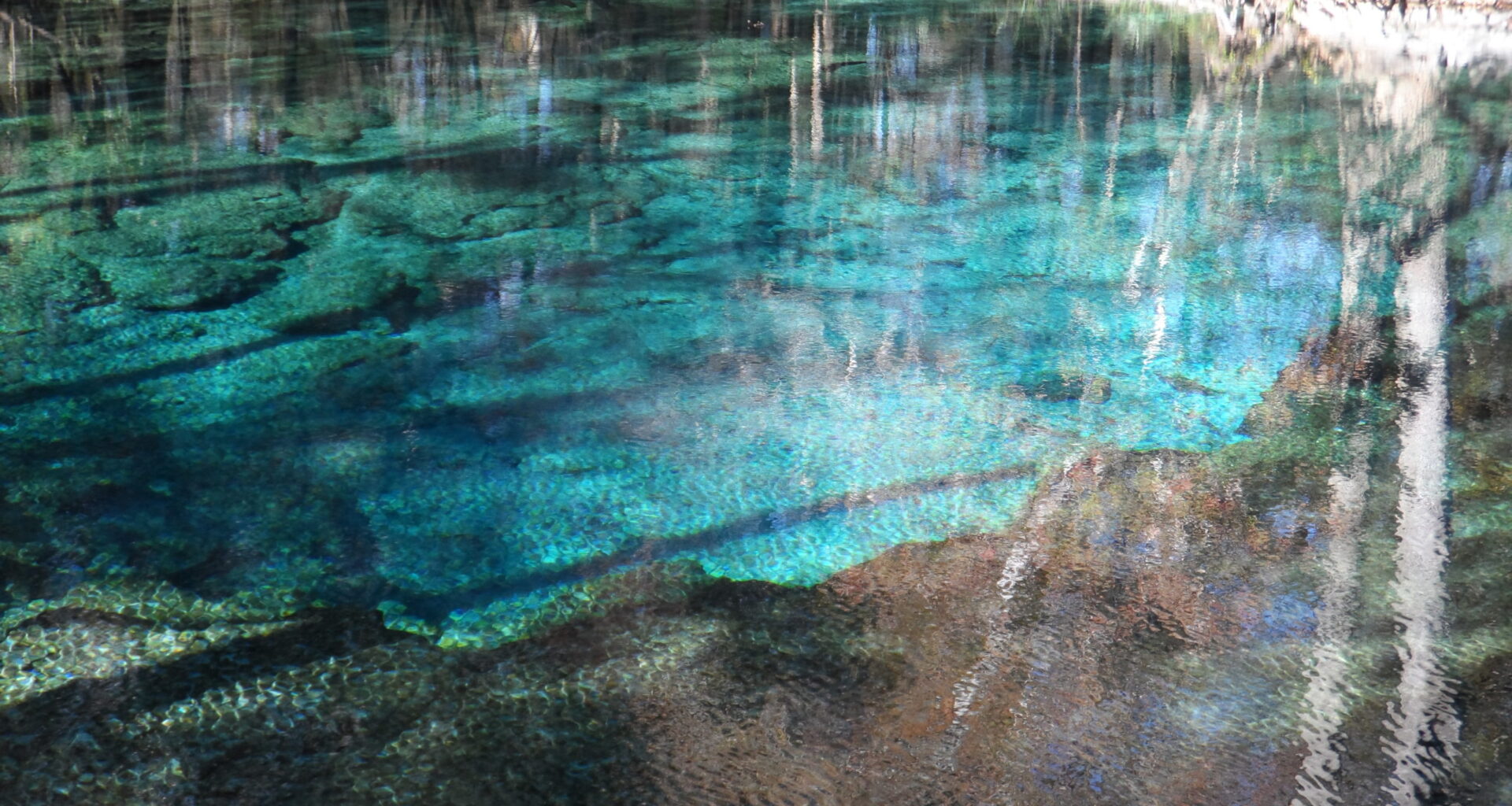

Devil Spring In Ginnie Springs. By Seán Kinane / WMNF News (Nov. 2012).

by Craig Pittman, Florida Phoenix

December 11, 2025

This is the time of year many of us go searching for something. We look for good deals on Black Friday and beyond. We hunt for a good place to hide the gifts we’ve acquired for our family and friends. We seek some semblance of holiday cheer amid the tumult of the day.

That’s why I’m happy to tell you that something that’s long been hidden has reappeared recently: the Lost Springs of the Ocklawaha.

No need to search for them. They’re right out in plain view — for a little while.

Most Floridians don’t even know they exist. Yet there are 20 or so, with names like “Cannon Spring,“ “Bright Angel Spring,” and “Tobacco Patch Spring.”

They’re not on any road maps. Unlike a lot of Florida’s springs, they’re not part of any state or national park. They might be considered part of a national forest.

You can’t see the lost springs unless the Florida Department of Environmental Protection conducts a procedure known as a “drawdown.” That’s when the lost springs re-emerge, and you can not only see them, but you can also visit and even swim in them.

