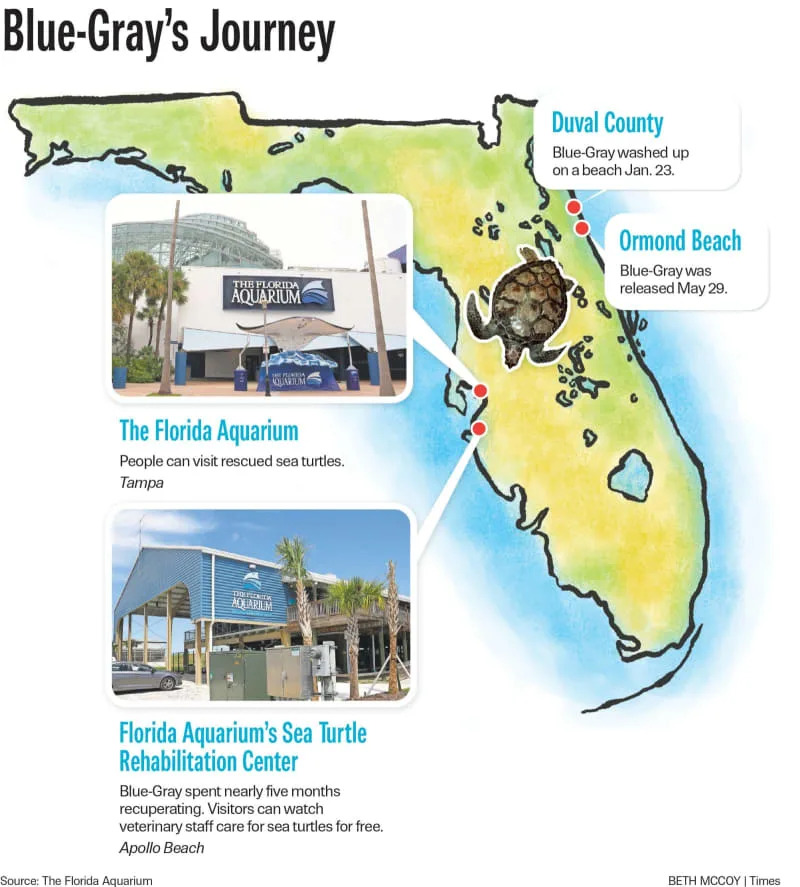

On one of the coldest mornings ever in Florida, a young green sea turtle flailed through freezing surf. Too stunned to swim, he got caught in currents, walloped by waves, until he washed up on a Duval County beach.

Rescuers found him caked in sand, his flippers flaccid, his bulgy eyes half-shut. He couldn’t lift his head.

Eleven others languished nearby — all juveniles, about the size of dinner plates.

The crew bundled the turtles in towels and set off. Their ultimate destination: one of the state’s biggest turtle hospitals, on the edge of Tampa Bay, where a vet tech and her team rushed them inside in wheelbarrows.

The worst season in recent memory for distressed turtles in Florida was just beginning — a harbinger of the peril to come as climate change wreaks havoc on their habitat.

Some turtles would stay for weeks to rehabilitate. Others, injured and diseased, might stay months — or never make it home.

Workers clipped colored bands around the turtles’ flippers, which became their names.

When the rescues from that frigid beach arrived, staff ran out of colors and had to double up the bands.

The one caked in sand became Blue-Gray.

As the team at the Florida Aquarium’s Sea Turtle Rehabilitation Center sorted patients into pools, they began to confront a problem. With eight new pools, they had room for 20 turtles.

Now they had 29, and it was only January. More, they worried, would soon be on the way.

All winter, the cold-stun crisis crescendoed down the Atlantic, thousands of dying turtles washing ashore from Cape Cod to Cape Canaveral.

Rescuers pulled them from shallow shorelines, carried them through marshes in kayaks, laid them on tarps along beaches.

Florida officials would rescue an astounding 1,410 cold-stunned turtles in 2025.

The year before, they’d rescued 66.

Status: Threatened

Florida presence: Nests each year along both coasts, typically June–September

ID tips: The largest hard-shelled sea turtle, reaching 400 pounds. Smooth brown or olive shell with a small-ish head and pale underside. Two scales between the eyes.

Fun fact: Unique among sea turtles in that adults are mostly herbivores, preferring seagrasses and algae.

