Photo Credit: Nick Garcia

Photo Credit: Nick Garcia

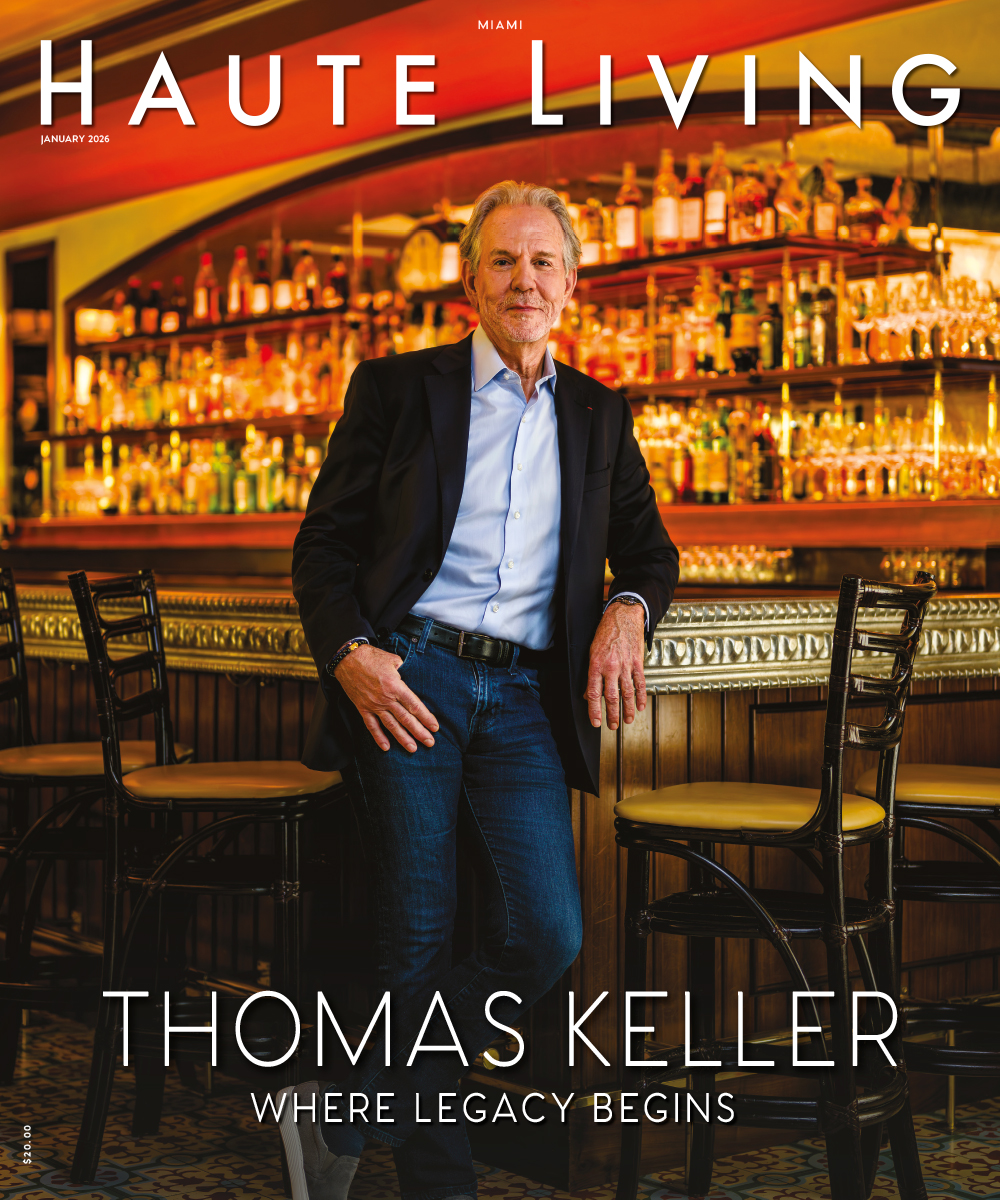

Thomas Keller once swore he’d never return to South Florida. The region of his youth, as he recalls, “wasn’t a place like it is today — there wasn’t a lot of culinary opportunity for me in the early ‘80s.” But decades later, the French Laundry and Per Se icon has come back — not just to open restaurants, but to build community. With The Surf Club Restaurant and now Bouchon in Coral Gables, Keller is rewriting Miami’s culinary future in the very place he once left behind.

