Rebecca Parris rushes to the bank before it closes.

The power could be shut off soon to her 960-square-foot mobile home in St. Petersburg, she fears, if she doesn’t pay Duke Energy her overdue bill. The deep red “Action Required: Bill Past Due” banner on a Dec. 16 email from the company — and the handful that came before it — makes her heart pound.

A neighbor chips in $95, and she speeds over to Bank OZK to cash the check. This month’s crisis is narrowly averted. But she’s already thinking about next month.

“I’ve worked my ass off my whole life,” said Parris, 67, still sitting in the driver’s seat of her car from her dash to the bank. “But it’s been really hard.”

Mobile homes have long been an affordable option for people with fixed or lower incomes, when a big down payment and mortgage are out of reach. But beyond the smaller purchase price lurks a hidden danger: Because of outdated manufacturing standards, mobile homes can have much higher electric bills than traditional houses.

For a series of stories on energy affordability, the Tampa Bay Times asked readers to submit information about their electric bills. Hundreds responded, and many said they paid higher bills this year than ever before. Yet even in this climate, mobile home residents stood out — some with bills ranging from $300 to $500, roughly comparable to houses twice their size.

Here’s what people across Tampa Bay are paying for electricity

Retired and on a fixed income, Parris has struggled this year to keep up.

After Hurricane Helene’s storm surge flooded her home last fall, she lost her car, her furniture, a new washer and dryer. The salt water also damaged her air conditioner, which she replaced about a month after the storm.

Then she watched this year as her Duke charges climbed:

$170.09 in May.

$258.06 in June, a payment she missed.

$314.85 in July, which ballooned to more than $500 counting what she still owed.

“It’s so so stressful and daunting,” Parris said. “I deal with financial pressures every day like this.”

Lowell Ungar, director of federal policy for the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, a national advocacy group, said that while codes for traditional houses have been constantly improving to require builders to make them more efficient, mobile home regulations haven’t budged in decades.

“In terms of their energy equipment and components, they’re not built very well,” he said, referring to the homes’ insulation, windows and water heaters, for example. “The federal code hasn’t been changed since 1994 — and it wasn’t very strong then.”

Unlike other types of housing, mobile homes are only subject to federal energy standards, not state building codes. In 2007, Congress recognized that these requirements were too weak and passed a law directing the U.S. Department of Energy to update them. That still hasn’t happened.

The agency released updated rules in 2022, but delays to their compliance date, bureaucratic back-and-forth and pressure from the manufactured home industry has led to a “long saga” of delays, Ungar said.

A bill in Congress called the Affordable HOMES Act, a Republican-sponsored measure that is advancing with the support of some Democrats, would roll back the Department of Energy’s most recent attempt to update the standards and block the agency from setting future ones.

Proponents contend that stricter standards will make new homes cost more for consumers, an argument that Ungar said is outweighed by the larger savings on energy bills, which result in lower monthly costs even with a slightly higher mortgage.

“It is beyond frustrating that this has dragged on now for, depending how you count, 30 years since the energy code was last updated and 18 years since Congress told the Department of Energy to fix the problem,” Ungar said. “Every year, there’s tens of thousands of new homes that stick their residents with these bills for the decades that people are in those homes.”

Parris blames the poor insulation in her 1970s home for leaching cool air in the summer. She’ll set her air conditioning to 77 degrees, but the temperature inside rises to around 87.

Duke representatives have told her that her new air conditioning may have been installed improperly, Parris said, and have explained that her kilowatt usage is double what they would expect of a home her size.

Poor insulation exacerbates costs that are already rising because of hikes to base rates and — particularly stark this year — steep hurricane recovery fees from 2024’s disastrous season.

Why Tampa Bay electric bills were so high in 2025

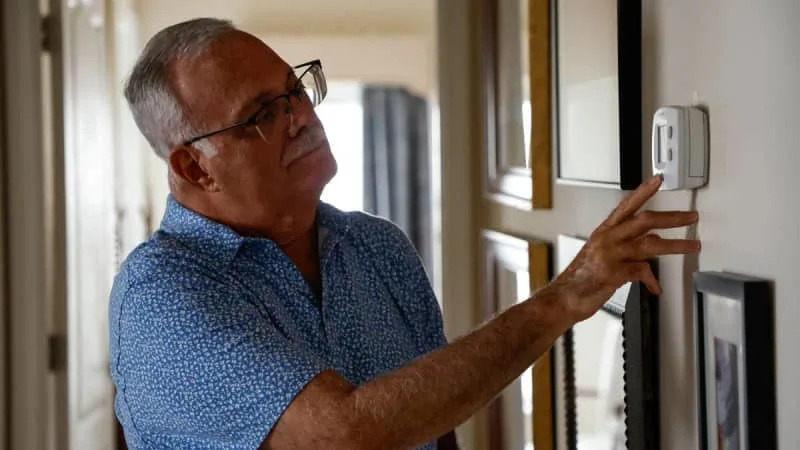

Brad Coath paid more when he bought his mobile home to get it upgraded with extra insulation. It’s paid off, he said, as he’s noticed it holds its temperature well in the summer. Still, Coath, a 66-year-old retired nurse, has seen the bills for his St. Petersburg mobile home swell.

He’s enrolled in Duke’s budget billing program, which averages out bills across each quarter to make them more predictable. They went from around $150 to over $200 this summer, prompting him to cut back on travel and put off bigger expenses.

“I get so tired of the PSCjust rubber-stamping everything that comes across their desks,” Coath said, referring to the Florida Public Service Commission that approves utility hikes. “Do these people not get bills? How do I get that job?”

Duke Energy has emphasized that the storm cost recovery charge, which is around $32 monthly for a household using 1,000 kilowatt-hours, will fall off bills in March, which is also when a separate seasonal discount kicks in. Tampa Electric’s hurricane fee, which is about $20 per month for the same energy use, will last longer, until September 2026.

Both companies noted they have programs to help mobile home residents improve their efficiency, like home energy audits that can lead to discounts. Duke, for example, offers rebates up to $600 for air conditioner replacements to qualifying mobile homeowners, and smaller rebates for duct repair. They are funded by all Duke customers through a charge on their bills.

Edward Cifelli, 83, moved to Dade City with his wife almost 20 years ago because the rolling pastureland reminded them of their longtime New Jersey home.

Electric bills for their double-wide usually hover around $200, an amount they can manage even as the rent for the lot their home sits on continues to creep upward.

But in August, their Duke bill hit $300 for the first time Cifelli can remember. He doesn’t understand why utilities charge residents for hurricanes when those should be an expected part of doing business in Florida.

“It doesn’t seem right to me that we pay a certain amount of money, and when it gets a little expensive for them, they make us pay extra,” he said. “Old people are always concerned about outliving their savings, and that’s where we are.”

• • •

The Tampa Bay Times launched the Environment Hub in 2025 to focus on some of Florida’s most urgent and enduring challenges. You can contribute through our journalism fund by clicking here.