If there are two truths about Charlie Crist, they are these:

Charlie Crist runs for things.

Charlie Crist always finds his wayback to St. Petersburg.

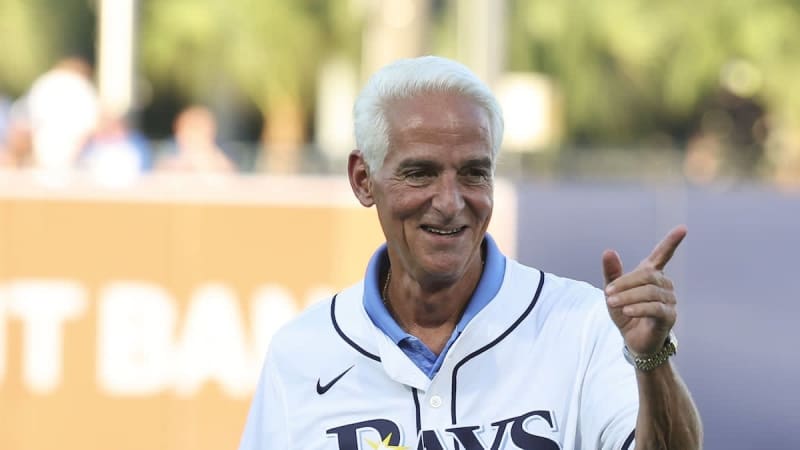

It hardly comes as a shock that Crist, a former Florida governor and U.S. representative, is mulling a run for St. Petersburg mayor. In some ways, it’s the logical conclusion to his nearly four decades in public life.

“Home is where the heart is,” he said in an interview. “I never want to leave St. Petersburg. Having the opportunity — if we decide to do so — to fight for St. Pete in an executive position, which I’ve held several, would be an incredible honor. Something that would be very important to me. And that’s why I’m giving it serious consideration.”

In his career, Crist has run for offices big and small, from state Senate to U.S. Senate. One of Florida’s legendary schmoozers, he’s held office as a Republican, an independent and a Democrat at various times. He’s earned thrilling victories, becoming Florida’s 44th governor in 2007 (as a Republican). He’s suffered humiliating losses, most notably his 2022 gubernatorial drubbing (as a Democrat)at the hands of Gov. Ron DeSantis.

No matter how high or low he’s gotten, Crist has always been welcomed by his hometown of St. Petersburg. The city where he grew up, played high school football and practiced as a lawyer has served as his power center. But as he eyes a run for mayor, the tether between St. Petersburg and one of its most prominent sons is set to be tested like never before.

Crist has a political record of four wins and three losses in the past 20 years. In each election, St. Petersburg has voted for him. Even incampaigns where he was soundly defeated, such as the 2010 U.S. Senate racewhen he ran as an independent, he still won his home county, buoyed by St. Petersburg support.

“I think it’s fair to say he’s always had a base in St. Petersburg,” said state Sen. Darryl Rouson, a Democrat. “He’s a St. Pete kid.”

When he first ran for office in 1986 at age 30, the name Charles Crist was known all over town.

Crist is the son of Charles Crist Sr., a family doctor who served for a decade on the Pinellas County School Board. Crist Sr. was a key decision-maker while Pinellas schools were being integrated in the ’70s — although he opposed the most progressive proposals to do so. His son, Charlie, worked on all of his campaigns.

In describing his first race, for a St. Petersburg-area state Senate seat, the then-St. Petersburg Times described Charlie as a “doe-eyed young lawyer” who “can borrow some name recognition from his father.” Crist finished first in a four-way primary, then lost in a September Republican runoff.

In 1992, the young lawyer took another crack atrunning for office. This time, the state Senate seat he sought spanned Tampa Bay. But he prevailed by leaning on his roots.

In the closing days of his race against Tampa native Democrat Helen Gordon Davis, Crist was the beneficiary of a Republican Party flyer that warned of Tampa’s creeping influence over St. Petersburg.

“The crew from across the Bay is at it again. But this time the pirates from Tampa aren’t looking to grab just a baseball team or a federal courthouse,” the flyer read, according to coverage at the time. “This time they’re trying to steal St. Petersburg’s political influence.”

Voters responded — particularly Pinellas voters. Crist won a greater share of his home county vote than he won overall, and he was off to Tallahassee.

This dynamic has repeated itself over the years. The last office he held, from 2017 until 2022, was a St. Pete-based congressional seat.

His policies have evolved over time. He’s been antiabortion, pro-choice, pro-gun rights, pro-gun regulation, a gay marriage supporter and a gay marriage opponent. But many voters see him as forever the boyish son of St. Petersburg.

Now 69, he wants to be the city’s mayor.

Next year’s mayoral race will appear at the bottom of voters’ primary ballots. St. Petersburg residents voted in 2022 to schedule local elections at the same time as state and federal races. That change may yield greater voter turnout than an off-year municipal race and could give an advantage to Crist with his name recognition.

Crist’s dalliance with a mayoral run is hardly a vote of confidence in incumbent Ken Welch, who was elected in 2021. Welch has not filed for reelection but has started campaigning and raising money. He opened a political committee, the Pelican Political Action Committee, after his old one, Pelican PAC, was revoked by the state for failing to file reports. The new political committee has raised $234,575 since January. Crist would also face City Council member Brandi Gabbard, who said this week that she would run for mayor, and longtime community activist Maria Scruggs.

Like Crist, Welch is the son of a popular and politically active father. The late David Welch, an accountant with an office on 16th Street South, was held in high esteem by those looking to open a business or run for office. He was the first Black man elected to the City Council.

Welch, 61, was born in St. Petersburg. Crist moved from Atlanta, where his father was in medical school, as a boy. Both Welch and Crist played football for their high schools: Welch for the Lakewood High Spartans and Crist for the St. Petersburg High Green Devils. They started their political careers as Republicans. Welch switched parties a decade before Crist did.

Bob Ulrich, mayor of St. Petersburg from 1987 to 1991, remembers Crist as a kid. Ulrich knew his mother as a teenager and taught Sunday school to one of his sisters.

Still, Ulrich isn’t sure how much Crist’s long history in St. Petersburg will matter in a revived city flush with new residents who “don’t have the background knowledge and given support of the earlier years.”

The St. Petersburg that Crist grew up in looked nothing like what it is now. Despite all the changes, Crist said he would lead the city by the name of his 25-foot open fisherman’s boat docked at his father’s house: “The Golden Rule.”

“I strive to live by that: Do unto others as you would have them do unto you. Listen to everybody. Understand that everybody matters,” he said. “Public service has obviously sort of been my calling. And if we decide to do this, to be able to do it for my hometown as mayor of this city that is so precious to me, will be an extraordinary honor.”

Times data editor Langston Taylor contributed to this report.