The idea of changing Broward County’s name to Lauderdale County is still alive — but it’s in big trouble.

Opponents came forward Thursday, most significantly from state lawmakers who represent the county, and from county commissioners.

They raised multiple objections, including:

The cost of making the change.

The optics of making the change when some residents are feeling tough times.

Whether it makes sense to replace “Broward,” named for someone with controversial racial views, with “Lauderdale,” who is controversial for his involvement in removing Native Americans from their ancestral lands.

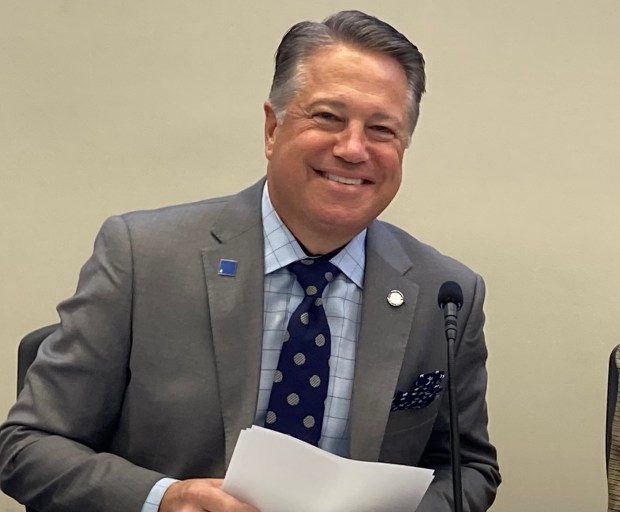

Legislation sponsored by state Rep. Chip LaMarca, a Broward Republican, would ask the county’s voters in November 2026 if they want to change the county’s name from Broward to Lauderdale.

It was headed for defeat on Thursday, with a majority of Broward Legislative Delegation members who participated in a hearing in Fort Lauderdale on local legislative priorities for 2026 declaring their intention to vote no.

The measure was rescued from defeat by state Rep. Robin Bartleman, a Democrat who chairs the delegation. She promised LaMarca that she’d schedule a future hearing to give his bill another chance if he agreed to withdraw it, for now, from consideration.

He agreed — and expressed frustration with his colleagues.

Several legislators said they didn’t want to advance the measure for action in Tallahassee before getting a sense of whether the Broward County Commission supported asking voters about a name change. The answer came hours later.

Commissioner Michael Udine, who has been championing the renaming referendum idea along with LaMarca, withdrew his resolution that would have declared official commission support after it became clear it would lose.

A majority of county commissioners said it was premature because they didn’t have enough information about the costs, benefits, and other questions. Udine said he might — or might not — bring it back for consideration in the future.

The Legislative Delegation hearing on the bill was unusual.

It was long, lasting more than an hour. So-called local bills usually sail through delegation hearings and get forwarded to Tallahassee for action by the full Legislature. (The delegation is made up of all senators and representatives whose districts include at least part of the county).

It was also unusually contentious, with legislators sometimes expressing irritation with one another — even though several professed their admiration and respect for LaMarca. (“Highly respected,” Bartleman said. “I love Chip,” said Democratic state Sen. Rosalyn Osgood. “Everybody here adores Representative LaMarca,” declared Republican state Rep. Hillary Cassel.)

Support and opposition didn’t break along party lines. Several Democratic legislators supported it; several opposed it. The delegation’s two Republicans also were split.

Cost was the main area of contention for state legislators.

Poll: Would you vote to change Broward County to Lauderdale County?

LaMarca estimated the cost of the change, if approved by voters, as “roughly at or under $10 million,” the first time supporters of the idea provided an estimate.

Several legislators said it was a mistake to consider spending that kind of money at a time when many people are struggling to make ends meet — and at a time when the state Legislature is considering proposals that could lead to massive property tax cuts that could force county governments to cut services.

State Rep. Marie Woodson, D-Hollywood, said many young people can’t afford first homes and many seniors are deciding between paying for medicine or food. “Do you think right now this is an issue we need to focus on?”

LaMara said it was possible to do multiple things at once. “You made a lot of good points about things that I care about, too, but I think we can walk and chew gum at the same time.”

Cassel said she didn’t think it was a wise use of money. And she said the $10 million cost estimate wasn’t realistic, that it would certainly be far higher. She estimated it would cost $25 million to $50 million “when you look at all the kinds of things that have to be changed.”

Later, County Commissioner Nan Rich, an opponent of the idea, said it would cost “millions and millions and millions” of dollars.

State Rep. Michael Gottlieb, D-Davie, scoffed at his colleagues’ focus on the $10 million cost.

He said it would be spread over several years and that it was a pittance to pay for the economic benefits he and LaMarca said could flow from the renaming.

“It’s a complete red herring to say it’s going to cost $10 million. It’s going to cost $10 million over seven years,” Gottlieb said. “But if they are correct that it’s going to bring in more money, then the cost is really irrelevant. You can’t grow without spending some money to grow.”

LaMarca said it was not something that would require spending all at once.

It would take place over time, and some things would be replaced as they wear out anyway.

“To be very clear, it’s not, ‘go out tomorrow morning and make this change,’” LaMarca said. “We’re sitting talking about the pennies of making changes in something like this where we’re talking about playing at a major league level with our counties in the north and south.”

State Rep. Chip LaMarca, a Broward Republican, at a hearing of the county legislative delegation on Oct. 27, 2025, at Memorial Regional Hospital in Hollywood. LaMarca is sponsoring legislation that would place a referendum on the ballot in 2026 asking Broward voters if they want to change the county’s name to Lauderdale. (Anthony Man/South Florida Sun Sentinel)

State Rep. Chip LaMarca, a Broward Republican, at a hearing of the county legislative delegation on Oct. 27, 2025, at Memorial Regional Hospital in Hollywood. LaMarca is sponsoring legislation that would place a referendum on the ballot in 2026 asking Broward voters if they want to change the county’s name to Lauderdale. (Anthony Man/South Florida Sun Sentinel)

LaMarca and leaders of the Broward Workshop, an organization of the executives from the county’s top businesses who have been pushing the change, said it would lure businesses to relocate in Broward instead of Palm Beach or Miami-Dade counties, and would help the county attract even more tourists.

LaMarca predicted the name change would produce $200 million in economic benefits every year.

“It boggles the mind that we’re talking about … over the course of almost a decade to spend a few million bucks on rebranding when I’m telling you that we’re talking about hundreds of millions of dollars in return on investment from investment in our community,” LaMarca said.

State Rep. Marie Woodson, D-Hollywood, asked LaMarca could cite any studies that show “just by changing the name of the county it would stimulate an economic impact?” LaMarca said he didn’t. “I’m looking to our neighbors to the north and south of us,” he said.

State Sen. Tina Polsky, a Democrat whose district includes parts of Palm Beach County and northwest Broward, was skeptical of the purported $200 million. “How do we know any of that and how do we know that one name is better than another name?” Polssy said.

LaMarca said the issue was about creating a global brand and image for the county, which would produce economic benefits, and pointed to a “white paper” from the Broward Workshop describing benefits.

LaMarca said that Miami-Dade and Palm Beach counties “are globally known brands. To remain competitive and visible, we should stand beside them, not beneath them.”

He promised “a lot better data” would be provided before any action in Tallahassee — if the bill makes it that far.

Cassel read a long list of things that would require name changes. And Bartleman, a former School Board member, cited several potential costs to the school district — “I feel like this is an unfunded mandate for public schools” — including the markings on school buses.

That led to one of the examples of friction during the discussion. LaMarca shot back with a note of sarcasm that the name Broward or Lauderdale on school buses was not a major issue. “If we’re going to think about a single vinyl decal lettering change on yellow school buses, I’ll go help them put the stickers on the buses,” he said.

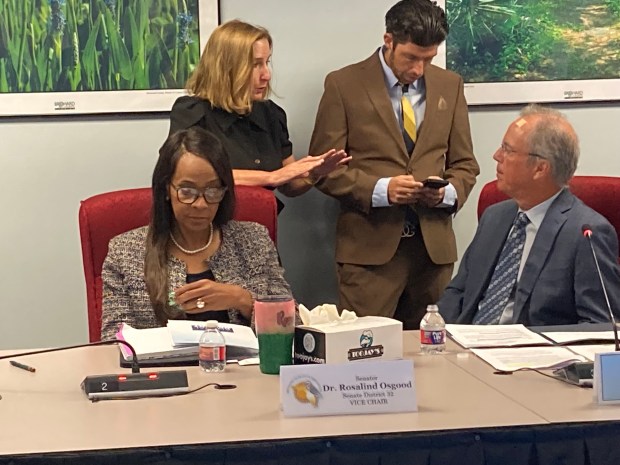

State Sen. Rosalind Osgood, seated at left, state Rep. Robin Bartleman, gesturing, and Broward Mayor Beam Furr, opposed efforts to quickly move forward with plans to support a referendum asking voters if they want to change Broward County’s name to Lauderdale County. (Anthony Man/South Florida Sun Sentinel)

State Sen. Rosalind Osgood, seated at left, state Rep. Robin Bartleman, gesturing, and Broward Mayor Beam Furr, opposed efforts to quickly move forward with plans to support a referendum asking voters if they want to change Broward County’s name to Lauderdale County. (Anthony Man/South Florida Sun Sentinel)

Worthy names?

State Sen. Rosalind Osgood, D-Fort Lauderdale, said she had a far different concern. If a renaming is to be considered, she said, there should be alternatives to the county’s namesake, Napoleon Bonaparte Broward, or to the proposed alternative, William Lauderdale.

Broward County was named after Napoleon Bonaparte Broward, who served as the state’s 19th governor in the early part of the 20th Century.

Broward has long been known, and criticized, for the draining of parts of the Everglades to create land for agriculture and development. But about a decade ago, new information came to light after a researcher discovered text of a speech Broward delivered to the Legislature in 1907 that revealed segregationist views and his call for creation of a separate country for Black people.

Lauderdale, the namesake of several cities in Broward, arrived at the New River in South Florida where he established a fort in 1938. He was a major, leading the Tennessee Volunteers was a key figure in the forced removal of Native Americans from their ancestral lands.

“Napoleon Bonaparte Broward really hated Black people. He thought that we should locate to another territory. If it was left up to him, I wouldn’t even be able to live here at all,” Osgood said. “And Mr. Lauderdale, who was just so racist and with his mistreatment of indigenous people, it’s just we’re caught between two evils.”

If there’s a renaming, Osgood suggested, it should be part of a discussion that opens it up to a historical figure who wasn’t racist. She suggested Eula Johnson or W. George Allen, both civil-rights activists who were leaders in the movement that led to the desegregation of Fort Lauderdale beach in the 1960s.

Dwight Bullard, a former state senator and state representative who is now senior political adviser for the left-leaning Florida Rising organization, was one of three people members of the public who spoke at the delegation meeting.

“These folks have a very, very troubled history in terms of their violence, both committed against indigenous as well as people of color,” Bullard said. “And so whether it is Broward, who I hate to say was a racist, or Lauderdale, who also was a racist, it’s probably in your best interest to probably let sleeping dogs lie.”

The renaming has only gotten attention in recent weeks. Broward Workshop leaders have been advocating for it in meetings with commissioners. No proponents or opponents signed up to speak before the commission on Thursday.

Commissioner Steve Geller said he had a town hall meeting attended by a small group of constituents on Wednesday.

Everyone who attended opposed the idea. County Mayor Beam Furr said he’s been hearing from fellow graduates of South Broward High School who raised questions about changing the name Broward.

Two people besides Bullard, both opponents, addressed state legislators.

“Drive through any place in Broward County, and all you see is construction cranes,” said Patti Lynn of Tamarac, voicing skepticism that businesses aren’t relocating to the county. “Why put an extra burden on us, the taxpayers of Broward County, to pay for this. It’s just not necessary.”

Jennifer Jones of Sunrise said it was “extremely out of touch to bring this up when there is an affordability crisis, when there is a housing crisis. … With all due respect, shame on you.”

Thursday was supposed to be the last scheduled meeting of the Broward Legislative Delegation before the beginning of the 2026 legislative session.

Lawmakers have several days scheduled in Tallahassee next month. After consulting with delegation staffers about the required timeframes for advertising and complying with legislative timeline rules, Bartleman said she would schedule another hearing, most likely on Dec. 5, at which LaMarca would get another chance to advance his legislation.

The statue of Napoleon Bonaparte Broward on the third floor of the Broward County Courthouse was removed in 2017. (Mike Stocker/South Florida Sun Sentinel)

The statue of Napoleon Bonaparte Broward on the third floor of the Broward County Courthouse was removed in 2017. (Mike Stocker/South Florida Sun Sentinel)

Community identities

Five of Broward’s cities, towns and villages have Lauderdale or a derivation in their names: Fort Lauderdale, Lauderhill, Lauderdale Lakes, North Lauderdale and Lauderdale-by-the-Sea.

The 26 others don’t.

Geller said before moving forward he’d want a clear indication of the sentiment from the leaders of the five cities he represents — none of which have Lauderdale in their names — before deciding whether to support or oppose a renaming.

Mayor Dean Trantalis of Fort Lauderdale, the largest city in the county, said he hasn’t talked to other mayors, but thinks many would not like the idea.

“It kind of emasculates a lot of the other cities in the county by kind of taking away their identity, where the name Lauderdale kind of swallows up the rest of the county,” he said.

Trantalis said he understands why the county might want benefits from the Lauderdale brand, but is skeptical it would achieve what its proponents are seeking. “Rebranding the county name is not the solution to achieving greater awareness.”

Trantalis, who has had some differences with county leaders on major policy issues, said a rebranding would do less to benefit the community than a reorganization of government to give Broward a directly elected mayor. That idea has been floated and died in the past.

But Mayor Angelo Castillo of Pembroke Pines, the second-most-populous city in the county, said he doesn’t object to the idea.

“For the most part, when you say Broward County to people up north, they all know Florida, they all know Fort Lauderdale, but they don’t know Broward,” said Castillo, who has lived in South Florida for 30 years after living for 36 years mostly in New York.

“If this will brand us better in ways that make us more prosperous, stronger, better in ways that we can enjoy, not just now, but into the future, I see no reason why we shouldn’t,” Castillo said.

Staff writer Rafael Olmeda contributed to this report.

Political writer Anthony Man can be reached at aman@sunsentinel.com and can be found @browardpolitics on Bluesky, Threads, Facebook and Mastodon.