elections.

Florida could follow lead of Texas, Missouri, now North Carolina

Republicans are looking to achieve this goal by redrawing a host of seats now held by Black Democrats. Texas, Missouri and now North Carolina are advancing new congressional maps to meet Trump’s demand.

Democratic-led California has swung back with a map of its own, improving that party’s chances. But voters in November must decide whether to go ahead with the plan.

Widely expected to be the focus of a Florida redistricting re-do would be the South Florida seats held by U.S. Reps. Frederica Wilson and Sheila Cherfilus-McCormick. While neither has a majority Black voting population, Wilson’s is 41% Black and Cherfilus-McCormick’s is 49% Black.

Another Democratic seat likely targeted is U.S. Rep. Darren Soto of Orlando. His district is 49% Hispanic.

DeSantis, though, is expected to seek a way to preserve the state’s three, longtime Hispanic majority seats in South Florida – held by Republicans.

Florida’s congressional map already heavily favors Republicans. Under the new DeSantis-crafted map, Republicans won an additional four seats in 2022 and continue to control 20 of the 28 U.S. House seats from Florida.

Is Florida next? Is Florida next? State GOP leaders respond to Trump’s call for redistricting

Third-party groups hurt… Grassroots groups end voter registration drives, fearing Florida law pushed by GOP

The state’s Fair Districts constitutional amendments, approved by voters in 2010, bar lawmakers from drawing districts intentionally to help or hurt a party.

Still, DeSantis and Republican leaders see a path to change what justices may conclude are districts that overly favor minorities at the expense of white voters.

As many as five Democratic-held seats could be made more competitive for GOP

All told, as many as five Democratic-held congressional seats could be eyed for becoming more competitive for Republicans if redistricting occurs in the next legislative session, which begins in January.

DeSantis and the Legislature in recent years have approved a spate of election law and voter-access changes which analysts say already contributed to a marked decline in Black voter turnout.

Florida Republicans say the new requirements enhance confidence in elections. They also reflect the unfounded doubts continually raised by Trump about the integrity of elections.

In the 2020 presidential election, 65.6% of Black voters cast ballots, according to the University of Florida Election Lab. In last year’s contest, that level slumped to 59.8%. White voter turnout remained mostly steady – with 72.6% in 2020 and 71% in 2024.

Almost three-out-of-four Black voters are registered Democrats in Florida, where Republicans have surged to an almost 1.4 million-voter lead over Democrats, according to the Division of Elections.

Minority voter access hurt by Florida’s recent changes, experts say

Florida’s new limits on drop boxes, mail ballot requests and third-party voter registration groups also have dampened minority voter access, experts say. An Office of Election Crimes and Security was established by DeSantis in 2022, which some opponents cast as a tactic that could intimidate many minority voters.

A voter-approved effort in 2018 to restore voting rights to those with past convictions who completed terms of their sentences has had a limited effect on the 1.4 million Floridians it was designed to help, records show.

Steep fines imposed on organizations registering voters, once a key part of work by the League of Women Voters and the NAACP, has largely limited such activity.

One-in-10 Black voters and the same share of Hispanic voters in Florida had registered through these third-party groups. By contrast, fewer than one-in-50 white voters who became eligible to vote were assisted by these groups, according to analysis by University of Florida political scientist Daniel Smith.

While more than 63,000 Floridians registered to vote through third-party organizations a year before the 2020 election, that figure has now dwindled to 1,089 this year.

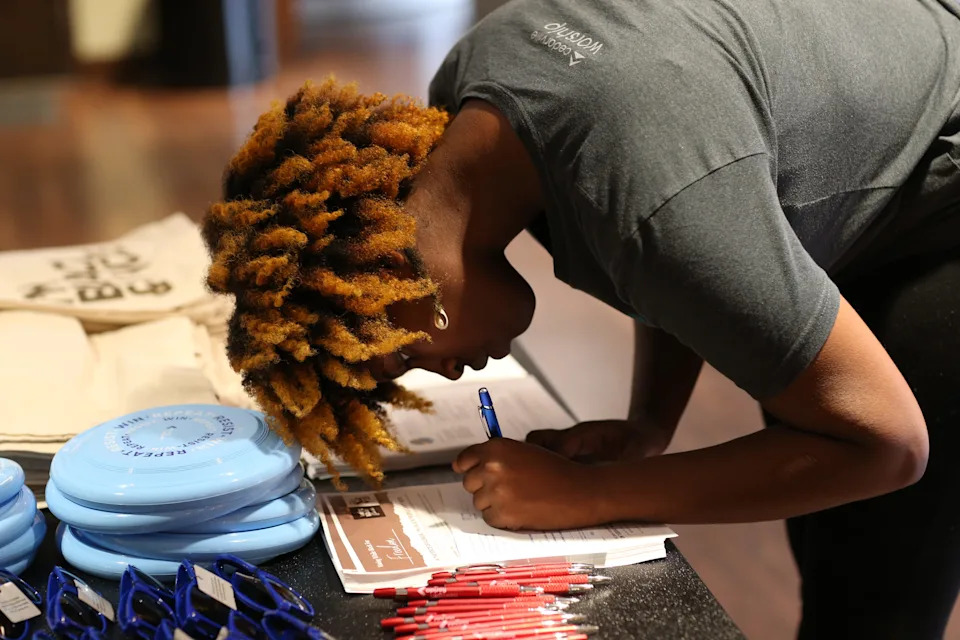

“They’ve definitely chipped away at our ability to get out to our community,” said Cassandra Brown of Leesburg, co-founder and executive director of All About the Ballots, which helps voters register.

“Now we mostly direct people to Elections Supervisors websites or provide stamped envelopes for them to send in their registration applications,” she added. “We can really only make sure that they fill out their applications and tell them where they can drop them off.”

Asked if she felt the changes by Republican leaders were designed to keep those unregistered from ever getting a chance to vote, Brown said. “Absolutely. It’s intentional and strategic. They know what they’re doing.”

And Brad Ashwell, Florida director of the All Voting is Local, a national organization that advances pro-voter policies, said DeSantis’ drive to redraw congressional district boundaries would occur as voting patterns are already changing.

“Anytime you erect a hurdle, new requirements, these are going to disproportionately affect people who have already marginalized; those who are kind of on the fringe of voting,” Ashwell said. “And these are mostly minorities, younger people and people with disabilities.”

John Kennedy is a reporter in the USA TODAY Network’s Florida Capital Bureau. He can be reached at jkennedy2@gannett.com, or on X at @JKennedyReport.

This article originally appeared on Tallahassee Democrat: DeSantis’ redistricting fight in Florida puts Black voters on the line