As part of the Orlando Sentinel’s 150th birthday this year, we’ve asked former staffers to write about memorable stories they covered during their time at the newspaper and give some behind-the-scenes insight into how the stories came together. Today, former Sentinel reporter Gerald Shields (1991-97) shares his memories about an Orlando-bound train for the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus that detailed in 1994, killing two members of the circus.

It’s January 13, 1994. I’m scheduled to work the 2-10 shift, covering an Orange County government meeting when the phone rings three hours early. I answer to the panicked voice of my editor, Wendy Spirduso.

“Shields,” she says. “Get in here. A circus train crashed.”

I laugh.

“Right, and sixteen clowns spilled out of a Volkswagen.”

She doesn’t.

“I’m serious,” she says. “A couple people are dead.”

By the time I reach the Sentinel newsroom, I’m drafted as rewrite man on what would become the worst train crash in the more than 100-year history of the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus.

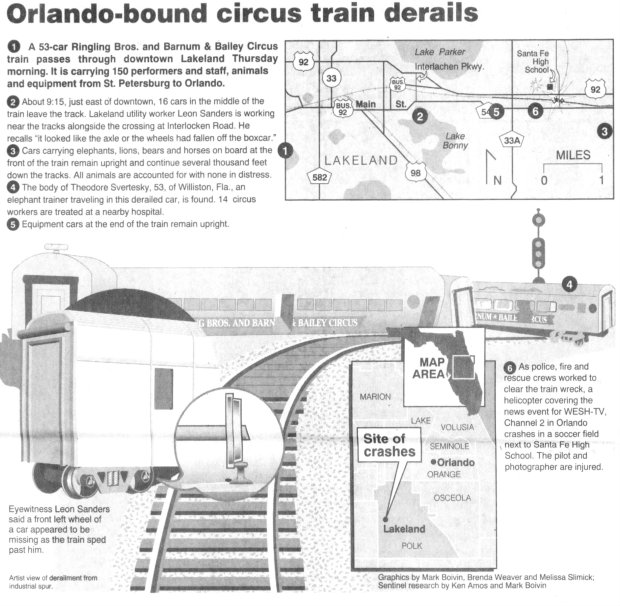

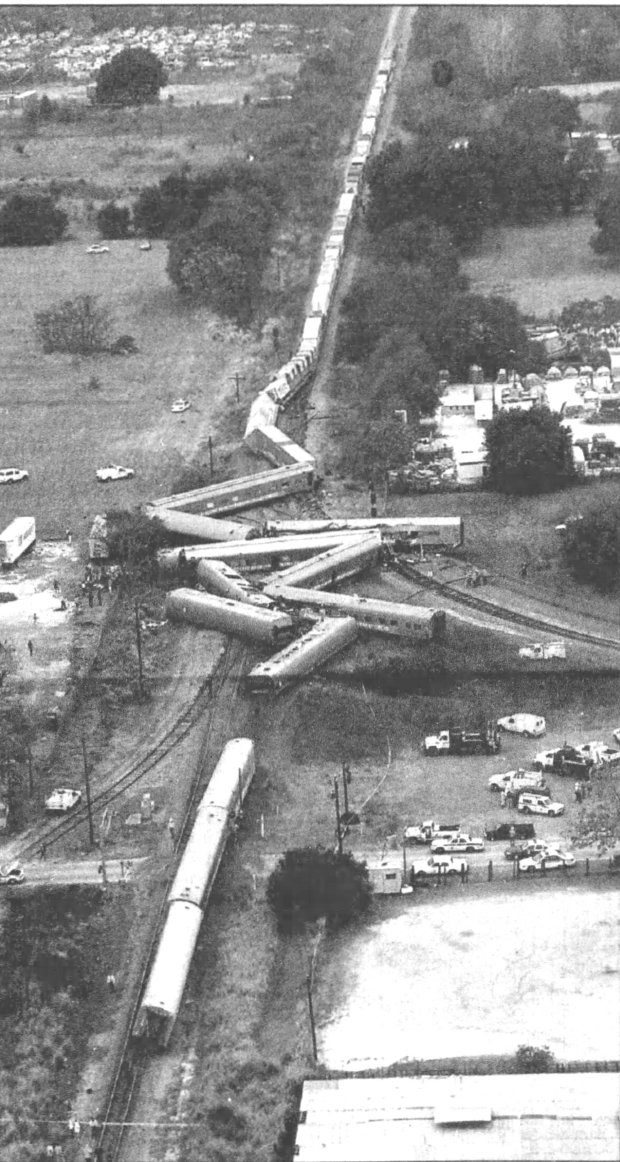

Fifteen cars had jumped the tracks as the caravan chugged north from Lakeland, bound for six scheduled shows in Orlando.

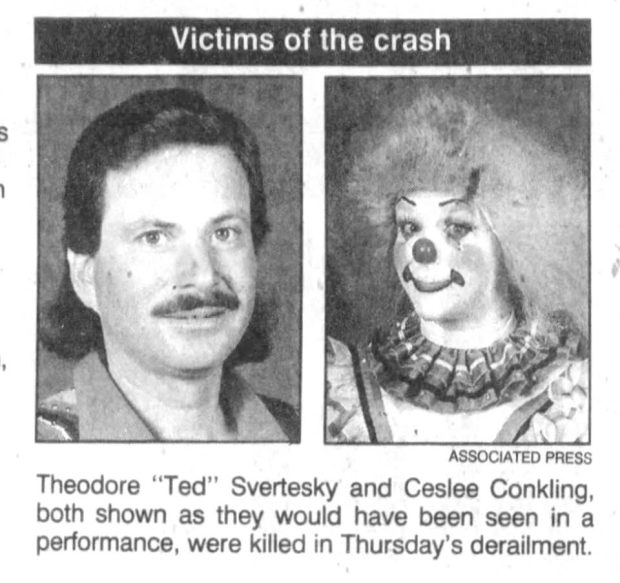

Fastball dispatches fly in from a platoon of reporters fanned out at the crash site. A 39-year-old elephant trainer is dead. So is a 28-year-old clown.

The two members of the circus who were killed in the 1994 crash. (Sentinel file)

The two members of the circus who were killed in the 1994 crash. (Sentinel file)

The town’s first jolt of fear was primal: that lions, tigers, bears, and elephants had escaped, turning rural Orange County into a safari. The animals were secured.

