By Sarah M. Boye from the Fall 2025 Edition of Reflections Magazine

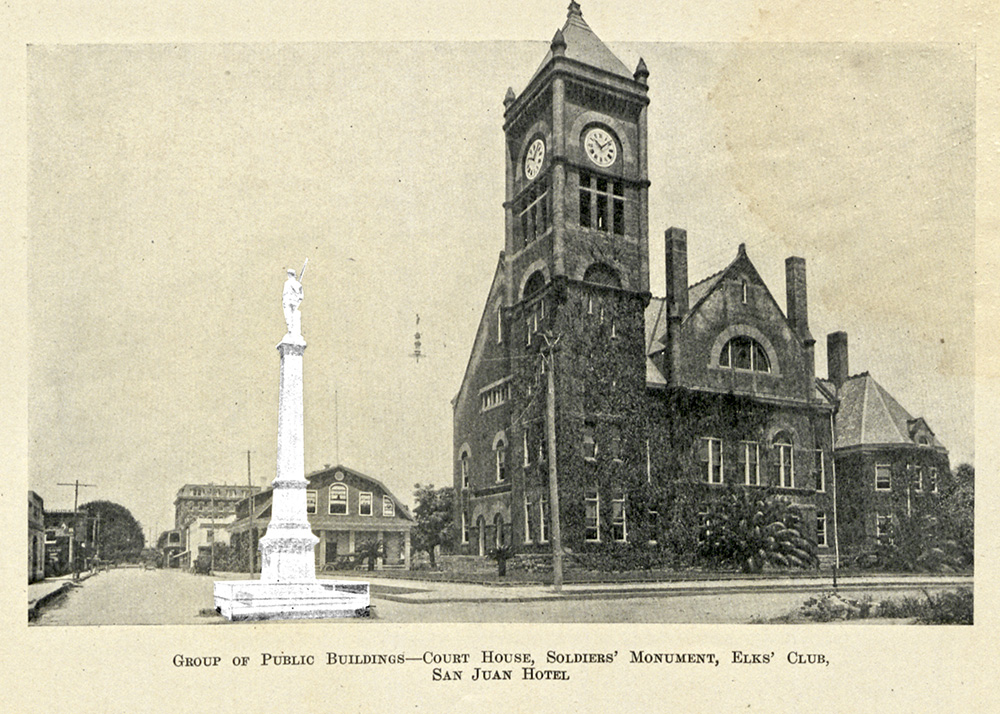

In 1917, a Confederate monument placed in downtown Orlando in 1911 was moved to Lake Eola Park, where it stood for decades. In 2017, it would be moved again to Greenwood Cemetery. It’s a good bet many Orlandoans don’t realize that the statue of a soldier on a tall pedestal began on Central Boulevard, near the Orange County Courthouse, much less that its early move to Lake Eola was linked to a Syrian immigrant to the city named Naif Forage.

On Sept. 16, 1914, Forage accidentally crashed his car into the monument in the heart of downtown. Newspapers treated the incident as little more than a joke, and it’s been all but forgotten. But these decades-old reports open a window into a hidden chapter of Central Florida’s past.

Opportunity and adversity

What seemed like a mundane accident reveals the overlooked story of a Syrian immigrant family and their place in Orlando’s history. Through Naif Forage’s life, we glimpse the challenges of racial identity, entrepreneurship, and belonging in a city still defining itself. Growing concerns about the monument’s location were raised after the crash, and it was deemed a traffic hazard. That a Syrian immigrant accidentally triggered the relocation of a symbol of white Southern memory seems deeply ironic, especially in a city whose immigrant history has long focused on Anglo-European narratives.

Born on Jan. 20, 1887, in Al-Nebk, Syria, a city with deep Catholic roots, Naif Forage was part of a generation of Syrian Christian immigrants who left the Ottoman Empire. As its Arab provinces strained under Turkish rule, many of them, like Forage, sought economic opportunity and freedom from social constraints. He came to the United States in 1905 at the age of 18 and arrived in Orlando as the city was growing out of its frontier roots. His brothers, Abraham, Assad, and Abdellah, soon followed, settling in Orlando and Tampa. By 1911, Naif had become a naturalized U.S. citizen. He married Leila Page, a South Carolina-born widow who was ten years his senior and an educated woman, active in causes such as the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. Their marriage reflected how early Syrian immigrants sometimes built ties across cultural lines, helping them assimilate into American society.