Top threats:

Accidental capture in fishing gear

Beachfront development & coastal lighting

A combination of climate events caused the surge, experts said. The biggest factor in the cold strandings, ironically, seemed to be warming waters.

As sea temperatures rise, turtles are swimming further north to reach cooler currents. They used to never nest above North Carolina. A few years ago, some began laying eggs along Assateague Island, Maryland.

Green sea turtles travel alone, up to 50 miles a day. Many who were too young to nest made their way to Massachusetts last fall, showing up much earlier than usual. When the cold came, the turtles were caught off guard in freezing water, too stunned to migrate south.

Sea turtles prefer balmy water, 75 to 80 degrees. When the temperature dips into the 50s, they become lethargic and float to the surface, where cold air makes it harder to breathe. Reptiles can’t regulate their body temperatures like mammals and birds, so they become immobilized, almost frozen — like a severe form of frostbite.

At the Apollo Beach hospital, workers fielded frantic calls from staff at northern aquariums, overwhelmed with turtles, begging them to take some in.

Volunteer pilots picked up banana boxes full of fading turtles in New Englandand flew 10 to Tampa — just before the Sunshine State got its own cold snap and rare onslaught of victims, including Blue-Gray.

The young turtles had been through so much already. Hatchlings start out the size of a credit card, traverse dunes and escape seagulls, then sharks. In a single season, they might travel a thousand treacherous miles.

“These are the fighters, the ones who want to survive,” said Debborah Luke, vice president of the Florida Aquarium. “They’ve overcome so many obstacles to become our ICU patients. They have the will to live, so we have an obligation to help them.”

A couple years ago, Florida had 15 sea turtle hospitals. But hurricane damage in Sarasota and Clearwater kept those aquariums from taking in rescues this year. As the only turtle rehab on the Gulf Coast, Apollo Beach strained against its limits.

“We’re feeling pressure to bring in more and more. But there’s no room. The inn is full, and there’s not enough money,” aquarium president Roger Germann said in January. “It’s so complicated and emotional. We’re going to have to make some unfortunate decisions.”

It takes up to a year to rehabilitate each turtle. Their care costs an average of $15,000.

This year, that would mean spending about a million.

How do you raise enough money for that?

How can you afford not to?

“Saving even one animal’s life could affect things for generations to come,” said Ashley Riese, the vet tech who runs the rehab center.

Threatened yet scrappy, sea turtles ride nature’s waves, so in sync with its cues that they return to the same stretches of shore to lay their eggs. Rhythms disrupted, they become caught in deadly waters.

This year’s hectic season, the turtle team fears, is no fluke.

The Tampa Bay Times followed the turtle hospital over six months as workers sacrificed sleep and missed kids’ bedtimes, gave up critical research and double-stacked turtles in pools. As the turtles kept coming, and coming, the team tried to hold down the front line in a climate emergency.

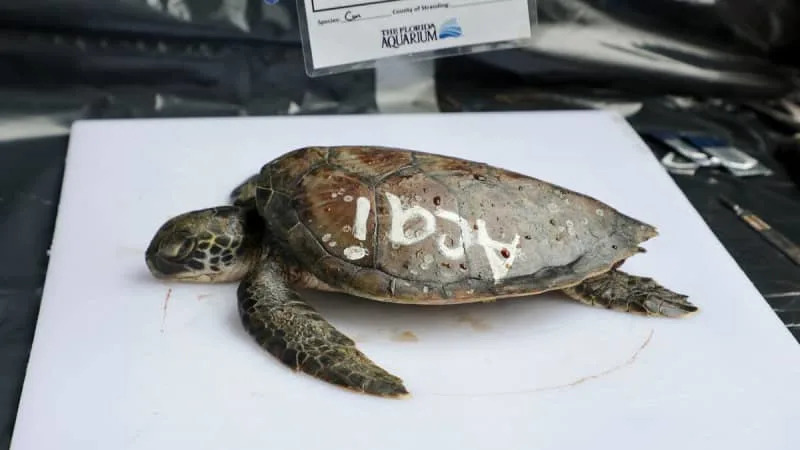

Blue-Gray sprawled on a towel atop a silver scale, his small, oval head lolled to one side. His leathery flippers were ashen and still.

“Cold-stunned, debilitated turtle syndrome,” a technician wrote in Blue-Gray’s chart — the same diagnosis as most.

Status: Endangered

Florida presence: Nests from late winter through summer, mostly along the Atlantic

ID tips: Only sea turtle without scales and a hard shell. Dark, leathery carapace. Average six feet long, often 500 to 1,500 pounds, with long front flippers.

Fun fact:The largest turtle in the world, they’ve been recorded diving more than 4,000 feet deep to eat their favorite food, jellyfish and salps

Top threats:

Accidental capture in fishing gear

Cold affects turtles’ circulation and organ functions. It suppresses their immune systems, which can lead to malnutrition and infections. It damages their skin, shell, even eyes. Barnacles grow on stunned turtles. Predators attack. Some get pneumonia and drown.

Riese, a registered nurse for animals, bent close to Blue-Gray that morning. She estimated that he was about five years old. Turtles don’t mature sexually until they’re about 30, so she couldn’t tell the gender. But she called him a good boy.

She checked Blue-Gray for injuries, drew blood from his neck. She felt his belly, which had collapsed, and opened his mouth to look inside. After shining a light in his hooded eyes, checking for ulcers and perforations, she squirted in ointment and told him to be brave.

“I don’t know if they know we’re helping them,” she told a staffer. “But I hope they know that they’re out of harm’s way with us.”

The hospital sits on the eastern edge of Tampa Bay, near the manatee viewing center and about 20 miles from the Florida Aquarium. The $4 million building opened in 2019, with 19,000 square feet devoted to turtles’ recovery.

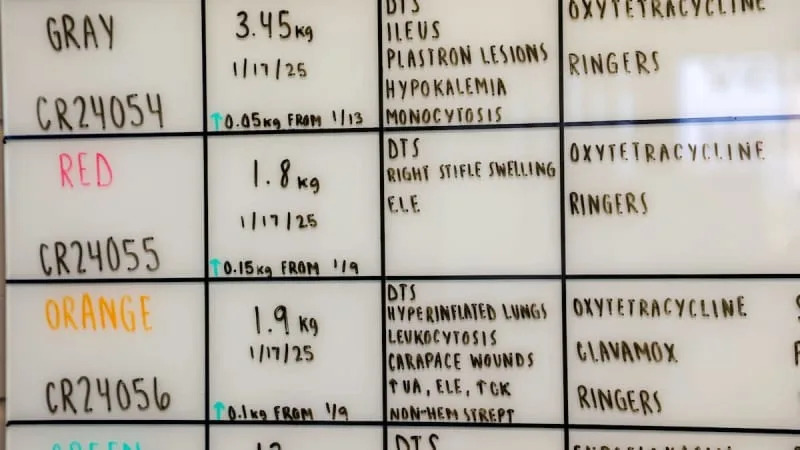

On Thursdays, Riese runs rounds, charting patients’ progress. With colored markers, she tracks medications, meals, therapies, treatments, playtime, poop.

She weaves from the eight portable tanks downstairs to the rehab pools above. She crosses through the commissary, where volunteers portion out shrimp, squid, anchovies, zucchini — and, for picky eaters, salmon and blue crab.

Status: Threatened

Florida presence: Florida’s most common sea turtle nests from April‑September on both coasts

ID tips: Large head with powerful jaws. Reddish-brown, rough shell. Adults reach 275 pounds on average.

Fun fact: Trackers show loggerheads have great stamina, traveling many thousands of miles to feed

Top threats:

Accidental capture in fishing gear

Beachfront development & coastal lighting

Loggerheads, one of the largest species, drift solo in jacuzzi-sized pools. Kemp’s Ridleys, slightly smaller, swim two to a tub.

Past the enrichment center with its foam noodles, green turtles float inside crates that staff built using PVC pipes and plastic lattice. They call these makeshift hospital beds “howdies” and tailor them to each turtle. Vet techs watch to see who sinks, who plays with toys and nibbles lettuce.

In the state’s only deep-dive pool, the team tests buoyancy in 11 feet of saltwater. If a turtle can get to the bottom, it should be able to navigate offshore waters.

Besides the crush of turtles that came in cold-stunned, others had flippers mangled by boat propellers, hooks lodged in their throats, straws stuck in their nostrils, shark teeth sunk in their shells.

A large turtle dubbed Swamp Monster had been immobilized for so long, staff spent hours scraping more than a pound of barnacles off his flippers, face and shell. They had to be careful not to damage the scutes — keratinous scales that protect the shell like a fingernail.

Turtles arrive so sick they all seem the same, vet Lindsey Waxman said. As they start to heal, their personalities emerge.

“I don’t think about why we’re doing this,” Waxman said. “I think: Why not? If not me, who?”

When a turtle is really struggling, workers take shifts by its side, even overnight. Sometimes that means a blood transfusion or a feeding tube. Sometimes an amputation.

Riese, 38, has worked at the Apollo Beach center for nine years. She’s on-call 24/7 and often works 100-hour weeks. A lean, chiseled bodybuilder who won trophies before having kids, she gets up at 3 a.m. to hit the gym — and can still lift a 100-pound loggerhead. She knots her long hair on top of her head, never puts on makeup or paints her nails. She leaves her Crystal Beach home before dawn for the 90-minute commute and usually works through lunch.

Her sons, 9 and 17, say they understand when she has to run out on weekends to pick up a stranded turtle, when she works late and can’t help with homework or take them to hockey practice. The turtles need her.

She’s grateful that her parents and fiancé fill in.

“This job is really a lifestyle,” said Riese, who also has two dogs, a cat and a bearded dragon. “It’s what I want to do.”

Status: Endangered

Florida presence: Nests here occasionally. Juveniles forage offshore, especially in the Gulf

ID tips: Smallest sea turtle. Nearly circular, gray-green shell. Triangular head with slightly hooked beak. Adults grow to 70 to 100 pounds.

Fun fact:They nest in daylight in synchronized patterns, coming ashore in a large group called an “arribada”

Top threats:

Accidental capture in fishing gear

She oversees four staffers and 49 volunteers and works with a team of veterinarians, who split their time with animals at the aquarium.

On the day Blue-Gray came in, veterinarian John Mastrobuono was on call. A former college wrestler, fit and disciplined like Riese, he moved to Florida three years ago with his girlfriend and 8-year-old diamondback terrapin, Beebs. He used to zip the saucer-sized reptile into his backpack for bike rides.

Both land and sea turtles, the vet said, “are pretty emotional, for reptiles.” They have distinct temperaments. Beebs knows his name. “He wants attention and lets you know it.”

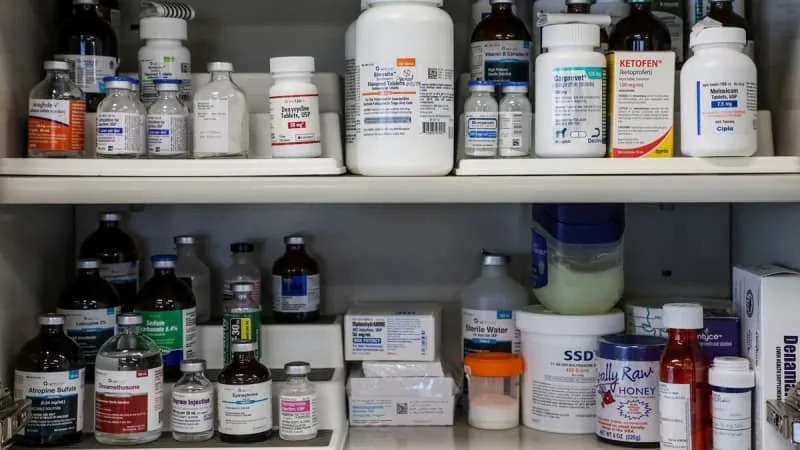

At the hospital, the vet X-rayed Blue-Gray and gave him antibiotics. Riese filled out the turtle’s chart and set him back in his bin.

He seemed better than some of the patients, certainly not among the worst. They didn’t worry about Blue-Gray.

Not yet.

Before staff release a turtle, they clamp a metal tag onto its flipper and slide a microchip into its shoulder. Then they cut off the colored bands. In the surgery suite, clipped tags fill a glass jar — like treasured wristbands from music festivals.

Of 400 sea turtles treated by the aquarium, 380 have gone back into the wild.

“Turtles are the underdogs, just out there eking out a living, trying to stay safe,” said Eric Hovian, an aquarium caretaker. “Then the weather changes, and boom! They get hit hard and end up helpless on the beach.”

To improve turtles’ odds, staffers keep meticulous logs. They perform necropsies on the ones who don’t survive, sending tissue samples to national databases. And they work to better track those who have been let go.

Some loggerheads are big enough to be fitted with satellites, so anyone can follow them through the Sea Turtle Conservancy. Young green turtles are too small, so most of the time, no one knows what happens to them — unless they wash back up.

One turtle the Apollo Beach team released in 2022 came back into their care this year.

If someone sees a turtle with a tag or a wildlife officer scans its microchip, they can follow its journey online and learn where it was caught and released.

Turtles who don’t improve enough to go free live out their lives in captivity.

Visitors to the Tampa aquarium can meet Flip, a 250-pound green sea turtle who has been there for 30 years. And they can swim with Shelldon, a loggerhead about the same hulking size.

They’re the aquarium’s best ambassadors, a way for visitors to see up close the species they could help save.

1,410 cold-stunned turtles rescued in Florida in 2025

66 rescued in Florida in 2024

66 turtles rehabilitated at the Apollo Beach center in 2025

150 million years sea turtles have existed

50 miles a day young sea turtles can swim

$15,000 average cost to rehabilitate one sea turtle

400 sea turtles treated at the Florida Aquarium’s rehabilitation center from 2019 to 2025

10,000 eggs a female lays in her lifetime

One in 1,000 hatchlings survive

On his fifth day at the hospital, a volunteer saw Blue-Gray floating in his tank, listing on his side. He wasn’t paddling.

When Riese scooped him out of the water, his flippers drooped.

His heart rate plummeted on the exam table. He gasped for air.

“His body is shutting down,” Riese told her staff. “He’s giving up.”

Another batch of turtles had come in that week, 18 more from St. Augustine. Now there were 47.

Riese and her staff had spent hours playing “Turtle Tetris,” rotating the animals in and out of pools, doubling them up to make room.

There were turtles in layers of bins stacked in the deep-dive pool. Two turtles in each of the new barrels downstairs.

Staff had been staying late, coming in on weekends. Some aquarium workers shifted over to help at the hospital. Volunteers took extra shifts.

Riese hadn’t had time off in months. Every day, she and a veterinarian examined each turtle, checked its weight, monitored its meals. Each day felt the same — until a new pile of rescues arrived.

Blue-Gray had seemed to be improving, rubbing his shell against the pool, even diving for lettuce. “All the turtle things,” Riese said.

Then, all of a sudden, she said, “he decided to die.”

Blue-Gray was so sick, Riese didn’t have to sedate him to shove a tube into his trachea. He lay still while she performed a sort of turtle CPR.

The turtle was disoriented, dehydrated; his electrolytes were off. So Riese and the vet, Mastrobuono, added another IV line to inject fluids. They took Blue-Gray’s temperature. Drew blood.

Then Riese carried the turtle into the surgery suite to check his organs. She turned him upside down, squirted gel on his belly, scanned it with the wand of an ultrasound machine. On the screen, they saw the problem: Blue-Gray’s intestines were swollen. Something was blocking his digestive system. They added another IV, to flush in medications.

All afternoon, the team worked on the turtle as he lay tethered to drip bags and monitors, his dark shell criss-crossed with surgical tape and tubes.

Maybe extra protein would help Blue-Gray gain strength, they thought. So, on the phone with a pharmacist, they concocted a nutritional supplement to pump through a tube. They tracked the turtle’s breathing, kept tweaking his medications.

When the sky outside the exam room grew dark, Riese texted her sons: “Don’t wait up.” Their dad would have to get them to bed.

The vet and staff stayed, too.

Three hours later, Blue-Gray slowly opened his big eyes. When he tried to flap a flipper, Riese cheered. “You gave us the most worry of everyone,” Mastrobuono told the turtle.

Blue-Gray wasn’t out of the woods. The vet gave him, at best, a 30% chance.

But they hadn’t lost any turtles yet this season. And he seemed stable enough to go back to his plastic barrel for the night.

About 10 p.m., the turtle team finally headed to their homes. Riese couldn’t sleep.

By daybreak, she was back to check on Blue-Gray.

Sea turtles swam with the dinosaurs. They live longer than most animals, some reaching close to a century, and can grow to upwards of 300 pounds.

They’re able to hold their breath for four hours or surface to breathe every 15 minutes. On land, they can survive for half a day.

Some consider sea turtles an “indicator species,” signifiers of the ocean’s health.

