In Doral, a suburb just west of Miami where nearly 40 percent of residents trace their roots to Venezuela, a bust of Simón Bolívar sits mostly unnoticed beside a strip mall parking lot, one block from the popular café El Arepazo. Bolívar, the 19th-century independence hero, has long been claimed by Venezuela’s socialist regime as the ideological father of its “Bolivarian Revolution.” But in Doral—often dubbed “Doralzuela”—exiles have tried to reclaim him as their own.

The city is part of a much larger diaspora: more than 545,000 Venezuelan-born residents now live in the United States, according to U.S. Census estimates. About one-fifth of them are concentrated in Florida, but Doral has become more than a hub—it’s a kind of exile capital, where politics spill over into everyday life.

Inside El Arepazo, one of the city’s best-known gathering spots, the energy has shifted. The tables where exiles once argued over elections and strategies for change now feel subdued. Near the entrance hangs a poster of Venezuelan opposition leader María Corina Machado, who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in November. No one points to it. No one brings her up. Conversations have turned elsewhere.

Staff glance up when unfamiliar faces enter. “People just don’t talk anymore,” one employee told Newsweek. “They look around before answering even small questions.” Some regulars have stopped coming altogether—and when they do, it’s just to watch the Real Madrid matches. Many fear that speaking openly about Venezuela could endanger relatives or jeopardize their immigration cases, especially after President Trump’s rollbacks of Temporary Protected Status, or TPS —a program that lets eligible migrants live and work legally in the U.S.—and humanitarian parole.

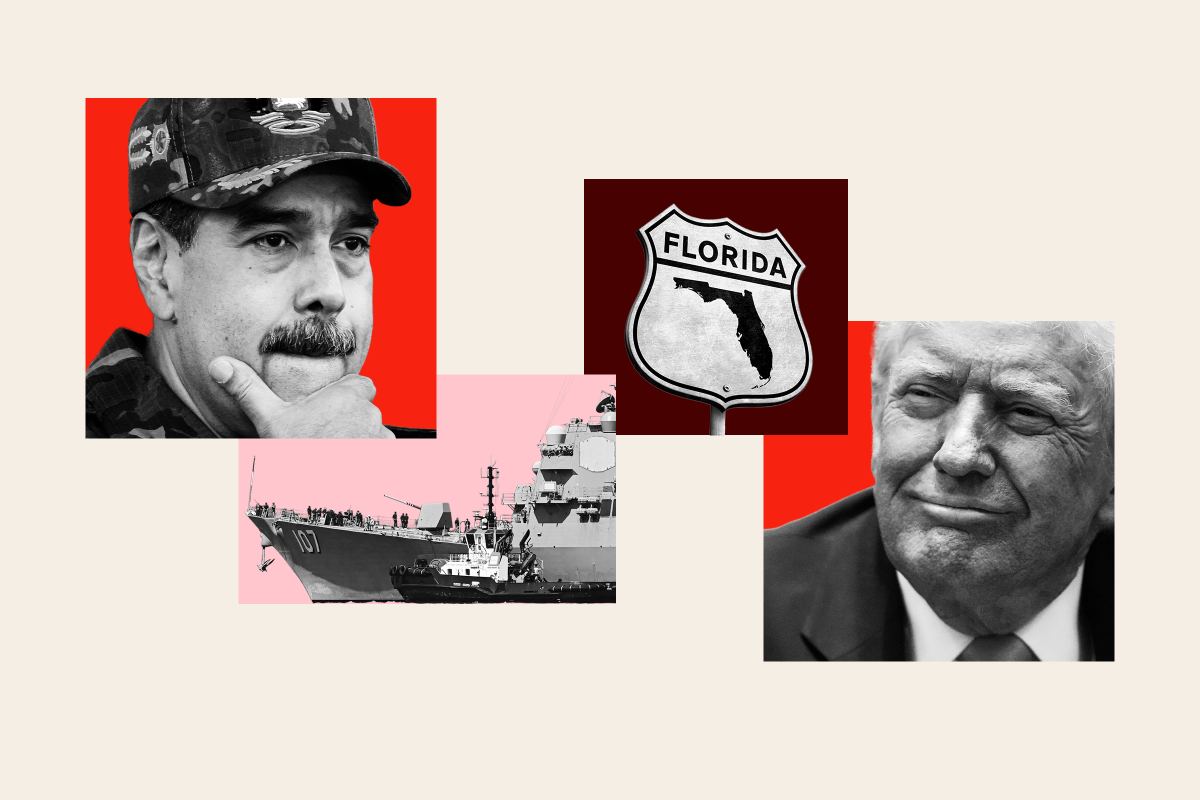

That silence has deepened over the past month, as Trump intensified military operations in the Caribbean. On Tuesday, he announced that land strikes on Venezuelan targets would begin “very soon,” marking the sharpest escalation yet in a campaign that has already included weeks of covert naval maneuvers and more than 20 boat strikes—operations the White House says are targeting drug routes protected by Nicolás Maduro’s regime.

Most Americans don’t seem convinced about this growing drumbeat of war. National polls show broad opposition to military intervention in Venezuela. A CBS News/YouGov poll released November 23 found that most Americans disapprove of military strikes in Venezuela, citing doubts over whether they would reduce drug trafficking or improve U.S. security.

But in Doral, the sentiment is starkly different. Many see the escalation not just as justified—but long overdue.

“We’ve tried everything,” said one man outside El Arepazo, who declined to give his name. “We voted. We marched. We begged. Nothing changed.” For many Venezuelan exiles in the city, Trump’s threat isn’t seen as provocation. It’s viewed as the last remaining option.

Eduardo Gamarra, a political science professor at Florida International University who has tracked Latino voting trends for over three decades, said the divide reflects the diaspora’s lived experience. “There’s a segment that still believes Trump and Rubio were serious when they said the goal was to topple Maduro,” Gamarra told Newsweek.

Backing Trump, Despite the Past

Even as legal protections unravel and fear grows across immigrant neighborhoods, many Venezuelans in South Florida still view Trump as their best—and perhaps only—hope to oust Maduro. That contradiction doesn’t erode their support. It complicates it.

Trump’s threat of military action has rekindled support among those who believe regime change is long overdue. “Even if he hurt us with TPS, if he gets rid of Maduro, we’ll forgive him,” said Felipe, a longtime Doral resident and former Trump campaign volunteer now facing possible deportation. He said the sentiment is common in a city where Trump flags once bloomed across lawns and pro-Trump caravans jammed streets during the 2024 election.

“Trump’s message of anti-socialism, especially when paired with the idea of using force against Maduro, resonated with the older Venezuelan electorate in a way no other candidate could,” Gamarra said. “He became the symbolic figure of the fight against Chavismo [the socialist political ideology associated with Maduro’s predecessor, Hugo Chavez].”

Meanwhile, repression inside Venezuela has only intensified. According to the human rights group Foro Penal, more than 800 people remain imprisoned for political reasons, and over 18,000 have been detained arbitrarily since 2014. Even private messages criticizing the government have led to lengthy prison sentences under Venezuela’s sweeping anti-hate laws.

For many exiles watching from afar, that escalating crackdown only deepens the urgency. Even voters burned by past promises—Trump’s failed embrace of opposition leader Juan Guaidó, the rollback of TPS, or stalled sanctions—cling to a belief that this time will be different. “There’s disappointment, yes,” said one longtime Doral resident. “But there’s also trust. We think he’s the only one who has the guts to do something.”

That loyalty runs deep. In 2024, Trump won more than 60 percent of the vote in Doral, helping flip Miami-Dade County red for the first time since 1988. His promises to “crush socialism” and “liberate Venezuela” electrified Venezuelan voters, who mobilized with rallies, caravans and lawn signs in ways that set them apart from other conservative Latino blocs in Florida.

And by November, according to FIU’s latest survey, half of Trump’s Venezuelan supporters in Florida still stand by their vote, bolstered by his recent stance on Venezuela.

‘Not Like Us’

The political divide among the exiles of Doral runs deep, rooted in the timelines of departure and the reasons people left in the first place.

Two waves of Venezuelan migration have shaped this community. The first began in the early 2000s as Chávez consolidated power. Many who fled during that period were part of the professional class—lawyers, business owners, engineers—with the resources and documentation to resettle through legal channels. They became homeowners, built businesses and aligned quickly with South Florida’s Republican establishment. Their opposition to Chavismo was unwavering—shaped by the sense of what they lost and what they rebuilt.

A second, larger wave followed in the wake of Venezuela’s economic collapse under the Maduro regime. This migration was born not from politics but desperation. Venezuela’s GDP has contracted by more than 80 percent since Maduro took office in 2013, according to the International Monetary Fund. As food shortages, hyperinflation and state violence spiraled, families fled in droves. Many arrived without papers or long-term visas, relying instead on temporary measures like TPS or humanitarian parole. They were younger, often working class, and took up the jobs that now sustain much of South Florida’s service economy—construction, delivery, restaurant work.

The gap between the two groups remains visible, and at times, tense. In interviews and focus groups conducted by Gamarra’s team, earlier arrivals often draw sharp distinctions. “They’re not like us,” some said—describing the newcomers as less educated or, in some cases, suggesting they had once supported the very regime they later escaped.

According to FIU data, roughly 70 percent of Venezuelan Americans in Doral arrived before 2014—most during the early Chávez years—and it is this group that now forms the backbone of Trump’s support. Many no longer rely on immigration protections like TPS or humanitarian parole. In fact, some openly support ending those programs, arguing they’ve been misused or abused by newer arrivals.

But for those who came more recently, the rollback of those protections has been nothing short of devastating. Trump’s post-election decision to cancel TPS and parole for Venezuelan migrants stripped legal safeguards for hundreds of thousands. At the time, more than 320,000 Venezuelans across the U.S.—many of them in Florida—were living under those temporary protections, according to Department of Homeland Security estimates.

Among these newer arrivals, the mood is different. Many are more cautious—worried both about family back home and the impact of losing legal protections—and their support for Trump is softer than that of earlier exiles.

‘The shot clock is running’

Not everyone in Doral is convinced that regime change is imminent. For all the support Trump commands, doubts linger. “We’ve heard this story before. What if this is just another show? What if we’re left with nothing—again?” said Victor, a 34-year-old Uber driver and asylum seeker.

Military analysts say time is running short. “There’s no strategic rationale for sending the [USS Gerald R.] Ford to the region unless it’s intended for use,” said Mark Cancian, a senior adviser at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, in an interview with Newsweek. “The shot clock is now running. They’ll either need to act or redeploy it, and pulling back would amount to backing off.”

Trump recently designated the Cartel of the Suns—a shadowy network of military-linked traffickers—as a foreign terrorist organization, paving the way for expanded U.S. military authority in the region. The move, while largely symbolic, lays legal groundwork for targeted strikes beyond traditional anti-narcotics operations.

Such uncertainty is familiar to many in Doral who feel bruised by memories of broken promises. They recall the fanfare around Guaidó’s rise, his White House visits, the bipartisan ovation at the State of the Union. Then came sanctions, more speeches, a new election, and eventually, silence. “Venezuelans haven’t forgotten what happened last time,” Gamarra said. “They were promised protection, support, regime change. Instead, they saw deals, delays, and now—deportations.”

Florida GOP Representative María Elvira Salazar, one of Venezuela’s most vocal critics in Congress, framed the administration’s latest moves as a necessary correction. “Thanks to Trump, who has the internal fortitude to do what’s right,” she told Newsweek. Still, she acknowledged the weight of the moment. “We are in a battle for the Western Hemisphere,” said Salazar, a Cuban-American and former news anchor. “And the people of Venezuela are watching.”

In Doral, many are more than watching. They are waiting for what comes next. An armada of U.S. warships sit just off their homeland’s coast. And in the city that many Venezuelans now call home, some believe those ships could finally bring the change they’ve long hoped for. But they also know it could come with a cost.

“My family is still there. I can’t say anything. Not even in the U.S.,” said a woman inside El Arepazo, declining to give her name.

Fear continues to shape daily life for those with relatives in Caracas, as well as for anyone wary of drawing attention to their immigration status. Still, many support the military buildup. While much of the U.S. views the warships as a provocation—or the start of another overseas quagmire—in this city shaped by exile, they’re seen differently: the only option left.