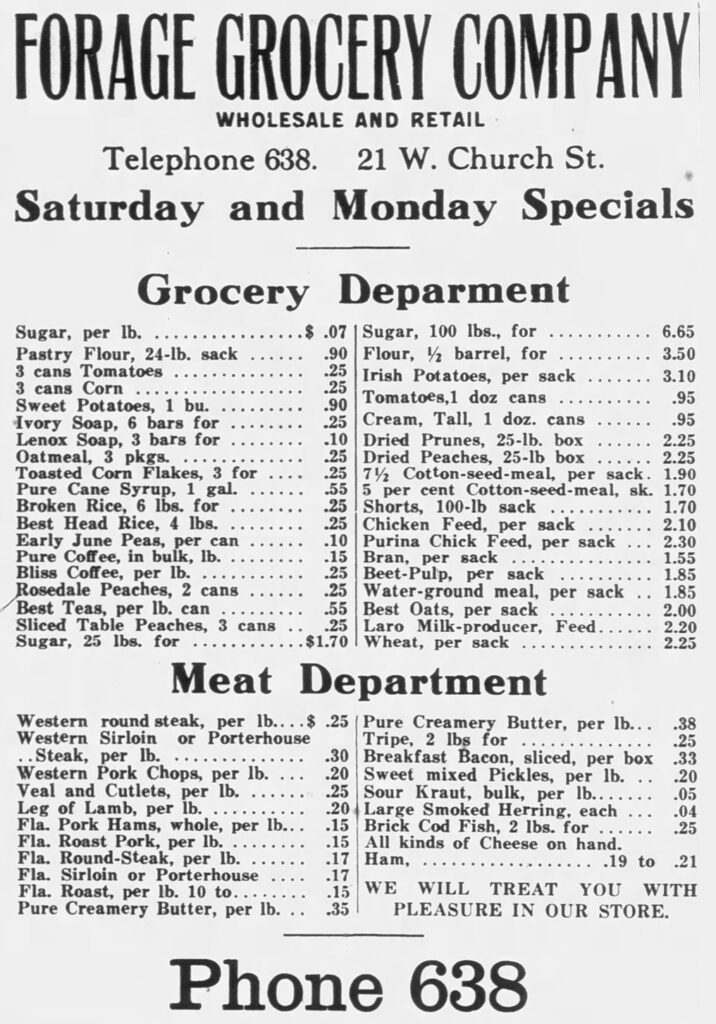

Forage and his family’s life in Orlando quickly took shape through commerce. By 1909, he was running a fruit and grocery store at 132 S. Orange Ave. His brothers Assad and Abdellah worked with him and lived nearby. In 1911, he told the Orlando Evening Star that “business sure is fine in Orlando.” He purchased an orange grove and grew his ventures, moving his store to 21 W. Church St. in 1912. He began a successful advertising campaign in the Orlando Morning Sentinel. In November 1913, he leased the former Laubach building on West Church and held the grand opening of a new, expanded store.

But everything wasn’t a bed of roses for the Syrian family. Just weeks before touting his new store, Forage had been charged in a high-profile assault case. In August 1913, an altercation took place near the Atlantic Coast Line station, close to Forage’s business. A police officer accused him and his brother Assad of threatening him with revolvers. Forage denied the charge, describing the incident as a confrontation initiated by the officer, who allegedly told him, “I am going to run you bad people out of this town.” Forage insisted that neither he nor his brother ever brandished a weapon. The trial ended in a swift acquittal, with the jury deliberating only briefly. The Forage brothers were proud of the defense offered by several prominent local businesspeople, including a future Orlando mayor, James LeRoy Giles.

On May 19, 1914, Naif Forage was again brought to court, this time accused of using profane language. The case highlighted cultural tensions, as the judge struggled with a courtroom full of Syrian and Greek witnesses. The charge was dismissed when the language Forage had used was found to not have been profane. Then, on Sept. 16, 1914, Naif Forage’s name again returned to the newspapers when his car collided with the Confederate monument.

The article about the crash was hardly serious, however. The writer noted that Forage’s car had “thoroughly disliked the monument” and “ingloriously failed” to move it. One line quipped that he had attempted to “drive on both sides of the monument at the same time.” Although the tone was lighthearted, the symbolism of an immigrant crashing into a monument to white Southern memory may carry a deeper resonance today.

Tragedy and Triumph

Besides commercial success and legal tangles, the years between 1911 and 1914 also brought tragedy for the Forage family. In 1911, Assad married a 17-year-old Syrian immigrant from Al-Nebk named Katherine Rizook. Weeks after the birth of their son David in 1913, she died from puerperal septicemia, also known as childbed fever. Baby David died of pneumonia four months later. Both were buried in St. Mary’s Catholic Cemetery off what’s now Edgewater Drive. Assad appeared in court during this time, charged with “loud talking” just days before David’s death. Although the charge was dismissed, it may be seen as a reflection of how immigrants were often targeted or misunderstood by authorities in a small Southern city such as Orlando.

Trouble, as well as success, continued in Naif Forage’s life. On Saturday, March 18, 1916, he was nearly killed during a violent encounter at his grocery store. P. H. Rogers, the former owner of the Star Meat Market on Church Street, came into the store about 8 p.m. and asked Forage to come to the back of the store, according to the Morning Sentinel’s front page report on March 19. Forage tried to calm Rogers down, but Rogers struck him in the chest and pulled out a .32 caliber revolver, which he fired wildly. The bullet narrowly missed Forage but hit his clerk, A. K. Demetrie, over the heart. The newspaper report declared that a pocket comb in Demetrie’s vest had deflected the shot, saving his life. Forage and Demetrie subdued Rogers, who was arrested. The Sentinel writer theorized that a dispute about ownership of a meat-cutting block might have inspired the fracas.

