Omar owns a small fleet of cars in Tegucigalpa, works as a driver, and manages other drivers. His small business survives despite the constant threat posed by gangs and organized crime networks that conduct their illegal business in Honduras, a country mired in violence. “I have to pay extortion,” he says. “Otherwise, I can’t work.” He’s referring to the threatening calls he receives regularly demanding payments. This robust man supports the conservative National Party and makes no secret of his sympathy for former president Juan Orlando Hernández, who was released by a pardon from Donald Trump after being sentenced to 45 years in a U.S. prison for his ties to drug trafficking. Omar’s reason for supporting the politician is simple: he says he felt safer under Hernández’s government. His support is a reflection of how divided the country is after the release of a president also accused of corruption on a massive scale.

“Now I only have to pay one criminal group,” Omar says resignedly. “Before, up to three groups would call me, but that decreased with Juan Orlando’s iron fist. They would kidnap fellow drivers and demand ransoms for their release. They killed several. Once, they called us demanding 100,000 lempiras (about $4,000) to release one of our colleagues. They threatened to cut off a finger or his hand. We scraped together 25,000 lempiras and paid,” he recalls. He says that with the current government of Xiomara Castro, the feeling of fear has returned, so, for him, Hernández’s administration wasn’t bad. He doesn’t forgive him, however, for the corruption cases and especially for having remained in power in violation of the Constitution, which categorically prohibits reelection. He maintains, however, that Hernández was the victim of political persecution.

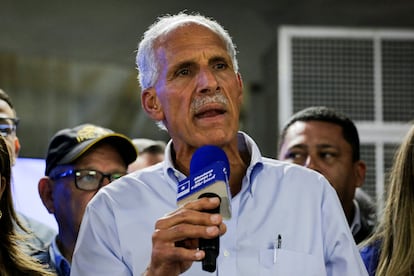

Juan Orlando Hernández in Tegucigalpa, in April 2022. Jorge Cabrera (Getty Images)

Juan Orlando Hernández in Tegucigalpa, in April 2022. Jorge Cabrera (Getty Images)

This is how the landscape in Honduras has changed in the four years since the politician’s arrest. People voted overwhelmingly against the National Party in the 2022 elections, a clear demonstration of their weariness with corruption and what was known locally as the “narco-state,” because Hernández’s critics maintain that part of his government’s power rested on pacts with drug traffickers. Meanwhile, public discontent grew due to the corruption scandals that plagued his presidency. One of the most notorious cases was the embezzlement of over $200 million from the social security institute. Journalistic investigations revealed that some of that money was used to finance the National Party’s election campaign.

“The pardon doesn’t erase the accusations of drug trafficking, using the state for organized crime, and arms purchases. The pardon doesn’t erase what he politically represented in terms of state intervention, privatization, repression, and militarization,” explains Lucía Vijil of the Center for Studies for Democracy (Cespad), a progressive organization that monitors power in Honduras. “In the historical memory of this country, Hernández represents the negative aspects, the interests of business and organized crime.”

In the political spectrum, the division is more pronounced. The so-called hardline vote of the National Party (an organization that throughout the country’s political history has shared power with the Liberal Party) supports Hernández, to such an extent that his wife, Ana García, participated in the primaries of that political organization and obtained 20% of the party’s support.

In Honduras, politics has always been controlled by families, as shown by the current leftist government of Xiomara Castro: her husband, former president Manuel Zelaya, is a presidential advisor; her son Héctor is a private secretary; another son, Jose Manuel, is Minister of Defense, and her brother-in-law, Carlos Zelaya, is Secretary of Congress.

Nasry Asfura on November 30.Leonel Estrada (REUTERS)

Nasry Asfura on November 30.Leonel Estrada (REUTERS)

The nationalist candidate in the November 30 election, Nasry Asfura, justified the pardon of Hernández as a nod to his core supporters. “For the family, the pardon puts their sorrows behind them and allows them to regain the peace and happiness they deserve,” the politician said.

Zelaya, for his part, criticized Trump’s interference in the election and called it an “electoral coup” against the candidate of the ruling LIBRE party, Rixi Moncada. “They resort to interference because they can’t win fairly. The maneuver is crude: a blatant, threatening, unjust, and infamous foreign intervention to twist the popular will,” Zelaya wrote on social media. “They make the same mistake as always: underestimating the Honduran people and our capacity to fight. Mr. Donald Trump, you don’t intimidate us. We have withstood coups, monumental fraud, political assassinations, and persecution. If we survived the narco-dictatorship, do you think one of your tweets is going to bend us to your will?” the former president said, referring to the 2009 coup that ousted him from office.

Zelaya’s party, LIBRE, emerged from the popular movements that gained momentum after the coup, including the National Front of Popular Resistance (FNRP). Its humiliating defeat in Sunday’s election (it only garnered 19% of the vote) is seen as a punishment from the electorate that supported it in 2022 in the hope of change. “It failed to thoroughly confront the power structures that dominate the country, compounded by its disconnect from grassroots organizing and the inefficiency of some state officials, who abandoned their social commitment to prioritize personal interests,” explains the Civic Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras (COPIHN), the organization to which activist Berta Cáceres, murdered in 2016 during Hernández’s administration, belonged.

Among those convicted for that crime are the three hitmen who shot the environmentalist, three former military personnel, and two workers linked to the company Desarrollos Energéticos S.A. (Desa), which would build the hydroelectric dam that Cáceres opposed.

“Hondurans have no historical memory,” criticizes analyst Vijil. “It seems there’s no understanding of what the web of corruption and drug trafficking entailed in all state institutions and the consequences it has had,” she adds. “But Hondurans have a lot of faith in the United States and see it as a benchmark in terms of the kind of country we aspire to be.”

What is clear is that Hernández remains an influential figure in Honduras, as evidenced by opinions like that of small business owner Omar, who is willing to forgive him despite the accusations and court convictions against him. “He has leadership within the ranks of the National Party and could be an opposition candidate because he managed to shape, reshape, and redesign the state to serve his interests,” Vijil notes. “What is happening in Honduras is a disappointment in terms of justice, but we must wait to see what the true reaction of the people will be if Hernández sets foot in the country.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition