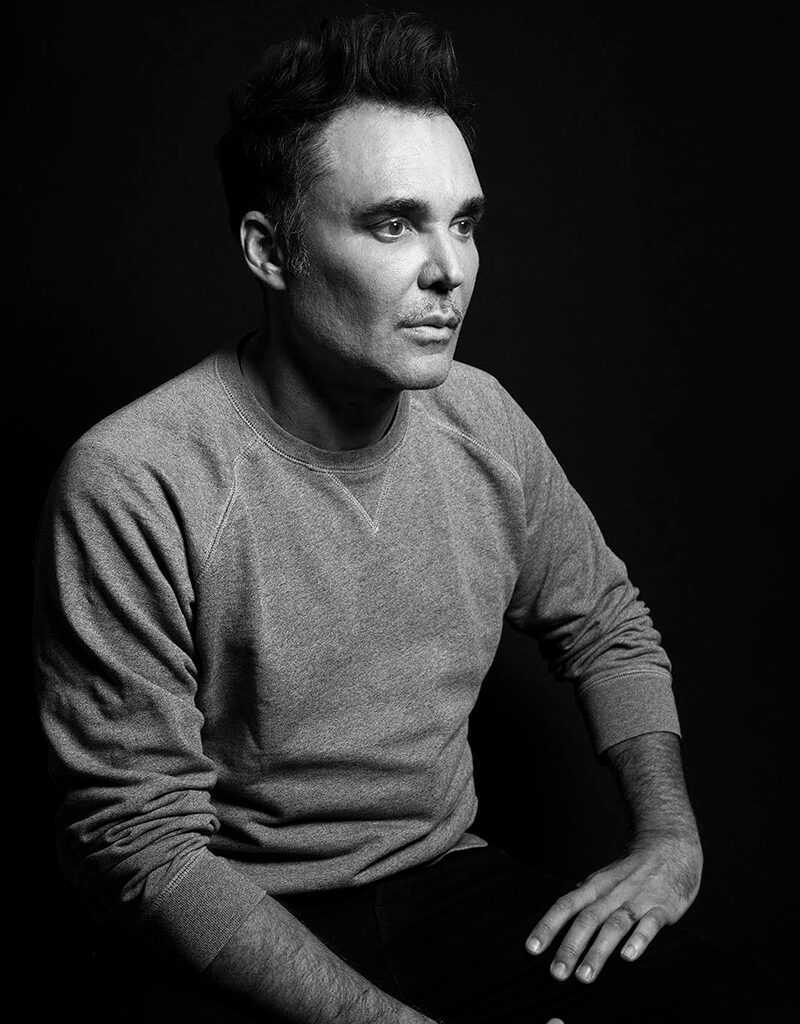

Photo Credit: Luca Pizzaroni

Photo Credit: Luca Pizzaroni

Miami in December feels like a fever dream. The traffic on Collins Avenue slows to a crawl, private jets crowd the tarmac, champagne flutes clink on rooftop terraces, and everywhere you turn, there’s the hum of anticipation: what to see, who to spot, what moment will define Art Basel this time. And this year, David LaChapelle’s apocalyptic vision is part of that fever pitch. On December 5, inside VISU Contemporary, the acclaimed photographer will open Vanishing Act, a landmark exhibition featuring over 30 works from his career, including the world premiere of nine new pieces. For the Bruce Halpryn-owned-and-curated boutique gallery — a bold newcomer with growing presence in Miami’s art scene — hosting an artist of LaChapelle’s caliber for his second major Miami exhibition is both a profound honor and a strategic coup. It signals that Miami’s art infrastructure has matured beyond the fair itself, and that the city can support serious contemporary art year-round, not just during the annual December frenzy. Yet, for LaChapelle, who first arrived in the city in 1984 — twenty years old and freshly dispatched by Andy Warhol to photograph the emerging South Beach scene for Interview magazine — it’s a homecoming.

But what he’s bringing back isn’t nostalgia. LaChapelle has been photographing the end of the world for 33 years, and Vanishing Act is both retrospective and warning — a visual archive of everything we’ve built, everything that’s disappeared, and everything still at risk. That forward focus is evident in Vanishing Act. These aren’t images about past glories or lost golden ages. They’re about now, about the crisis we’re living through, about the vanishing act currently in progress. “Vanishing Act — the title of the show — comes from this new chapter that we’re living in the world,” LaChapelle explains. “I think we all feel it. If we’re conscious, you know, if we live long enough, we’ve definitely seen that we’re in a different chapter than we were previously, that something feels very different in the world.” And so, the title refers not to LaChapelle’s own disappearance from the mainstream art world, but to the larger disappearance — of species, of coastlines, of the stable climate that allowed human civilization to flourish.

That apocalyptic vision has deep roots. Born in Connecticut in 1963, he’d attended the North Carolina School of the Arts, originally enrolling as a painter. Even then, he was developing the analog techniques that would define his career — hand-painting his own negatives to achieve a sublime spectrum of color before processing his film. The process was meticulous, almost meditative: working in the darkroom’s red-lit solitude, applying transparent oils and dyes directly to the negative with brushes so fine they had only a few hairs, building up layers of color that would transform when light passed through them during printing. Each stroke had to be considered, permanent. There was no undo button, no layers palette. Just his hands, the negative, and the knowledge that this intervention would fundamentally alter how the image appeared in the world. It was painting and photography married together, a hybrid medium he was inventing as he went. At 17, he’d moved to New York City with little more than ambition and a portfolio. His first photography show at Gallery 303 caught Warhol’s attention, and the job offer followed.

Ocean Drive in 1984 was not yet the neon-lit runway it would become. The hotel where he stayed cost eleven dollars a night. South Beach was where people went when they’d run out of other places to go — retirees on fixed incomes, Cuban refugees, artists who couldn’t afford New York, hustlers and dreamers and people hiding from something. LaChapelle photographed all of it: the drag queens and club kids, the faded hotels, the sense of a place suspended between what it had been and what it might become. He couldn’t have known he was documenting the last moments before the transformation, before the money arrived and turned South Beach into a global brand.

In those fleeting moments of photographic capture, LaChapelle was unknowingly absorbing Warhol’s most profound lesson: that transformation is itself an art form, and that the most extraordinary revelations emerge from carefully observing the seemingly mundane. The camera, like Warhol’s artistic vision, could transmute the ordinary into something transcendent, turning a neighborhood’s liminal state into a canvas of potential and possibility. “Andy took the everyday object and elevated it to fine art,” LaChapelle recalls. “He made me realize that a photograph can change the way you see things.”

That lesson stuck. But where Warhol found his subject in Campbell’s soup and Brillo boxes, LaChapelle would eventually turn his lens toward larger game: the collapse of civilization itself, rendered in the same supersaturated colors and meticulous staging that made his celebrity portraits iconic. The kid Warhol sent to Miami would spend the next four decades building a body of work that functions as both spectacle and warning, entertainment and elegy, a visual record of a collapse that spans from 2012 to the present.

At its center is Vanishing Act, a series of images that reveals him not as a trend-chasing commercial photographer who occasionally makes art, but as an artist with a sustained, evolving vision of planetary catastrophe.

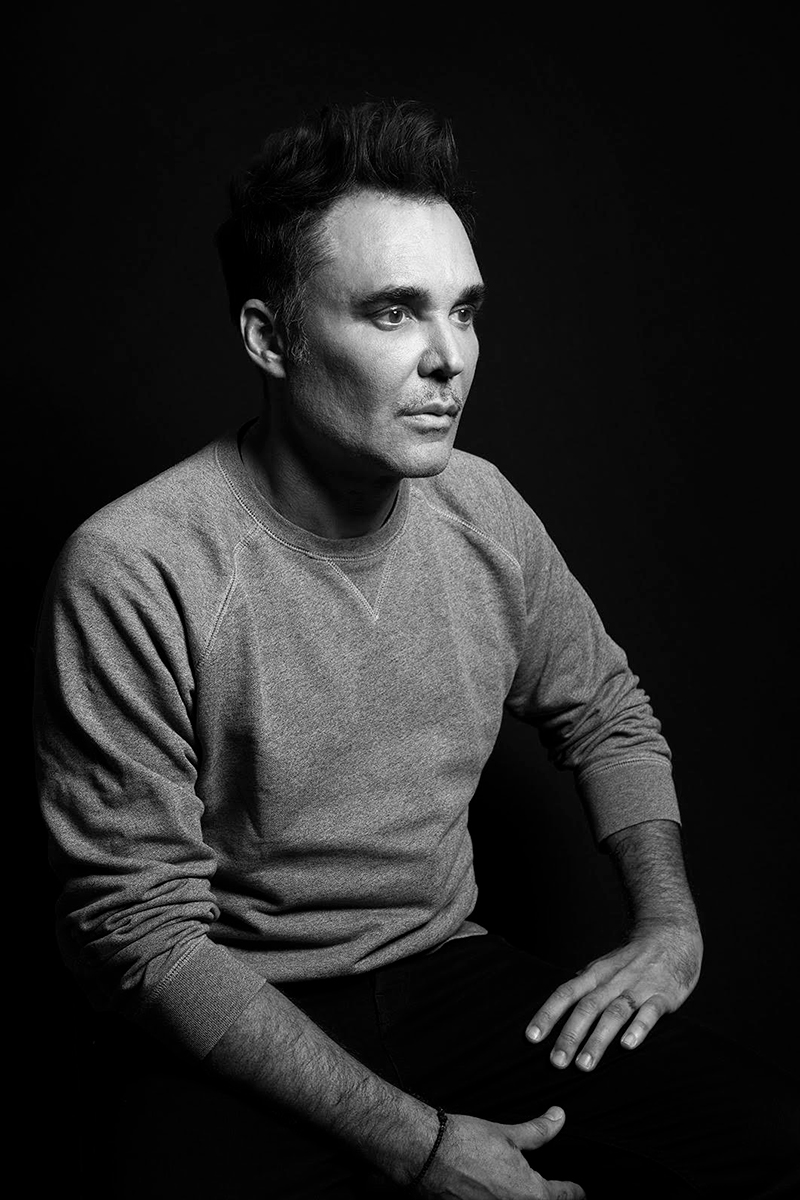

Photo Credit: Thomas Canet

Photo Credit: Thomas Canet

It begins with Seismic Shift in 2012: a gas station submerged in floodwaters, the pumps still standing like tombstones, everything rendered in LaChapelle’s signature hyperreal color palette. The image is beautiful and terrible in equal measure, a postcard from a future that was already arriving.

Two years later came Aristocracy (2014), where a classical mansion crumbles into the sea, and Gas (2014), which pushed the flooded station imagery further into the realm of the sublime. In the Gas series, nature doesn’t just reclaim the abandoned stations — it explodes through them in a riot of green. Vines snake up the pumps like they’re strangling them. Trees burst through concrete, their roots cracking the forecourt into geometric fragments. Flowers bloom from the cash register. The fluorescent lights still glow underwater, casting an eerie turquoise light through the murk, illuminating schools of tropical fish that swim where customers once stood. It’s post-apocalyptic, but it’s also strangely hopeful — a vision of what happens when the human world fails and the natural world rushes back in to fill the void. These weren’t one-off provocations. They were chapters in an ongoing narrative, each image building on the last, each one refining the visual language of catastrophe.

Then came Spree in 2020, and the timing turned prophetic. He completed Spree just days before Covid-19 lockdowns and no-sail orders took effect. The image shows a massive cruise ship — a symbol of mindless consumption and environmental excess — listing in turbulent waters, its decks empty, its lights still blazing in defiance of the chaos around it. It’s a party that doesn’t know it’s over, a celebration on the Titanic.

The timing was uncanny. Within weeks, actual cruise ships would become floating quarantine zones, plague ships denied entry to ports around the world, their passengers trapped in cabins as the virus spread through recycled air. LaChapelle’s image suddenly looked less like fantasy and more like documentary, less like warning and more like evidence.

Now, in 2025, he’s returned to that cruise ship image with Will the World End in Fire, Will the World End in Ice, the newest work in the series and one of the exhibition’s world premieres. The image splits the difference between its titular extremes: the cruise ship is simultaneously engulfed in flames and encased in ice,

a physical impossibility rendered with such technical precision that your brain accepts it even as your logic rejects it. The fire is theatrical, almost biblical, tongues of flame that rise in perfect columns against a sky gone dark with smoke. The ice isn’t the white of glaciers but a deep, unnatural blue, crystalline structures that have grown over the ship’s hull like a disease. The vessel itself is caught mid-tilt, frozen in the moment before it goes under, its windows still lit from within — someone’s still home, still partying, still refusing to acknowledge what’s happening. The water around it churns with an energy that suggests both boiling and freezing. It’s Robert Frost’s poem made literal, the end of the world delivered in both fire and ice simultaneously. The progression from Seismic Shift to this latest iteration traces not just the evolution of LaChapelle’s technique, but the acceleration of the crisis itself. What felt like distant warning in 2012 now reads as present-tense emergency.

Another world premiere series, Negative Currency (1990-2025), operates on a parallel track. Inspired by Warhol’s One Dollar Bill silkscreens, LaChapelle spent 35 years photographing currency from nations in economic collapse. The bills are shot against black backgrounds and backlit, transforming them into luminous objects that glow like stained glass windows in a cathedral of failed economies. The newest additions feature bills from Cuba, Venezuela, and North Korea — paper that represents value in theory but functions as evidence of failure in practice. The

Photo Credit: Thomas Canet

Photo Credit: Thomas Canet

Venezuelan bolivar note glows an almost supernatural orange, its denomination so inflated it’s essentially meaningless. The North Korean won is rendered in shades of pink and green, the portrait of Kim Il-sung staring out with an expression that reads differently when you know the bill can’t buy anything. The Cuban peso, with its image of Che Guevara, becomes a ghost of revolutionary promise, backlit until the paper itself seems to dissolve, leaving only the image floating in darkness. Each bill is beautiful in isolation, but together they form a catalog of collapse, a numismatic record of what happens when the social contract breaks down and the paper we agreed to believe in reveals itself as just paper.

The series connects to the environmental work through a shared concern with systems in collapse, whether ecological or economic. Both explore what happens when the promises printed on money or implicit in our relationship with the planet turn out to be lies we told ourselves.

Also premiering in the exhibition is Tower of Babel (2024), LaChapelle’s meditation on communication breakdown and human hubris. The image reimagines Bruegel’s famous painting as a contemporary construction site — a massive skyscraper rising from floodwaters, its upper floors still under construction, cranes frozen in mid-lift. But the building is already crumbling at its base, the foundation dissolving even as workers continue building higher. The sky behind it roils with storm clouds that have that particular LaChapelle quality of being both real and hyperreal. Construction workers in hard hats and safety vests populate the scaffolding, but they’re not looking at each other, not communicating — each one isolated in their own task, building toward a collective goal that’s already doomed. It’s a vision of our current moment: still building, still reaching higher, even as the ground beneath us gives way.

The spiritual works in the exhibition offer a different kind of intensity. Annunciation (2019) reimagines the angel Gabriel’s visit to Mary as a contemporary scene: a young woman in a modest apartment, light streaming through the window in shafts so defined they look solid, and the angel rendered not with wings but with an aura of light so intense it bleaches out the details, leaving only a human-shaped radiance. Our Lady of the Flowers (2018) shows a figure — gender deliberately ambiguous — standing in a field of flowers that seem to glow from within, each petal rendered in colors that don’t quite exist in nature, the whole scene suffused with a golden light that suggests both sunset and something more transcendent. The Sorrows (2021) depicts a pietà for the modern age: a figure cradling another in their arms, both dressed in contemporary clothes, surrounded by the detritus of modern life — plastic bottles, discarded electronics — but lit with the same reverent light Caravaggio used for his religious scenes. He is using spiritual iconography to offer clarity, meaning, and transcendence amid contemporary chaos.

“I don’t want to add confusion to the world,” LaChapelle says. “I want to be very clear on what I want to communicate to people.”

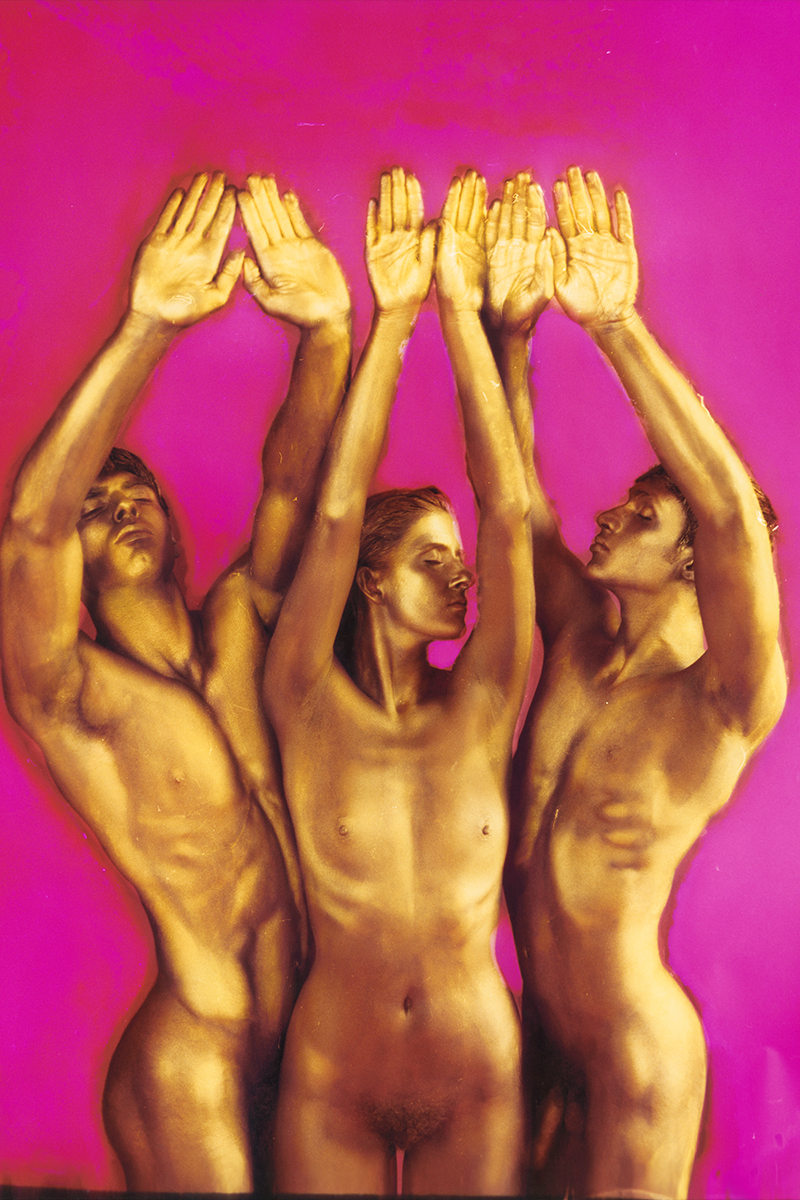

DAVID LACHAPELLE, EXHIBITION, 1997

DAVID LACHAPELLE, EXHIBITION, 1997

Photo Credit: VISU Gallery

The clarity comes through in the work’s refusal to look away. These aren’t abstract meditations on decline. They’re specific, material, grounded in the physical reality of flooded cities and worthless paper. LaChapelle’s maximalist aesthetic — often dismissed as mere excess by critics — serves a purpose here. The beauty is the point. It makes you look at what you’d rather ignore.

His process remains defiantly analog in an age of AI-generated imagery and digital manipulation. His elaborate sets are built by hand, populated by real bodies, and constructed like stage productions, complete with costume designers and art directors and the organized chaos of opening night. That early technique he developed in art school — hand-painting negatives to achieve impossible colors — was just the beginning of a lifelong commitment to physical craft.

“What I do is very theatrical, so it lends itself very easily,” he says. “Shoots to me are like stage productions and it’s your opening night. We work towards these shoots, we set up the tableaux, we cast it and costume and photograph it. It’s like the curtain goes up and then people usually clap when the picture’s done.”

But the theatricality isn’t artifice for its own sake, he’s quick to point out. It’s a method of creating images that exist in physical space before they exist as photographs. “I’m capturing this thing that did actually exist in time,” LaChapelle insists. “It wasn’t created on a computer screen. It was created with hands and human beings.”

His commitment to material reality gives the work a weight that purely digital imagery often lacks. When you look at a LaChapelle photograph, you’re seeing evidence of an event that actually occurred, a moment when dozens of people collaborated to build something that existed for just long enough to be captured on film. The image is a document of that collective effort, that shared vision.

DAVID LACHAPELLE, MEGAN THEE STALLION: POETIC JUSTICE, 2022

DAVID LACHAPELLE, MEGAN THEE STALLION: POETIC JUSTICE, 2022

Photo Credit: VISU Gallery

“The goal has always been to make pictures like music, and to touch people with them the way that music does,” he explains. The analogy is apt. Music exists in time, requires performance, demands the coordination of multiple elements into a unified whole. So do LaChapelle’s photographs, even if the performance lasts only as long as the shutter stays open.

That shutter seemingly never shuts. His lens has captured everyone from Madonna and David Bowie to Tupac and Whitney Houston, from Elizabeth Taylor to Lady Gaga, from Dua Lipa to Travis Scott. These images — collected in books like LaChapelle Land (1996), Hotel LaChapelle (1999), Heaven to Hell (2006), Lost & Found (2017), and Good News (2017) — became the template for how celebrity would be photographed in the age of maximum spectacle. His work then expanded beyond still photography into music videos, film, and stage projects. In 2005, his feature film Rize, documenting the krumping dance movement in South Central Los Angeles, was released theatrically in 17 countries, proving his vision could translate across mediums.

But there’s always been tension between that commercial success and his deeper spiritual concerns, he admits.

“The pictures that I did for myself are very, very spiritual,” he says. “And that’s how I started in the eighties, back when I was a kid. I was doing pictures of angels and I was questioning where my friends were going — they were all dying really young of AIDS. And I feel that same urgency again in the world right now.”

That urgency has sharpened his critique of contemporary culture. He’s particularly troubled by the entertainment industry’s obsession with true crime and serial killers. “I think Netflix has been glorifying serial killers; it’s the most-watched genre,” he observes. “But these are people’s lives, these are people who have suffered, some of whose families are still alive. And this kind of pain should not be entertainment.”

It’s a pointed comment from someone who has spent decades working in entertainment, who has helped create the visual vocabulary of celebrity culture. But he’s always positioned himself as something other than a simple mirror of the culture he documents. “It’s like instead of a mirror, it’s more of a prism to just take the light and refract it into all the different colors,” he explains. The prism doesn’t just reflect — it transforms, reveals hidden spectrums, breaks unified light into its component parts.

His spiritual work has found an unexpected audience among LGBTQ+ communities, particularly in Latin America. His images of angels and religious ecstasy, his unabashed embrace of faith without judgment, have resonated with those who were told they had to choose between their identity and their spirituality.

“A lot of times I’ll go to a show in Mexico City and there’s a lot of gay kids and trans and drag queens and everybody’s in the same line because they didn’t realize that they could be gay or could be dressed in drag or like Beyoncé or whatever, and still have God in their lives,” he says.

The connection extends to his ongoing work with musicians like Jake Wesley Rogers, whose visual aesthetic draws heavily on LaChapelle’s fusion of the sacred and the profane, the spiritual and the sexual. For these audiences, LaChapelle’s work offers permission — to be fully themselves without abandoning the transcendent, to find divinity in places the mainstream church refuses to look.

Financial independence has allowed him to follow his vision without compromise, and he’s unflinchingly frank about the role money has played in artistic freedom. “I was really just praying for a cabin in the woods because I feel close to God there, and to be able to afford vegetarian food and to be able to support myse

DAVID LACHAPELLE, GLORIFY, 1986

DAVID LACHAPELLE, GLORIFY, 1986

Photo Credit: VISU Gallerylf as a photographer,” he recalls. “That was really what I prayed for and that was answered. And then some.”

That “and then some” has funded two decades of living off-grid in Maui, where he’s built a life far from the celebrity circus that made him famous. It’s the opposite of one of his celebrity photo shoots — no assistants, no stylists, no clients, no deadlines. Just him and the work he wants to make, the images that matter regardless of whether they’ll ever run in a magazine or sell to a collector. The studio is separate from the house, a space where he can spread out works in progress, where prints can dry and ideas can develop at their own pace. When he does travel for commercial work — a celebrity portrait session in Los Angeles, a campaign shoot in New York — the contrast is stark. He moves from total solitude to controlled chaos and back again, using each to fuel the other. The distance isn’t retreat — it’s strategy. It allows him to work on the long-term projects that matter to him, to develop series like the environmental collapse images over years and decades rather than chasing the next magazine cover or advertising campaign.

The commercial work still happens, but it serves the personal work now, not the other way around. He’s inverted the usual relationship between art and commerce, using his marketability to fund his vision rather than letting market demands shape what he creates.

Twenty years off-grid in Maui has also given him perspective on the New York art world he left behind. He’s not interested in nostalgia, even for the legendary 1980s downtown scene where he got his start.

“We could just stay in the past. New York was so great in the eighties. I have friends from the 80s in New York who felt that was the highlight of their life, and they talk about that time often,” he says. “But I’m still looking at today.”

That forward focus is what Vanishing Act demands. Not a retreat into what was beautiful, but an insistence on finding beauty in what remains. In his case, that means photographing it — the light that’s still here, the bodies that still move, the faces that still believe.

“Yes, we’re in a new chapter, but there’s still so much beauty left,” he says. “We don’t have to give in to the darkness and confusion.”

It’s a discipline he’s maintained through four decades and 40 countries, through five major books and exhibitions at the Musée d’Orsay, the Victoria and Albert Museum, and Fotografiska, and one that earned him the Lorenzo il Magnifico Lifetime Achievement Award at the 2023 Florence Biennale. The accolades accumulate, but they’re not the point. The point is the work itself, and what it might do for whoever stands in front of it.

And that leads us back to the beginning, back to Miami, with the launch of his latest exhibition — during Art Basel —mere weeks away. On December 5, the doors to VISU Contemporary will open. Collectors and novices, art students and tourists, will all move through the same space, pausing before the same images. A cruise ship suspended between fire and ice. Currency that glows like stained glass. Angels and flowers and bodies bathed in light that feels both otherworldly and achingly human.

LaChapelle has been trying to show us the end of the world for the duration of his career. At this point, explanation feels beside the point. His invitation now is simpler, borrowed from Philip trying to convince Nathanael that the Messiah had arrived: “Come and see.”

Photo Credit: Thomas Canet

Photo Credit: Thomas Canet