Karen Chadwick via Florida Wildlife Federation

There’s a drawdown going on right now, so charter captain Karen Chadwick took her boat out to renew her acquaintance with the lost springs. When she sees them flowing, she told me, “It’s the most beautiful place in the world.”

Margaret Ross Tolbert via screen grab

“It’s just incredible,” agreed her friend Margaret Ross Tolbert, a Gainesville artist whose paintings often feature Florida springs. “I’m always amazed at how they can bounce back.”

Just last week, Gov. Ron DeSantis was bragging at a Tampa press conference about Florida’s springs, but his words sounded hollow.

“We have the best springs of anywhere in the country,” he said.

If DeSantis really loved our springs the way he pretends to, he’d help the lost springs stay found. But so far, he hasn’t done it.

When the drawdown ends in March, those springs will get lost all over again. If that happens, it will be his fault.

What we’ve lost

In 1971, Elizabeth Abbott of the University of Florida’s Department of Geology wrote a report on these springs.

Here’s how the report described Blue Spring No. 1: “The spring was perfect for those wanting to get away from it all. It was privately owned for many years but always open for public use — swimming and fishing, as well as picnicking and camping.”

The spring’s natural beauty was exceeded only by its natural bounty, Abbott wrote.

“The most discriminating of seasoned fishermen marveled at the quality of fish [in] Blue Springs — not to mention the quantity,” she wrote. “Freshwater mullet and catfish swam like giant denizens convoyed by nervous bream, but the large bass was the most sought-after catch.”

Cannon Springs right now, via Margaret Tolbert

Further along, at Cannon Springs, she wrote, “The forest here is perhaps the most beautiful of all the river. It is a low hammock type with a mixture of palms and hardwoods. The cry of the limpkin is a noisy and interesting distraction.”

Orange Spring, she reported, is a sulfur spring, “with a walled-in circular pool about 75 feet across. The boil is about 18 feet deep. … The sulfur is said to be organic in origin.”

She credited the river’s many springs with swelling the flow of the river itself, as well as maintaining its water’s purity. It’s not mentioned in the report, but those springs were probably popular with manatees, which once used the Ocklawaha to migrate to the St. Johns River. I’m sure the early settlers and Native Americans who found the springs regarded them as pure magic.

Thus, to sum up, the springs were popular for recreation, provided habitat for a wide variety of wildlife, and helped maintain the river’s flow and purity.

Steven Noll via UF

“They were pretty well used by the local people in that area,” historian Steve Noll told me. “They were full of fish, too.”

No wonder that when they’re uncovered, people flock to the river to see them anew. Too bad they’re not available but for a few months every few years, due to one of the stupidest public works projects ever attempted.

Digging our grave

The Ocklawaha was once a river of dreams. But then came the Army Corps of Engineers to turn it into a nightmare.

The reason you can’t see these 20 or so springs year-round is because they’re inundated by the Rodman Reservoir. That 17,000-acre artificial body of water was created in 1968 when the Corps built the controversial Kirkpatrick Dam.

The dam is a 7,200-foot-long structure that impounded 16 miles of the 80-mile river, drowning a chunk of the Ocala National Forest.

It was built as part of the idiotic Cross-Florida Barge Canal. The canal was an 19th century idea built in the 20th, an attempt to slice a shortcut across the Florida peninsula for ships — even though, by then, most freight was being carried by trains and trucks.

Opponents could see what a disaster this canal would be. It wasn’t just that by damming the Ocklawaha, the corps would end a popular waterway connection between Silver Springs and the St. Johns River.

The excavation would also cut into the aquifer that supplies most of Florida’s fresh water, allowing salt water to intrude. The Corps was digging Florida’s grave.

David Tegeder. (Photo by Matt Stamey/Santa Fe College)

**Subjects Have Releases***

The fight to stop it was funded by John Couse, a well-to-do air conditioning contractor who owned a home near Cannon Springs, said historian David Tegeder, who with Noll wrote “Ditch of Dreams: The Cross Florida Barge Canal and the Future of Florida.”

Crouse became involved after seeing the Army mowing down trees using a tank-like machine called the Crawler-Crusher, which did exactly what its name said. Seeing the damage done around the spring gave him a reason to fight.

The canal’s opponents won a temporary injunction. Their efforts got the attention of President Richard Nixon, who canceled construction of the canal.

Now the former canal route is a 110-mile linear greenway for hikers, bikers, and horseback riders named for the canal’s most vocal opponent, scientist-turned-activist Marjorie Harris Carr.

Unfortunately, every effort Carr and others after her have made to rip out the dam has been thwarted.

A woman splashes into a revived Cannon Springs during filming of the “Lost Springs” documentary, via Margaret Tolbert Dead Lakes and dammed river

Some people want to keep the reservoir intact. They fear what will happen to the fishing if the dam goes away. I point those folks to the story of the Dead Lakes dam in the Panhandle.

