A large metal box lies far off the public trail in a New Port Richey wilderness preserve, tucked away.

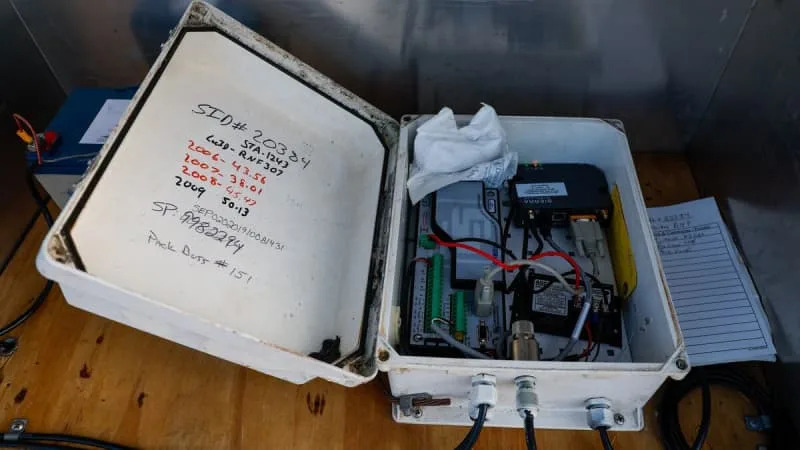

The box holds equipment used to record data for a rainfall gauge— one of 171 across the Southwest Florida Water Management District’s 16 counties.

It’s unassuming, and not particularly exciting.

That is until Everett Eldridge, the district’s hydrologic data field technician supervisor, unlocked the box Monday to reveal a plump cockroach wriggling around inside.

“That’s common out here,” Eldridge said, unbothered.

What you really have to look out for are the wasps that nest under the metal. Or the snakes that curl up inside (nonehave been venomous), he said. Or the scorpions, like the one that stung him at a Hillsborough rain gauge.

Eldridge can’t say he’s been to all 171 of the district’s rain gauges, but he’s been to most of them in his 21 years with the district.

This month, the rain gauge in the Starkey Wilderness Preserve has recorded 0.15 inches of rain — on par with the rest of the water management district, where most locations have not recorded even half an inch of rain. The rainfall information is one set of data used by the district to make decisions on the region’s water supply.

“All the rainfall we get, it trickles down into the aquifer, and that’s where all of our drinking water comes from, so it helps to understand how much water we’re receiving,” Eldridge said.

Across Florida, nearly 8 million people are under drought conditions, according to the National Integrated Drought Information System. In Tampa Bay, most of the area is under a moderate drought — a “D1” on a scale that runs from “D0” to “D4.”

In northern areas of the state, residents are under an extreme drought (D3), and a small percentage are under an exceptional drought (D4).

During a moderate drought, streams and reservoirs are typically low, crops can be damaged and water shortages could be in the future, according to the National Weather Service.

Earlier-than-normal dry conditions took hold in September, said Stephen Shiveley, a meteorologist for the National Weather Service’s Tampa Bay office.

The period from Sept. 1 to Nov. 16,when a little more than an inch of rain fell, was the driest on record in Tampa. On average, about 10 inches fall within that timeframe, according to weather data.

During a November governing board meeting, the water district said the area was running at a 13-inch rainfall deficit compared to the average yearly total.

During that meeting, the board placed much of the district under a“Phase 1 water shortage”beginning Dec. 1 and running through July 1.

Residents can still water twice weekly unless the city where they live has stricter watering policies. The phase requires local utilities to review and carry out methods for water conservation.

Over the past few years, the Tampa Bay area has seen rainfall extremes on both sides of the spectrum.

In 2023, it was the driest rainy season in 26 years.

Then, last year, Tampa had its wettest year on record, buoyed by rainfall from the hurricane season.

According to Tampa Bay Water, the surge of rainfall from hurricanes Helene and Milton helped sustain the region through inconsistent rain.

“Without the river flow that resulted from the hurricanes, we would have needed water from the reservoir during much of the year to sustain production from our surface water treatment plant,” Tampa Bay Water wrote in a blog post overviewing the 2025 fiscal year.

Florida saw no tropical activity this year. It’s a big win after a disastrous 2024 hurricane season, but it meant less rainfall than typical during the area’s wet season.

The benefit of a drought is that less rainfall means less water flowing into the estuary, which carries nutrients thatcan lead to algae blooms.

In 2023, waters were crystal clear, but last year’shurricanes mucked up water quality.

“We’re certainly not seeing the kinds of water clarity that you would expect with drought, because we’re coming off such a wet season last year, and then we have actually had wet months this year,” said Maya Burke,assistant director of the Tampa Bay Estuary Program.

While Florida is typically considered a wet, humid state, drought is quick to descend. In the Southeast, a combination of high temperatures and little rain means water can evaporate faster, leading to dry soil — a key drought indicator, according to the drought information system.

Climate change appears to be leading to more severe droughts in the Southeast, according to the Fifth National Climate Assessment.

“If you zero in on these smaller time steps, what we’re seeing is changes in the timing and delivery of rainfall,” Burke said.

“It’s kind of like feast and famine within seasons.”

A seasonal drought outlook from the National Weather Service’s Climate Prediction Center shows that much of the Tampa Bay area is likely to see the drought persist through winter.

The globe is currently experiencing a weak La Niña, one part in a cycle that affects weather across the globe. La Niña is likely to continue for the next few months, which typically leads to less rain and higher temperatures in Florida winter, Shiveley said.

On Monday, Eldridge locked up the rain reporting equipment in New Port Richey.

Next to it, the cylindricalrain gauge is propped up high. Inside, a little silver bucket tips back and forth when rainwater trickles through. For 1 inch of rain, it tips 100 times.

For the foreseeable future, the mechanism is not likely to get much use.

• • •

The Tampa Bay Times launched the Environment Hub in 2025 to focus on some of Florida‘s most urgent and enduring challenges. You can contribute through our journalism fund by clicking here.