A rare Rice’s whale swims just under the surface of the Gulf of Mexico. (Photo via NOAA/Ocean Alliance)

If you haven’t picked a Halloween costume yet, I have a suggestion: Dress up as a Rice’s whale.

You maaaaaay need a few friends to help out if you want your costume to look authentic. Rice’s whales are about as long as a Greyhound bus. But what makes this a compelling Halloween outfit is that these massive mammals remain largely (ba-dum-bum!) mysterious.

We often fear the unknown, and the Rice’s whale is definitely unknown. Most people who live along the Florida coast have no idea they’re there. Until recently, scientists didn’t even know for sure they existed.

Now that we do know they exist, we also know that they’re endangered — and that they will likely be harmed or killed by a new plan to expand offshore oil drilling.

“The Trump administration is readying a proposal to open almost all U.S. coastal waters to new offshore oil drilling despite opposition from state governors and the president’s previous efforts to close off some of the territory,” Bloomberg News reported last week.

Even parts of the Gulf of Mumblety-Mumble that he had decreed off-limits to drilling during his last term are included in the current proposal, the Bloomberg report says.

Workers cleaning up the 2010 BP oil spill on Pensacola Beach, via Florida Sea Grant

Expanding offshore oil drilling is bad for a lot of reasons, but it’s especially bad for the Rice’s whales. There are fewer than 100 left, and maybe as few as 50. There used to be more, but the population dropped by about 22% after the 2010 BP Deepwater Horizon spill, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Scientists also estimate that nearly a quarter of the female Rice’s whales that survived the oil spill suffered “reproductive failure.” In other words, they’re now unable to produce healthy, live calves to rebuild the population.

These whales are way too big to compare to canaries, but in a way that’s what they are for our aquatic coal mine.

Laura Engleby via NOAA on X

“Protecting Rice’s whales protects the health of the Gulf,” said Laura Engleby, a recently retired marine mammal scientist for the National Marine Fisheries Service. “They play a really important function in the ecosystem.”

They’re so important, in fact, that saving these whales may just save us humans.

World’s weirdest

I’ve lived near the Gulf nearly my whole life, but I had no idea there were whales out there until one popped up almost in my backyard in 2019.

That’s when a dead Rice’s whale washed up near the Everglades. Scientists pushed it ashore, then swarmed the carcass, taking measurements and samples. They wrapped the 38-foot carcass in a blue tarp, loaded it on a flatbed truck and transported it to St. Petersburg.

There it was buried in a deep sandy pit at Fort DeSoto to make it easier to strip the flesh from the skeleton, which would then go to the Smithsonian. I well remember the day several months later when they dug it back up. It’s not every day you see people with doctorate degrees wielding shovels and reminding everyone to breathe through their mouth, not their nose.

The Smithsonian’s collections manager was particularly eager to get the skull and skeleton to Washington.

“The way this population is going, I don’t know that I’ll ever get another chance,” he told me that day.

In case you were wondering what killed this big creature, it was done in by a small piece of plastic that became lodged in one of its stomachs. In other words, the cause of death should have been listed as human stupidity.

At the time, the scientists were referring to this as a type of Bryde’s whales, which are named after Johan Bryde, a Norwegian who built the first whaling stations in South Africa.

A British newspaper, the Daily Mail, once called Bryde’s whales “the world’s weirdest whale,” because of their oddly eel-like appearance. Given Florida’s rampant and innate weirdness, it made sense to have the weirdest whale show up here.

But the whole time, the scientists suspected it might be something entirely new.

In 2021, scientists announced they were finally sure. This whale was from a species they had never identified before. They named it after Dale Rice, a biologist who had looked at a photo of a whale stranded near the sleepy Panhandle town of Panacea in 1965 and theorized it was a new species.

In the four years since then, scientists have put in a lot of work to learn about these rare mammals. They have lowered microphones underwater to pick up their moaning, mournful cries. They have dropped drones down over them to collect DNA samples. They have mapped their preferred terrain and habits, such as feeding near the sea floor in the daytime but swimming near the surface at night.

One group of biologists spent 21 days at sea in a 70-foot sailboat and floating lab called “The Song of the Whale.”

The Song of the Whale via NOAA

“The team successfully tagged seven Rice’s whales and collected approximately 65 hours of dive and movement data,” NOAA reported last year.

At the rate things are going, we’ll learn everything possible about them around the time the last one dies off.

Time travel for whales

“Save the Whales” has been a rallying cry for environmental groups for decades. Activists were galvanized in 1975 when Greenpeace launched its initial anti-whaling campaign, sending its own boats to confront and stop the blood-soaked whaling ships.

There was even a Save the Whales benefit concert in 1976, featuring Joni Mitchell, John Sebastian, and Country Joe McDonald (who apparently didn’t bring his Fish, perhaps out of fear the whales would eat them.)

Back then there was bold talk about how saving the whales would save us humans. That was even the plot of a popular movie, Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home. The Enterprise crew had to time-travel back to Earth 1986 and rescue a couple of whales that could communicate with a destructive alien civilization threatening to end all humans.

But it turns out to be true. Not the time-travel part, but the rescuing the humans part.

SUPPORT: YOU MAKE OUR WORK POSSIBLE

The one difference is that the civilization destroying the Earth is our own. Our reliance on fossil fuels has created a warming world. As a result, we’re now seeing rapidly intensifying hurricanes like Melissa, beaches repeatedly eroding because of sea level rise, more pollution-fueled toxic algae blooms, and other symptoms of impending disaster.

Our governor and Legislature are fighting back by shutting down discussions of what’s happening, which — surprise! — doesn’t fix the problem. Instead, we should be looking for potential solutions.

The International Monetary Fund — not exactly a gang of wild-eyed tree huggers — says one good strategy is protecting our whales.

“When it comes to saving the planet, one whale is worth thousands of trees,” the IMF said in 2019. “The carbon capture potential of whales is truly startling.”

The whales themselves sequester tons of carbon from the atmosphere, the IMF pointed out. And they attract phytoplankton, which suck up a lot more carbon before it can further heat up the planet.

“Nature has had millions of years to perfect her whale-based carbon sink technology,” the IMF noted. “All we need to do is let the whales live.”

But it seems we just can’t do that.

A little batty

On the surface, so to speak — our size-obsessed president is a yuuuuge fan of whales.

He has repeatedly talked about how much he dislikes windmills because they supposedly kill lots of whales.

“They are washing up ashore,” Trump said in 2023. “The windmills are driving them crazy. They are driving the whales, I think, a little batty.”

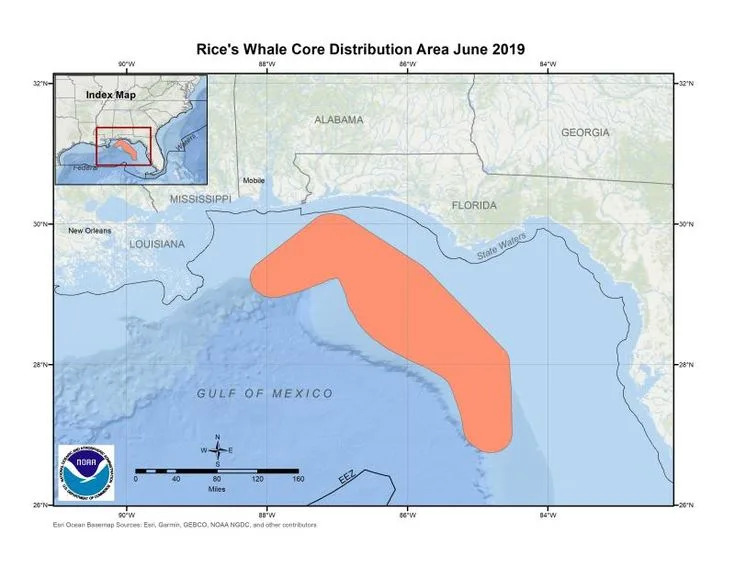

Rice’s whale core distribution in the Gulf via NOAA.

Shortly after he was sworn in for his second term, he signed an executive order halting any new offshore federal leases for wind turbines.

“If you’re into whales,” he said then, “you don’t want windmills.”

There are three yuuuuuge problems with that batty statement:

1) According to NOAA, “There are no known links between large whale deaths and ongoing offshore wind activities.”

2) His minions have stopped providing funding for two scientific research programs that were actually looking into the windmills’ non-lethal effects on whales.

3) Windmills aren’t nearly as bad for whales as offshore oil drilling.

Seismic surveys for offshore wind turbines and noise during their operation can cause problems for whales coping with the underwater clamor. But with offshore drilling, you get all the noise of the offshore wind industry, plus the additional risks of toxic oil spills that poison them and vessel traffic that can clobber them.

In fact, five months ago, NOAA issued a biological opinion that said offshore oil drilling in the Gulf could doom the Rice’s whale to extinction unless the industry finds ways to lessen its impacts.

That’s not going to stop the plans to expand oil drilling, though. Our dear leader is insisting we’ve got to drill, baby, drill, because our energy industry is facing a dire national emergency.

Except it’s not.

As one smart aleck (okay, it was me) wrote in January when Trump declared the energy emergency: “During Biden’s four years in office, the oil companies set records for both oil production and oil and gas company profits. Their only emergency is finding new pockets in which they can stuff all that cash.”

Instead, the oil industry is employing all its political influence to avoid being held liable for the damage done to our climate. If only they’d realize that the whales could help them out.

Sea of chaos

A lot of environmental groups are gearing up to oppose this unnecessary offshore expansion. One of them is called Healthy Gulf.

Christian Wagley via Healthy Gulf

Healthy Gulf’s Florida and Alabama organizer, Christian Wagley, told me they’re lining up scores of elected officials, business folks, and concerned coastal residents to bombard the federal government with their reasons for opposition.

They will cite the BP oil spill’s obvious harm to the economy, chasing away tourists and spoiling everything from tourism to seafood. They will also bring up the harm to the whales and other wildlife.

“These are amazingly beautiful animals that are trying to survive in an industrialized sea of chaos,” Wagley told me. “They just need a little bit of quiet space to survive, and that’s not compatible with an aggressive plan for expanded offshore drilling.”

To boost participation — and increase public awareness — Healthy Gulf has been staging an annual springtime Gulf Coast Whale Festival on Pensacola Beach for the past two years.

Tommy Tucker (Photo via Linkedin)

One of the people helping with the festival is a woman named Tommy Tucker, who’s listed as a “whale biologist and artist.” She makes whale puppets and banners to show people the size and features of the Rice’s whales.

During this year’s festival, she told me, she met a family who had been to the last one.

“I asked the kids what they knew about whales, and they told me, ‘Oh, we came last year, and we learned all this stuff,’ and they started rattling it all off from memory,” Tucker said. “That’s the whole reason we’re doing this.”

On second thought, maybe the scariest Halloween costume isn’t a Rice’s whale outfit.

Instead, I think you should dress up as an offshore oil well, one that’s leaking all over the place like Deepwater Horizon.

Because that’s what’s going to doom the whales and then doom us all.

Visitors to the 2025 Gulf Coast Whale Festival in Pensacola Beach walk through an inflated version of the Rice’s whale. (Photo via Tommy Tucker)

SUBSCRIBE: GET THE MORNING HEADLINES DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX