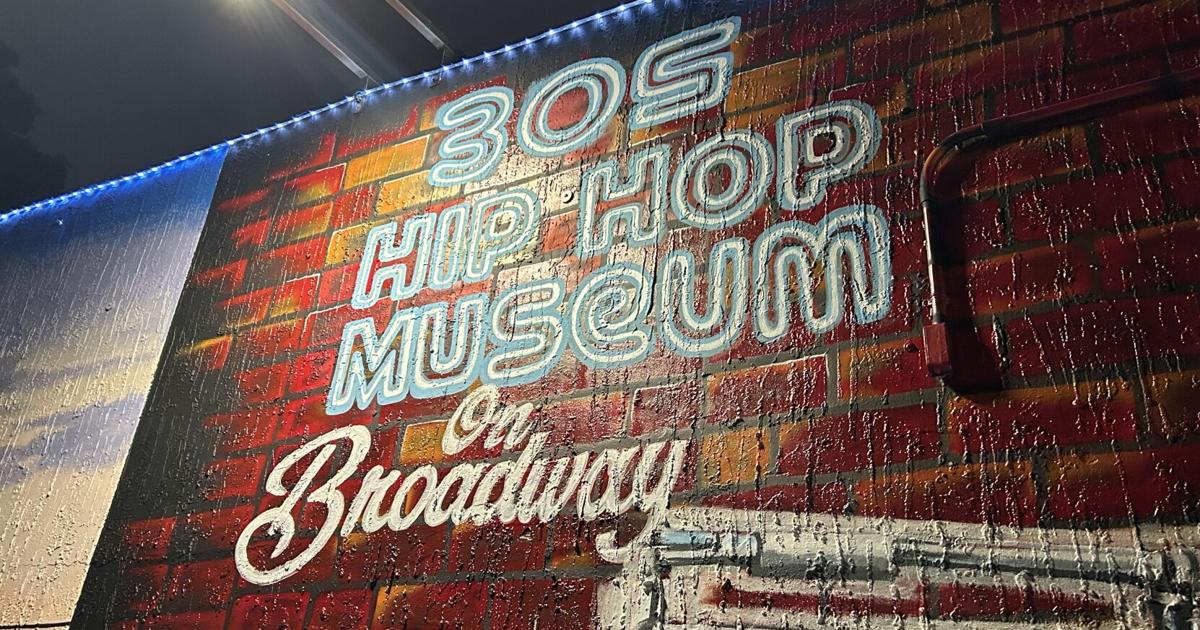

On the eve of Miami Art Week, two men ushered in the opening of Liberty City’s very own hip-hop museum Saturday, dedicating the space to the art form’s long-standing legacy in the Magic City.

The 305 Hip-Hop Museum was born out of a collaboration between local entrepreneur Broadway Harewood and artist Marvin Weeks in an effort to preserve one of Black history’s greatest cultural touchstones while pushing back against those that would diminish it.

“What inspired me to do this was when our governor said he was going to get rid of Black history,” Harewood said about the DeSantis administration’s controversial education policies. “Why would I allow our governor to just delete history when I was a part of it? That means he’s deleting me, and I didn’t feel comfortable with that.”

Portraits of Miami hip-hop icons line the wall.

(Rafael Hernandez for The Miami Times)

Beyond honoring local legends like 2 Live Crew and Denzel Curry, the team behind the museum hopes it will be a place where everyone in the community can gather and learn, bridging the gap between older hip-hop aficionados and the newer generations all the while.

The museum sits within the Broadway Musical Art District, founded by Harewood and later enhanced by Miami-Dade County Commissioner Keon Hardemon’s placement of street signs honoring hip-hop’s top 100 artists.

A painting depicts rap and hip-hop legends.

(Rafael Hernandez for The Miami Times)

The district’s centerpiece is a building wrapped in murals depicting hip-hop legends, with a back wall dedicated to those who’ve passed.

Revitalizing a neighborhood

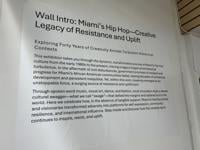

A wall of text describes the museum’s purpose and mission.

(Rafael Hernandez for The Miami Times)

Harewood’s vision extends beyond preservation, seeing the museum as a catalyst for his neighborhood’s transformation.

Since purchasing his first property on the block in 1987, he’s steadily acquired up to 85 properties, transforming an area once known for its troubles into a safe space where he believes everyone can feel secure.

Broadway Harewood celebrates the building’s opening as the DJ blasts music.

(Rafael Hernandez for The Miami Times)

“This is like one of the most safe streets you could ever be on,” Harewood said. “A lot of people don’t know how safe our neighborhood is. It’s not like it used to be back in the ‘80s.”

For Weeks, the museum’s opening was a long time coming. He became involved in the initiative to create an arts district in the neighborhood in 2015, aiming to change Liberty City’s checkered reputation by showing off the talent of its residents.

Antawn Chinn shares his hand-drawn artwork.

(Rafael Hernandez for The Miami Times)

As the former chairman of the City of Miami Arts and Entertainment Council, Weeks brought his promotional expertise to the project. Now, with its completion, he hopes it will bring the change he’s aiming for.

“It’s about hoping we can blend and have a place where residents and people can be proud of safety, elimination of drugs, vices, and violence,” he said. “We want to make this become a neighborhood where people of all kinds can come and partake in the culture.”

A record player along with records from Miami hip-hop stars adorns a table.

(Rafael Hernandez for The Miami Times)

Weeks hopes visitors will come away from the exhibits believing in their own artistry and ready to channel it like the people before them once did.

“People use creativity to develop themselves where the government failed,” Weeks said, referring to the 1980 Arthur McDuffie riots. “They’ve always used creativity, whether it’s music, art, dance, performances to change their lives.”

Derrick Days performs at the opening event.

(Rafael Hernandez for The Miami Times)

The museum’s opening also doubled as a homecoming for Derrick Days, a rapper who performed during the event.

Having grown up in Liberty City, Days sees the building as something he wished the neighborhood had during his childhood. Now that its doors are officially open, the only place he sees the museum going is up.

Marvin Weeks, along with Harewood, thank everyone who attended the opening festivities.

(Rafael Hernandez for The Miami Times)

“Two, three years from now, it depends on what we put into it. It could be a studio on top where people can actually record, or a dance hall or something,” said Days. “I’m looking forward, it can expand for the youth. The youth can get an idea of what culture really is and, you know, they can actually embed it in their hearts so they can be able to be more productive.”

A cultural touchstone

Coming back to Liberty City was more of a literal journey for Avery Delaval, who flew from Tanzania to help Harewood assemble the museum’s exhibits and art installations.

Having spent the last four years out of the country, Delaval was reminded of hip-hop’s global influence when last year’s feud between Kendrick Lamar and Drake reached his notice even on an entirely different continent.

“Watching on the internet, and seeing just the world reacting, including Africa, and seeing the song take off everywhere, and seeing the power of the culture — that was powerful, being in the continent but seeing my culture like everywhere in the world,” Delaval said.

For Delaval, hip-hop is an art form that anyone can partake in and contribute to, but it will always remain a foundationally Black touchstone. And, he says, places like the hip-hop museum will help people from all cultures understand the genre’s history in Miami from the African American perspective.

“Somebody might be from Venezuela and don’t understand the culture of 18th Avenue, or what the history of this place is,” Delaval said. “There’s definitely a true culture of the area, so people should be aware of it and know about it.”