Henry Pierson Curtis — our revered police reporter — called with the first eyewitness account. He’d tracked down a scrapyard worker who saw stunned circus performers emerge from the fog.

“A little midget came by with scratches on his face,” David Smith told him. “He said he was walking between the cars when it derailed and it throwed him off the train. He was lucky.”

Orlando Sentinel graphic explains what happened with the train derailment. (Sentinel file)

Orlando Sentinel graphic explains what happened with the train derailment. (Sentinel file)

The phones lit up the next day with angry readers admonishing us over the word midget. “They’re little people,” one caller barked.

A quote, however, is a quote.

The ground reporting was stellar. The team even nailed the critical detail behind the wreck: a broken train wheel. Now a national story, we kept our foot on the accelerator.

I stationed myself on a street beside the tracks where shaken performers wandered to a convenience store for warm coffee in unusually cold Florida weather where the temperature dipped below freezing. None of them would talk.

In this 1994 photo, railroad cars lie scattered in Lakeland after part of the Orlando-bound circus train with 53 cars derailed. Witnesses said they saw a boxcar lose a wheel. (Sentinel file)

In this 1994 photo, railroad cars lie scattered in Lakeland after part of the Orlando-bound circus train with 53 cars derailed. Witnesses said they saw a boxcar lose a wheel. (Sentinel file)

Unbeknownst to me, a tussle was brewing in the newsroom. Top editors wanted to hand the story to Mike Thomas, our superstar writer. Spirduso stood her ground, insisting I had the chops to deliver.

Learning of their doubt lit rocket fuel under me.

Circus officials allowed me to join the traditional parade through downtown Orlando from the train to the Centroplex. Elephant tails swayed. Tightrope walkers waved. Sidewalks filled with cheering fans willing the battered troupe forward.

2 killed in crash of Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Baily Circus train

Despite nearly losing everything just two days earlier, the circus lived by the oldest creed in show business: The show must go on.

They had lost everything in the wreck – costumes, belongings, even clothes. Ticket holders were asked to bring donations. I filled a trash bag with sweaters and sweatshirts to shield them from the cold and hauled it to the arena, Santa with a sack.

In the basement, tables stretched wall to wall, piled high with clothes donated by kind Orlando residents.

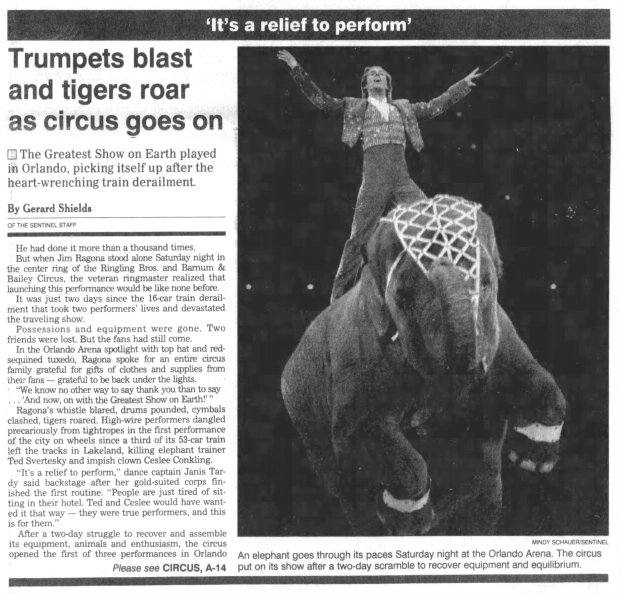

Coverage of the opening of the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus in Orlando after the 1994 train crash. (Sentinel file)

Coverage of the opening of the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus in Orlando after the 1994 train crash. (Sentinel file)

That night, I was allowed to stand on the floor near the center ring. The lights dimmed, the ringmaster stepped forward, a spotlight drenched his rainbow top hat and tails. Then he spoke the magic words.

“Ladies and gentlemen, the greatest show on earth.”

The National Transportation Safety Board took over the investigation. In those days, final findings took a year. I knew most reporters would move on to the next story. I didn’t.

When the report was released, I had the story to myself.

The NTSB found that the circus had violated multiple safety regulations. The wheel – just as we’d first reported – had split after exceeding its useful life. It was allowed to remain in service because it predated newer safety regulations.

The emergency cord system that could have alerted engineers to the unfolding disaster had been disabled. But the most egregious failure was inside the cars: furniture was unsecured.

The clown was killed when a file cabinet flew across the car and crushed her. The elephant trainer was mangled by debris while sleeping.

I made one of the hardest calls of my career, to Fort Worth, Texas, to explain to a young woman’s parents how their daughter died.

• • •

By cruel coincidence, my article on the NTSB findings ran a week before the circus was scheduled to return to Orlando. Furious owners phoned Managing Editor Jane

Healy, demanding a retraction before opening night.

Healy stood her ground, diplomatically telling them to jump in Lake Eola.

Thirty-one years later, I still get chills recalling the ringmaster opening the show after the crash.

Their dedication to their craft, walking the high wire, taming the caged lions and tigers, splashing front-row fans with confetti was a testament to the American spirit, the stubborn, defiant grit that has powered our nation since its inception.

Because on at least one night in its century long history, it really was the greatest show on earth.

After Shields left the Sentinel, he was a journalist for the Baltimore Sun, covered Louisiana in Washington for the Baton Rouge Advocate and ended his career as Washington correspondent for the New York Post. He has also written books with his last being a 2021 memoir on his newspaper days called: “The Front Row: My Jagged Journey Recording American History from Reagan to Trump.”