In Hindu mythology, a giant sea turtle carries four elephants on its back, and the elephants hold up the globe. If the sea turtle disappears, legends say, the world will end.

Florida, home to five of the globe’s seven species, has more sea turtles than anywhere in the country.

Status: Protected under the Endangered Species Act

Florida presence: Nests here rarely, mainly in Florida’s southeast and Keys from June—August

ID tips: Overlapping scales with a beautiful amber-brown patterning; hawklike beak

Fun fact: An adult eats an average of 1,200 pounds of sea sponges per year

Top threats:

They’ve endured centuries of being caught for their skin and shells, being turned into turtle soup, having their eggs harvested. Over the last 200 years, as fishermen adopted larger nets, sea turtles got tangled — millions dying even when they weren’t targeted.

By 1973, their populations had been so decimated that environmentalists feared extinction — and included sea turtles among the first animals on the Endangered Species Act.

“They’ve survived so much throughout history,” said Luke Sundquist, a biologist at the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. “But development, pollution and climate change are affecting their environments so rapidly — too quickly for them to adapt and respond.”

Condos increasingly cover Florida shores, where nine in 10 U.S. sea turtles nest. A quarter of Florida shoreline is walled off in some way — and counting.

More boat propellers are slicing turtles’ shells and fins, killing about a third of those that wash ashore. One study found that boat strikes in Florida killed about 400 sea turtles over 15 years — mostly in inlets and passes where there was less room to swim away.

Fertilizer run-off poisons lagoons, causing algal blooms that suffocate marine life. A toxic red tide infected both coasts this year. Bacteria, bred by pollution, is giving turtles devastating infections and lesions.

Hotter seas harm coral reefs, where turtles feast. Almost half of U.S. reefs are in “poor” or “fair” condition, suffering from bleaching. Scores are disappearing altogether.

By 2050, one article predicts, sea level rise could inundate more than three-quarters of sea turtles’ nesting grounds.

Warmer sand also means fewer hatchlings survive. And of those who do, who stay in their eggs longer, more turn into females — which skews reproduction ratios.

And hurricanes, with greater intensity, keep hammering their habitat. Back-to-back storms last fall flooded estuaries, shifted sandbars.

Federal funds have never supported sea turtles, like they do dolphins, whales and manatees. This year, lawmakers in Congress introduced an act to help pay for turtle conservation efforts. But it stalled. A single Florida lawmaker signed on.

“There’s just not a lot of funding for sea turtle work and research,” Riese said. “There’s still so much we don’t know about them. The more we learn, the more we can help.”

Along the Atlantic seaboard, and on both Florida coasts, a network of turtle trackers, rescuers and advocates walk beaches searching for nests, wind bright tape around posts to keep people away. Others spend dark nights on the sand watching until hatchlings appear, then, with flashlights, guiding them to the surf.

When a call comes into the rescue hotline, wildlife conservation officers reach out to hundreds of trained volunteers who pick up sick and stranded turtles. The officers then call turtle hospitals, figuring out which has room — and for how many.

Funding can’t keep up.

Some question whether it’s worth $15,000 to save a single turtle.

Others ask: How can you put a price on helping to preserve an entire species, which helps whole ecosystems, which sustain other life?

Sea turtles graze on seagrass, keeping it from overgrowing. They clean coral reefs. Their eggshells feed vegetation that stabilizes dunes.

Each female lays up to 10,000 eggs in her lifetime. A male can fertilize 10 times that amount.

Only one in 1,000 hatchlings survive. But every turtle the team sends back into the water could seed the next generation.

“We’re contributing to the bigger picture, to the future,” Luke said. “We hold the solutions. We just need to be more innovative. I don’t know if we can keep doing this at this rate with the staff we have now.”

The aquarium, a nonprofit, stayed within its $465,000 budget for the hospital and its five staff this year, officials said. (Vets’ salaries come from a different pool.) Admission fees fund about 85% of its operating expenses. Sea turtle license plate sales provided $30,000 for eight emergency room tubs.

The turtle team needs at least two more employees, Luke said, another big recovery pool and more money for the onslaught.

The center’s army of volunteers scrub enclosures, prepare meals, feed turtles with tongs. They help recover dead turtles and release rehabilitated ones.

“It’s hard work, especially at my age,” said Judy Ellington, 72. “But when you can help save an animal’s life, when maybe even one of those will have babies to carry on, that makes everything worthwhile.”

She knows conditions are getting worse, that funding is sparse. That she might not live to see turtle populations recover.

Fewer than 90,000 green sea turtles are estimated to remain worldwide, though their numbers have begun to rebound. This October, an international organization downgraded them from endangered to “a species of least concern.”

Climate change remains a critical threat.

“This is for my grandchildren. And their children,” Ellington said. “It will take a long time, but there will be rewards. It’s like helping make a miracle happen.”

The exam room was stifling. Riese sets the thermostat at 83 degrees to keep the turtles warm. As she hoisted Blue-Gray onto the metal table in mid-March, he smacked her hand with his flipper.

“There you go,” she said, stroking his head. “Do you remember when you tried to die?”

She had moved him from the emergency tub near her office into a larger barrel downstairs. He was eating fish pockets packed with pills, playing with PVC puzzles, basking beneath the faucet to feel the waterfall massage his tiger-striped shell.

More turtles had kept flooding in. Turtles from Patrick Space Force Base and Port Orange, more from St. Augustine. Now, there were 56 — the most at once since the hospital opened. Everyone had to share a pool.

Two, by then, had died.

Some of the patients were starting to come out of their shells. Red, who’d been strangled by fishing line, was sassy, nipping at her handlers. Pink, missing a flipper from a shark attack, was no longer swimming in circles; she’d become feisty, head-butting her howdie when people came close. Purple-Purple seemed less stressed, starting to stretch his back flippers and glide across his enclosure.

Gray, one vet said, was “the nicest turtle we’ve ever had. He lets you do anything to him.” He even seems grateful, the vet said, looks you in the eye.

After several variations of food supplements, Blue-Gray was eating lettuce and shrimp, gaining weight. His infection seemed to have cleared. But Riese kept him on antibiotics just in case.

“We’re not supposed to have favorites,” she told him as she took his temperature. “But you gave us such a fright and have come such a long way.”

She keeps photos of Blue-Gray in her phone, alongside her sons.

One spring afternoon, while Riese and Luke were checking turtles, a school group stopped outside the exam room.

Some kids seemed bored, checking their phones. Others pushed to the front of a wall-sized window, pressing their hands against the glass.

“Hi everybody!” Luke waved. She picked up the turtle on the table, carried it closer, its tummy toward the crowd. A microphone broadcast her voice outside.

“This is Yellow-Yellow,” Luke said, holding out his flipper. “See his bands?”

Most of the fifth-graders from Seffner Elementary had never seen a sea turtle. Some took pictures.

“These turtles are very sick,” Luke said. “They got cold, so we’re taking care of them.”

Education is a big part of the hospital’s purpose. If you can get kids to fall in love with turtles, they’ll want to help save the ocean, Luke said, maybe even the whole earth.

A 7-year-old girl from Pennsylvania wrote Riese a letter saying she wanted to grow up to be her. Another started a sea turtle club at her middle school.

“People feel overwhelmed, like they can’t make a difference,” Luke told the students. “But you don’t have to change everything in your life. Just do what you can, set an example, make a donation, volunteer.”

All the turtles should have been gone by late April, back into the open water.

Riese and her team should have been spending their days on boats, scooping healthy turtles from the Gulf, gathering data to track long-term trends.

Last year, they examined 100 turtles in the wild.

This year there was no money — or time.

“I have no idea what we’ll do next year,” Luke said. “We didn’t budget for all this. We’re still caring for too many turtles.”

Nine had been released.

That left a staggering 55 turtles that still needed help. “They’re getting more energetic,” Luke said. “But they’re not all ready.”

Riese and her staff remained holed up in the hospital, enlarging pens, moving patients from shallow to deeper pools.

Four months after washing ashore, Blue-Gray paddled around, diving and surfacing, chasing his roommate, Light Blue-Pink. When the vet, Mastrobuono, loaded him into a tub to wheel him to the exam room, Blue-Gray tried to clamber out.

“Whoa there,” the vet said, pushing him back. “Look at you go!”

As the vet set Blue-Gray on the scale, he whipped his head sideways, snapping at the vet’s wrist. Mastrobuono laughed. “You were our problem child,” he told the turtle. “I guess we did our job.”

When they try to bite you, he said, you know they’re better.

To be released, turtles’ blood work has to show no signs of infection. They have to be eating well and prove they can dive deep.

Riese recorded Blue-Gray’s weight: 11 pounds. He had gained three. His concave belly had rounded. “My little football,” she said, smiling.

The turtle’s intestines, lungs and heart were clear. When the vet shone a light in his eyes, he followed it. When Riese felt his flippers, he smacked her. “Oh, you’re so strong,” she said.

Blue-Gray had been off antibiotics for a week. If he stayed healthy for the next month, he might get to go home.

On a warm, sparkling morning in late May, Blue-Gray scuttled in a plastic tub in the aquarium van.

The turtle team decides who’s ready to return to the water. Fish and wildlife officials determine when and where. They don’t do releases on weekends or holidays — too many people. They don’t let them go near dredge sites, beach nourishment projects or busy resorts. They watch the weather and tides.

And they try to return the turtles as close as possible to where they had stranded. Sea turtles know where they came from.

After recovering from respiratory failure and an intestinal blockage, getting medications and therapy for nearly five months, Blue-Gray would be let go about 80 miles south of where he was found.

At Ormond Beach, volunteers unspooled blue twine, outlining a path to the ocean’s edge.

Seagulls screamed through the cloudless sky. The salt air was sticky, almost summer.

A few yards down the shore, plastic ribbons framed a sea turtle nest. A sign of hope.

“This is going to go very fast,” Luke told a crowd of about 100 who had gathered to watch.

Somehow, staff had survived the hospital’s busiest season yet. They were exhausted, anxious to spend time with their families. Maybe even get back out on the water to resume their research.

But they still had too many patients, 25. And more could arrive any time: Hurricane season was three days away.

The future seemed scary.

Six years ago, when the rehab center opened, it treated 16 turtles.

This year, it admitted 66.

For Riese and her team, it’s one turtle at a time.

They want their patients to remain wary in the wild. But after months of watching them come back to life, grow and play and bite, “It’s hard not to become attached,” Riese said.

“The first few times, I was like a mom sending her kids off to school,” she said. “I couldn’t stop thinking about them: Where are you? What are you doing? Are you OK?”

Now, she and Luke said, the send-offs are just sweet. Not bitter.

As the sun climbed over the Atlantic, staff lugged 10 bins to the beach and lifted out each turtle for Riese to examine one last time. Then they carried the kicking animals in front of them and lined up between the twine.

“The waves are strong today,” Riese warned. “Get them out over the breakers before you release them so they don’t get washed back.”

She carried Blue-Gray herself, hoisting him high, like a trophy.

“Alright, big guy, don’t get hit by a boat. Don’t get entangled in fishing gear. Watch out for predators. Live a long, healthy, happy life. Make lots of babies. Lots and lots. I hope we never see you again.”

Staff waded in until the surf lapped their waists. The crowd cheered. Riese waited for a gap between the waves, then lowered Blue-Gray into the warm water and gave him a push.

The turtle paddled away, dove into the dark sea. Riese watched until she saw him resurface. Then, suddenly, Blue-Gray turned around and raised his right flipper.

Riese laughed.

Maybe he was steadying himself, getting his bearings before heading home.

Riese would rather think he was waving goodbye.

Learn more

If you see a sick or dead sea turtle, call the FWC Hotline: 888-404-3922

Visit the Apollo Beach

Donate to or volunteer with the Florida Aquarium’s Sea Turtle Conservation Program

Visit sea turtles in Tampa at The Florida Aquarium

Track turtles who have been tagged and released at Sea Turtle Tracking

Follow the state’s Sea Turtle Program at myfwc.com/wildlifehabitats/wildlife/sea-turtle/

About the story

This story is based on six months of reporting and research by Tampa Bay Times staff writer Lane DeGregory and photojournalist Douglas Clifford.

During the state’s busiest-ever sea turtle stranding season, they followed veterinarians, volunteers and staff at Florida Aquarium’s Sea Turtle Rehabilitation Center who were struggling to save a record number of rescues.

The opening scene was reconstructed through interviews and documents; so was the scene when Blue-Gray’s health plummets.

The Times witnessed turtle intake at the hospital and attended rounds, therapy, examinations and more throughout the winter and spring. The journalists watched the release at Ormond Beach.

To understand the science behind the strandings, the Times interviewed wildlife specialists and veterinarians, conservationists and aquarium executives and reviewed journal articles, studies and reports.