STUART — More than three years after Robert and Olga Hamilton of Stuart applied for a Community Development Block Grant to help restore a historic church they own, the project remains stalled amid disputes over contractors and the grant process.

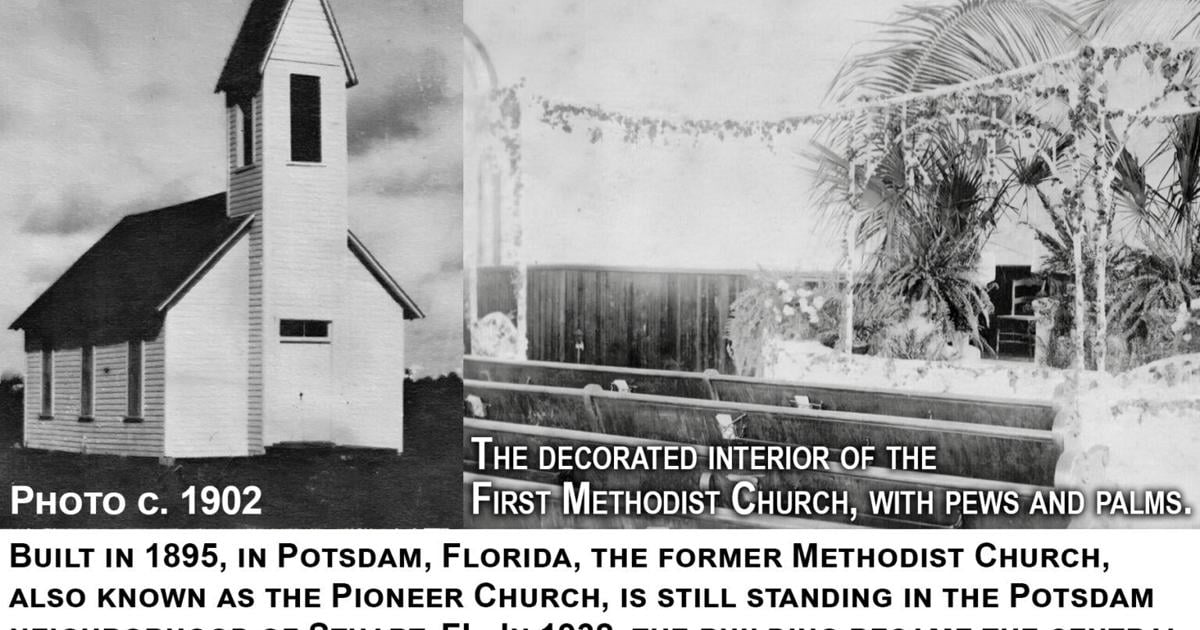

The couple purchased the 1895 structure at 311 S.W. 3rd St. in 2019 with plans to make it their home and an art gallery. They renamed it the 1895 Church of Stuart to honor its history. Built as Stuart’s first Methodist church, the building was later moved and became home to St. Mary’s Episcopal Church.

The Hamilton’s signed CDBG documents in 2023 naming Guardian Community Resource Management as grant manager and Patriot Response Group as contractor. But after crews replaced the roof, the couple said they noticed problems: missing ridge ventilation and windows that didn’t fit.

“According to the scope of work, the contractor was responsible for all the measurements,” Olga Hamilton told city commissioners Sept. 22. “When the windows arrived, they didn’t fit. They cut into the historic walls and left gaps.”

Unhappy with the work, the couple stopped construction and pressed the city to bypass competitive bidding rules so they could hire McKee Renovations of Port St. Lucie to finish the job.

Robert Hamilton argued that federal guidelines allow exemptions in certain cases and noted McKee had received approval from the state Historic Preservation Office.

City Manager Michael Mortell pushed back, saying state officials told him otherwise. “They said it has to go through the sealed-bid process, and we must select the lowest bid,” Mortell said. He added that McKee could still bid on the project as an approved contractor.

The clash came into public view in August when commissioners debated a different oversight contract for Project LIFT.

Guardian, the same firm that managed the Hamiltons’ grant, was chosen for that role. Commissioners were assured Patriot would not be involved in the LIFT project.

At the Sept. 22 meeting, Olga Hamilton presented videos highlighting the church’s role in local history, including a clip of the late historian Alice Luckhardt calling it Stuart’s first community church and a 2000 interview with Jo Marie Paradise, great-granddaughter of founder Walter Kitching.

The Hamiltons said their goal is preservation. “Alice told us behind the drywall was the original beadboard,” Olga said. “We found it in the attic and began restoring it.”

But commissioners were less focused on the building’s history than on procedure. Mortell suggested the Hamiltons confused being allowed to select a structural engineer—under a $5,000 threshold—with choosing a general contractor. Guardian had already drafted a revised scope of services approved by the Department of Commerce, he said, but the Hamiltons had refused to sign.

City Attorney Lee Baggett advised that bidding is required, though McKee could still emerge as the contractor. “If they’re one of three bidders, the Hamiltons can select McKee, even if they’re the highest bid,” Baggett said.

Guardian’s grant consultant, Antonio Jenkins, confirmed the city’s housing policy requires competitive bids. “Your policy is not going to allow that exemption,” he told commissioners. “You’re going to have to go through the Commerce-approved process.”

By the end of the meeting, commissioners placed responsibility back on the couple. “The Hamiltons need to sign it,” Mortell said. “We’ve signed it, we’ve agreed to it, and we’re ready to submit it.”

Vice Mayor Christopher Collins asked Robert Hamilton if that was reasonable. Hamilton did not answer directly but acknowledged relief that the grant’s second mortgage would be forgiven after five years.

Mayor Campbell Rich closed the debate. “We have gotten to the point where we wait until the Hamiltons sign the scope of service,” he said.

For now, the 1895 Church of Stuart remains in limbo, its future tied not only to construction work but also to how the city and the Hamiltons navigate federal rules designed to govern the preservation of historic structures.