It’s a homecoming decades in the making, and one Keller himself never anticipated. When he left South Florida in the early 1980s to pursue his culinary ambitions — first in New York, then France, then back to New York, and finally California — he did so with a sense of finality. There simply wasn’t the infrastructure, the culture, or the opportunity for a young cook with grand ambitions. “I swore I would never go back to Florida,” he says now, with the clarity that only hindsight affords. The region that shaped his earliest years in the industry had no place in the vision he was building for himself. So he moved on, and for years, he didn’t look back.

What he built in the decades that followed redefined American fine dining. Keller became the first and only American-born chef to hold multiple three-star ratings from the prestigious Michelin Guide — a feat that positioned him alongside the world’s most elite culinary talents. His accolades read like a roll call of the industry’s highest honors: The Culinary Institute of America’s “Chef of the Year,” the James Beard Foundation’s “Outstanding Chef” and “Outstanding Restaurateur” awards, honorary doctorates from Johnson & Wales University and The Culinary Institute of America. France itself recognized his contributions, designating him a Chevalier of The French Legion of Honor — the first American male chef to receive the distinction. He led Team USA to its first-ever gold medal at the Bocuse d’Or, the biennial competition regarded as the Olympics of the culinary world. And, with more than 1.6 million copies of his cookbooks in print, including the recently released The French Laundry, Per Se, Keller isn’t just a chef: he’s an institution.

But South Florida changed. And so did Keller’s relationship to it. The turning point came through friendship — a persistent one. A close friend who visited him regularly at The French Laundry kept urging him to reconsider. “He would always say, you need to come back to Florida,” Keller recalls. “And I would always brush aside the idea, thinking I’m not coming back to Florida.” Until the Surf Club opportunity emerged. Even then, he resisted — until he visited the property and discovered its history. Suddenly, the idea of returning didn’t feel like a concession. It felt like destiny.

The Surf Club Restaurant wasn’t just another luxury hotel project. It was one of the most legendary social destinations in the world during the 1940s and ‘50s, a magnet for high society, debutante balls, and Old Hollywood glamour. “The whole history of the Surf Club fascinated me,” Keller says. It was the perfect home for his TAK Room concept — a continental cuisine restaurant rooted in the kind of elegant, old-world establishments his mother managed when he was a child. The concept had already been refined through multiple iterations aboard Seabourn cruise ships, but The Surf Club Restaurant became its first land-based expression. “There would be no better place to launch TAK Room than at the Surf Club,” he reflects. The name stayed, honoring the property’s storied past, but the soul of the restaurant was unmistakably Keller’s: precise, evocative, deeply American yet shaped by European influence.

Seven years later, The Surf Club Restaurant remains a cornerstone of Keller’s South Florida presence — a restaurant that has not only endured but thrived. And now, with Bouchon in Coral Gables, he’s deepened his roots in the region, this time with a concept built entirely around community.

“For me, Bouchon has always been a community restaurant,” Keller explains. “I really wanted to make a connection with the community in Coral Gables and those individuals there — making sure that we embed ourselves in these locations where friends, families especially, and colleagues can get together to enjoy a great meal and a great environment.” It’s a philosophy that distinguishes Bouchon from his three-Michelin-star temples like The French Laundry and Per Se. This isn’t about haute cuisine theatrics or tasting menu pyrotechnics. It’s about something more timeless: the French bistro, rendered with integrity and warmth.

The location itself was part of the attraction. Bouchon occupies La Palma, a historic building dating back to 1928. “I’m always attracted to historic locations,” Keller says. There’s a reverence in his voice when he talks about these spaces — places with memory, with soul, with stories etched into their walls. For Keller, restaurants are never just venues. They are custodians of culture, and the buildings that house them matter as much as the food that emerges from their kitchens.

Inside, every detail evokes the spirit of a Parisian bistro: the materials, the colors, the lighting, the energy. “We wanted to establish that through its design elements,” Keller says. “The way it feels, the energy that’s created there — it’s all about being representative of a French urban bistro.” But while the aesthetic channels Paris, the ethos is unmistakably Keller’s. The menu is rooted in classic French bistro cuisine: onion soup, pâté, roasted chicken, lamb, escargot, an oyster bar. These are dishes with deep cultural roots, but they’re executed with a modern sensibility — lighter, healthier, more thoughtful about sourcing and technique. “Modern cuisine is much lighter, certainly much healthier, in terms of what we’re able to produce,” he notes. “But it is a French bistro, and we wanted to establish that.”

The team assembled to bring this vision to life is as carefully curated as the menu. Chef de cuisine Garrett Rochowiak came from Bouchon in Yountville. Executive sous chef Neil Ybarra arrived from Las Vegas. General manager Erin Rouchi and maître d’ William Hoff anchor the dining room, alongside beverage director Michel Couvreux. “Between the four of them, and Michel who works at Bouchon quite often, they’re a significant part of that restaurant and how we interact with our neighbors and our friends,” Keller says. “That’s really the most important thing about building a restaurant in Coral Gables.” It’s a close-knit team, bound by shared values and a collective commitment to hospitality. For Keller, that’s not incidental — it’s foundational.

But Bouchon isn’t just about preserving French tradition. It’s also about honoring the relationships that make that tradition possible. Keller speaks with deep admiration about the farmers, fishermen, foragers, and gardeners who supply his restaurants — many of whom he’s worked with for decades. Keith Martin at Elysian Fields Farm has been supplying lamb to Keller’s restaurants for years, raising the animals holistically. “We want to represent France in its glory,” Keller says, “but we’re always modernizing it with our ingredients and our techniques.” It’s a delicate balance: respecting the past while embracing the present, honoring tradition while pushing it forward.

There’s a brunch at Bouchon Las Vegas that regulars speak about in near-reverential tones. The same attention to detail, the same devotion to craft, defines the Coral Gables location. It’s not about reinvention for its own sake. It’s about consistency, excellence, and the quiet pleasure of a meal done right. “A French bistro is what it is,” Keller says. “But we want to represent it in its entirety and not have deviations as many restaurants do these days. You know, a twist on this or a twist on that. We wanted to represent France in its glory.”

Photo Credit: Nick Garcia

Photo Credit: Nick Garcia

For Keller, the decision to open two restaurants in South Florida wasn’t just strategic — it was personal. “Having two restaurants in one location helps me when I visit South Florida,” he explains. “Rather than having restaurants in different cities or different locations around the country, I prefer to consolidate my efforts in a location which I really believe in. And as you know, South Florida is a location that I truly believe in.” The Surf Club Restaurant has been open for seven years. Bouchon in Coral Gables is still establishing itself. Together, they represent not just an expansion of Keller’s empire, but a homecoming — a return to the place that once felt too small, now reimagined as grounds for legacy-building.

But Keller is quick to note that success isn’t measured solely in revenue or accolades. “We’ve been very happy with the quality of the work that our teams are doing to produce great food, wonderful service, and a beautiful environment, and giving our guests great memories,” he says. Memories — that word comes up again and again in conversation with Keller. For him, the ultimate metric of success isn’t a Michelin star or a packed reservation book. It’s whether a guest leaves with something lasting. “Success for me is not about fame and fortune,” he says. “Success is about giving people memories. If you can give somebody a memory that lasts — that’s a lifelong, life-lasting memory. And that experience will be with them until the day they die. That’s a beautiful thing to think about: the impact that we have on others.”

It’s a philosophy shaped, in part, by the lessons his mother imparted when he was young — lessons he still carries with him. “What my mother taught me as a young person in South Florida has been with me my entire life,” Keller reflects. “Dedication to the craft of what you’re doing. Paying attention to the details. Always paying attention to the details. Never, never giving up.” That last phrase — never give up — is something of a personal mantra. It appears on his golf hat. It’s woven into the way he approaches his work. “If you give up, then there’s no opportunity to move forward,” he says simply. “So never give up. Continue to move forward.”

Those lessons have served him well, particularly during the inevitable setbacks. Keller is candid about the challenges he’s faced, including the closure of Bouchon Beverly Hills after eight-and-a-half years. “It’s a difficult thing, especially for me, because I get really emotionally attached to my restaurants and, more, emotionally attached to the teams that are there and being able to support them in their endeavors and their goals,” he says. Losing a restaurant isn’t just a business loss — it’s personal. But even in those moments, the lesson his mother taught him holds: keep moving forward.

These days, Keller spends most of his time at home in Yountville, where The French Laundry remains the beating heart of his culinary universe. He’s there about 280 days a year, often in the restaurant for hours at a time — sometimes the entire day. “What interests me is my team,” he says. “Being able to interact with the young chefs, the young dining room team, and just share examples of what we do and how we do things and really how easy it is to make people happy. A smile on your face when they walk in the door. Giving them great service and good food. Listening to them. Giving them an opportunity to engage in conversation — not just the mechanical, robotic kind of system, but actually something they get emotionally attached to and developing memories for people.”

For Keller, hospitality is the soul of the work. “Service is number one, always,” he insists. “Food is number two or number three in some of these memories and experiences. I’ve told my team for decades that service is number one. Being able to give great service — people will always come back. Giving great food with poor service, people won’t come back.” It’s a conviction born from decades of observation, refinement, and an unwavering belief that restaurants are, at their core, about human connection.

That connection extends beyond the dining room. Keller draws surprising parallels between cooking and golf — two pursuits that, on the surface, seem worlds apart. “Cooking to me is a lot like golf,” he explains. “There are many similarities. It’s a process. It takes time. The transformation of food is the most interesting part — the process of braising beef, roasting a chicken. These things take focus, attention, preparation, time, patience, and persistence to result in something beneficial to you and your guests. That’s the same with golf.” Both demand attentiveness. Both reward practice. Both require you to be fully present. “I’m totally immersed in the moment,” Keller confides. “I can’t be thinking about other things when I’m standing over a golf ball, and the same way I can’t be thinking about other things when I’m cooking.”

And somewhere in that practice of presence, his understanding of time shifted. For Keller, it has become the ultimate luxury — and the ultimate teacher. “Time is something we take for granted in different parts of our lives. And then, as we start to mature and get older, we realize that time is the most important thing, and the choice of what you’re going to do with that time is even more critical. Making sure that you’re really thinking about what you want to do, executing on that, and being successful in using your time wisely.” It’s a hard-won wisdom, the kind that only comes from years spent mastering a craft, building a legacy, and learning what truly matters.

Behind him in his office hangs a wall full of awards — plaques, trophies, certificates from a career that has redefined American fine dining. Among them: his James Beard Foundation honors, his Chevalier designation, reminders of that Bocuse d’Or gold medal. But Keller is quick to contextualize them. “Those are all things I did yesterday,” he says. “Any accolade that you receive today is for what you did yesterday. And so all of this stuff here is literally behind me — metaphorically, they’re behind me. I just want to move on.” It’s a striking sentiment from someone who has achieved so much: the refusal to rest on laurels, the insistence on forward motion, the belief that the best work is always still ahead.

Photo Credit: Nick Garcia

Photo Credit: Nick Garcia

And yet, for all his focus on the future, Keller is deeply concerned with the present — specifically, the fragility of the restaurant industry and the importance of supporting the people who make it possible. “If you want good restaurants in your community, you have to support them,” he says with urgency. “There are so many young chefs, so many young restaurateurs who really struggle. They’re only busy Thursday, Friday, and Saturday night, and the rest of the week they’re struggling to make payroll. We need — if we want restaurants, if we want really good restaurants — we have to support them. We have to pay for them. We have to be committed to visiting them. Otherwise, you’re not going to have good restaurants. It’s just that simple.”

It’s less about “if you build it, they will come,” and more about “if you support them, they will stay.” For Keller, the longevity of a restaurant depends not just on the chef’s talent or the quality of the food, but on the community’s willingness to show up, to invest, to care. “Good restaurants aren’t just going to come to your community because you want them to,” he says. “They’ll come to your community because you’re supporting them.”

That ethos — community, commitment, connection — is what defines Keller’s return to South Florida. The Surf Club Restaurant and Bouchon aren’t just restaurants. They’re gathering places, landmarks, institutions in the making. They’re spaces where memories are forged, where strangers become regulars, where the act of breaking bread becomes something transcendent. And they’re proof that sometimes, the places we leave behind are the ones we’re meant to return to — not as we left them, but as we’ve become.

In South Florida, Thomas Keller has come full circle. The region that couldn’t hold him in his youth now anchors a new chapter of his legacy — one built not on accolades, but on presence. On showing up. On nurturing a community that, decades ago, he swore he’d never see again. It’s a homecoming earned through perseverance, shaped by time, and rooted in the belief that great restaurants aren’t just places to eat. They’re places to belong.

Photo Credit: Nick Garcia

Photo Credit: Nick Garcia