After a three-year drought kept the Dead Lakes too low for fishing, the Legislature approved putting a dam on the Chipola River. Built in 1960, the 18-foot-tall dam was supposed to boost fishing by maintaining high water levels.

When the dam was new, fish corralled in the reservoir became easier to catch. Over time, though, the reservoir clogged with silt and weeds. Soon the remaining fish were so small they were hardly worth catching.

In 1987, the state removed the dam, allowing the natural lake level to return. Fisheries biologists studied the Dead Lakes for years afterward and found they were now healthier. There were more and bigger fish. And there were twice as many kinds, too.

Oklawaha Valley Railway Company map c. 1900 via State Library and Archives of Florida.

That’s why I think the anglers shouldn’t resist restoring the Ocklawaha. They should embrace it — assuming it ever happens.

The most recent effort to remove the Rodman dam happened last year. The Legislature voted to spend $500,000 for an updated study of ripping out the decrepit old dam and freeing the Ocklawaha. The last such study was nearly 30 years ago.

The new study was supposed to be done by the University of Florida Water Institute — not exactly a fly-by-night outfit. It was intended to provide legislators with up-to-date information so they could make an informed decision about the dam.

To everyone’s surprise, DeSantis vetoed the money. He became the first governor from either party since the ’70s to actively oppose restoration of the Ocklawaha. He offered no explanation, either

The springs and the cypress trees that were drowned by the reservoir stayed covered.

Until two months ago.

The drawdown

Every four or five years, the DEP has to draw down the reservoir, lowering its water level. They do this to clear out the aquatic plants that clog the system.

Nina Bhattacharyya via Florida Defenders

The current drawdown began in October, according to Nina Bhattacharyya, now executive director of Carr’s organization, Florida Defenders of the Environment.

“We are encouraging people to get out there and get a glimpse of what a restored river would look like,” Bhattacharyya told me.

The alteration in the waterway is dramatic. With the water lowered, you can see all the cypress stumps from the national forest. As for the springs, they’ve been jolted back to life.

“Any time one of these happens, people rush out to see the lost springs,” Bhattacharyya said.

One of the people who rushed out was Ryan Worthington, whose Instagram account is called “The Florida Excursionist” and who co-hosts a podcast called “The Florida Madcaps.”

Ryan Worthington via Instagram

“I went out to Cannon and to Tobacco Patch,” he said. “A lot of the others are small in size and back in the woods so they’re hard to get to. Cannon has the best flow and there are a lot of sunfish and other aquatic life in it.”

Tolbert has been out, too. She compared one of the uncovered springs to a volcano, suddenly producing eruptions of water gushing from beneath the earth.

The last time there was a drawdown, Tolbert was moved to film a 40-minute documentary called “Lost Springs: An Artist’s Journey Into Florida’s Abandoned Springs.” It was directed by Matt Keene, who’s also done a movie called “River Be Dammed.”

“You have to keep returning because they’re so unbelievable,” Tolbert says in the documentary. “Yet there they are, something that would only seem to exist in your dreams.”

Now let me tell you about something I dream about.

Finding the courage

In my dream, the drawdown never ends. The springs are never hidden. They remain out in the open, available for anyone who wants to swim in them or toss in a fishing line.

But what if it wasn’t a dream? The drawdown is scheduled to be over in March. But it doesn’t have to be. There’s no law that says the DEP has to return all that water to the reservoir.

What if DeSantis issued an executive order that told DEP, “Don’t put the reservoir back”? What if he decided to copy what happened with the Dead Lakes and restore the landscape?

Think about it. During his two terms, he’s repeatedly messed up this state’s natural resources. He built a polluting immigrant detention camp in the Big Cypress National Preserve. He tried to build golf courses in Jonathan Dickinson State Park. He’s refused to crack down on polluters and instead has spent millions in tax dollars to clean up their messes for them.

In fact, his DEP has repeatedly failed to comply with a state law requiring new rules for stopping the damage to our springs.

Last week, when he was talking about how wonderful our springs are, he was announcing plans to spend millions more on cleaning up pollution. What he didn’t mention is that his DEP will continue turning a blind eye to what the polluters are doing.

I tried repeatedly to get DeSantis’ spokesfolks to comment on the Rodman drawdown, or to explain why he vetoed the money for studying the aging dam. As usual, his staff wouldn’t even acknowledge my inquiries.

This is a guy who always says the buck stops somewhere else. When a reporter asked him last week why he voted to give a shady campaign contributor $83 million for a 4-acre parcel in Destin that wasn’t on anyone’s preservation list, he repeatedly tried to shift the blame. In three minutes, he blamed someone else six times.

If DeSantis is searching for a way to redeem himself and leave a better legacy than the one he has now, this is it. Here’s hoping he’s able to find the courage to save the lost springs.

Independent Journalism for All

As a nonprofit newsroom, our articles are free for everyone to access. Readers like you make that possible. Can you help sustain our watchdog reporting today?

SUPPORT

Florida Phoenix is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Florida Phoenix maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Michael Moline for questions: info@floridaphoenix.com.