Business leader and patriot

That same year, 1916, Forage joined the Orlando Board of Trade. By this time, he was recognized as a civic-minded businessman and continued to build his reputation. The following year, during an influenza pandemic, he launched a promotion at his store, pledging 2 percent of a week’s gross receipts to help build Orange General Hospital. The resulting $75 donation suggests his store brought in the modern-day equivalent of over $90,000 that week.

While making meaningful contributions to Orlando, he also embraced his patriotic duty to his new country. He registered for the World War I draft and purchased over $2,000 in Liberty Bonds in 1918, stating, “I am a Syrian and I thank God I am an American citizen!” That same year, he gave a speech to fellow Syrian American servicemen, expressing pride in their contributions and reaffirming their American identity. While he enlisted in the Quartermaster Corps and often spoke with pride about joining up, he was never called to serve.

Yet, for all Naif Forage’s patriotism, he and his brothers lived in a nation where racial identity was both a social and legal construct. Syrian immigrants were not always considered white. This ambiguity came to a head in the 1915 Supreme Court case Dow v. United States, where a Syrian immigrant had been denied citizenship for not being white. The court ultimately ruled Syrians could be classified as white under U.S. naturalization law. Naif Forage had been naturalized before the ruling, but in 1918, both his brothers Assad and Abdellah faced complications. Abdellah was listed as a nondeclared alien and classified as “Oriental.” Assad’s naturalization paperwork was confiscated by a government official who claimed it was invalid. Though legally white, they were still viewed with suspicion.

Despite such challenges, Naif Forage seemed to thrive in Orlando. He opened a five-and-ten cent store, expanded his grocery business, shipped cattle, dealt in real estate, and owned groves and farms. The brothers operated as Forage Bros., with locations across Florida. Over time, they moved in search of new opportunities to cities including Gainesville, Arcadia, and finally Winter Haven. Their story reflects the ambition of early immigrants. Hardship returned, however, and after a few failed ventures, the brothers were forced to declare bankruptcy in 1921.

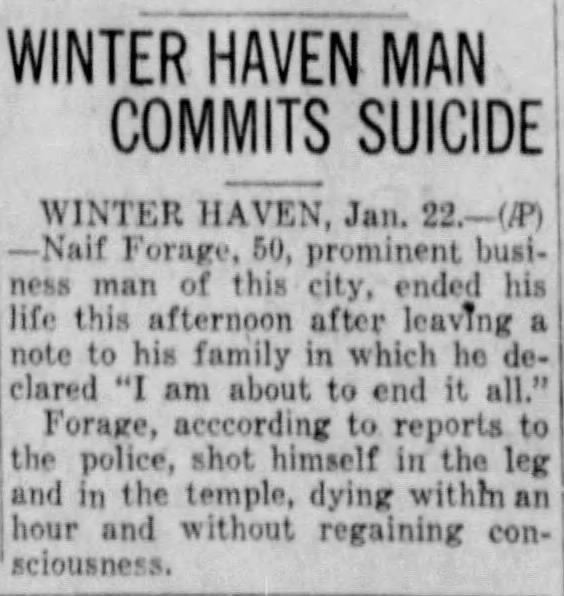

Six years later, following continued setbacks, in January 1927, Naif Forage died in what was ruled a suicide in Winter Haven. He left a note to his family, which read, “I am about to end it all,” before shooting himself first in the leg and then in the temple. Because of the nature of his death, he was denied burial in St. Mary’s Catholic Cemetery, where his sister-in-law and nephew were interred. Instead, he was buried in an unmarked grave in Greenwood Cemetery, in the city he still considered home. That November, Assad also died by apparent suicide and was buried beside his brother. Two months later, Abdellah was institutionalized at the Florida State Hospital for the Insane and died in April 1928. His intake records note that he spoke little English, complained of being beaten by police in Winter Haven, and was prone to speaking in his “foreign language,” which “annoyed” other patients. He too was buried near his brothers. Abraham, the only surviving Forage brother, remained in Tampa until his death in 1957.

The Forage family story is one of ambition, resilience, and tragedy. Perhaps it reflects the promise and the cost of the American Dream. Naif Forage’s success as a business and civic leader was real, but so were the social and legal barriers he and his family faced. Their story reveals the personal toll of navigating a society where belonging was conditional. Naif Forage’s car crash into the Confederate monument was quickly forgotten by the press, but it opens up deeper questions about who gets remembered. Early Syrian immigrants helped build Orlando economically and culturally, yet their absence from mainstream history reflects a tendency to center some and overlook others. Today, the Confederate monument has been removed from its public pedestal at Lake Eola Park and relocated to Greenwood Cemetery, not far from the unmarked graves of Naif, Assad, and Abdellah Forage. Their proximity invites us to reconsider how we remember Orlando’s past. The Forage family’s story complicates our understanding of race, memory, and identity in early 20th-century Central Florida and urges us to honor the legacies that history too often buries.