He’s an admitted drug trafficker, money launderer, smuggler and former fugitive, targeted for death after he flipped on Pablo Escobar’s cocaine empire in the 1980s, according to his own sworn testimony.

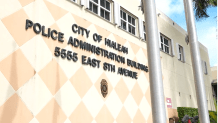

But his most lucrative seemingly legitimate score may have come as a confidential informant for Hialeah Police, who paid him at least $642,000 to lure cocaine buyers into their traps from 2014 into 2021, according to confidential police records obtained by NBC6 Investigates.

That was his share of more than $2.7 million those records reveal was confiscated from people he steered to a Hialeah warehouse to buy cocaine – only to have the Hialeah SWAT team rush through a door and arrest them once the deals were done.

How an informant who flipped on Pablo Escobar became Hialeah Police’s biggest cash cow, adding millions to the pool from which the police chief allegedly stole hundreds of thousands of dollars. NBC6’s Tony Pipitone reports.

During those years Hialeah Police deployed the confidential informant, $2.2 million in cash was deposited into bank accounts owned or controlled by its then-police chief, Sergio Velazquez, according to an affidavit in support of Velazquez’s arrest last month on grand theft and organized fraud charges.

NBC6 Investigates traced some of the cases cited in that affidavit directly to cases brought by the confidential informant, or CI, who we’ll call “Jose” to protect his and his family’s identity.

His work led to the arrests of about 115 suspects who, police say, thought they were buying their share of more than 150 kilos of cocaine he offered to sell.

How an informant who flipped on Pablo Escobar became Hialeah Police’s biggest cash cow, adding millions to the pool from which the police chief allegedly stole hundreds of thousands of dollars. NBC6’s Tony Pipitone reports.

Such operations – called “reverse stings” – are perfectly legal, prosecutors have argued when opposing charges being dismissed, as long as they do not involve entrapment, coercion, threats and the like. And CIs are allowed to receive a share of the cash seized, as long as it’s not contingent on their testimony in court or a successful prosecution, according to Florida cases those prosecutors have cited.

Jose’s action as a CI have not resulted in allegations of any criminal wrongdoing on his part.

But now some of his cases are being called into question after a Miami-Dade assistant public defender presented evidence Jose concealed a family secret – one that, once shared with prosecutors, led the state to dismiss several charges he brought to police.

THE MONEY MACHINE

A review of city budget documents, “confidential informant logs,” vouchers and payment records from Jose’s cases obtained by NBC6 Investigates shows his reverse stings were the largest source of cash forfeitures attributed to the department from 2017 through 2021.

He was a primary driver of the Hialeah police forfeiture money machine, its proceeds often winding up in Velazquez’s office suite safe, according to the affidavit for Velazquez’s arrest. It states only Velazquez, and a major, had continued access to that safe from 2016 until Velazquez was let go by a new mayor in November 2021.

In all, $3.6 million in Hialeah police cash — $1 million of it seized from drug suspects — is missing or unaccounted for during Velazquez’s tenure as chief from 2012 to November 2021, according to the Florida Department of Law Enforcement.

Velazquez has pled not guilty and, through his attorney, has declined comment.

An attorney representing Jose said the informant would have no comment, as well.

“ENTRAPMENT AND OUTRAGEOUS POLICE CONDUCT”

But Jose’s actions and alleged deceit have sent tremors rippling through Miami-Dade’s criminal justice system, with at least two people arrested in Hialeah’s reverse stings claiming they were Jose’s targets and seeking to have their convictions thrown out.

And they’re basing their arguments on facts that may have never come to light if not for the suspicions of one of the women Jose lured to Hialeah and the diligence of Miami-Dade assistant public defender Matlin Brown.

“I think the most important thing that she found was the level of corruption,” said her boss, Miami-Dade Public Defender Carlos Martinez,”…where what the police department was doing was actually creating crime” by entrapping people.

Brown said the steady parade of Hialeah cocaine trafficking set-ups made her suspicious, especially because Hialeah Police and prosecutors refused to identify the informants they were using or answer lawyers’ questions about them.

She then set out to identify one especially suspicious one who set up one of her clients, but, she said, met more resistance from police and prosecutors.

“This was something that kept me up at night for sure,” said Brown. “How do we have so many of the same types of cases, almost the exact same set of allegations, same lead-up, same process and nobody’s catching onto it? It seems suspicious.”

“We have a scheme to bring people in, to entrap people and then to funnel money to the Hialeah Police Department where that exact money is being (allegedly) pocketed by their police chief,” Brown said.

She said she spent countless hours chasing down leads and hunches to unearth facts and evidence that persuaded prosecutors to drop charges against her client once she revealed to them what she uncovered: “entrapment and outrageous police conduct,” as she titled her motion to dismiss the charges against her client.

No judge would have to rule on it, as prosecutors dropped cocaine trafficking charges against her client and three co-defendants four days after she filed the motion in December 2023.

It lays out evidence to support what the defense contends was Jose’s latest deception: failing to reveal a man he called “Pablo” who helped him reel in prospective cocaine buyers was not a “broker” – as his Hialeah Police handlers say they were told – but rather his brother in Colombia. And Brown’s client swore in the motion Pablo admitted to her he, too, was getting a cut of the money.

Jose, she said, was “not supervised by the police department … he’s subcontracting out that informant work essentially, and he is entrapping people, bringing people into a scheme for the benefit of, at least in our case, his brother (Pablo) and for the benefit of the Hialeah Police Department.”

But Hialeah Police and prosecutors claim ignorance.

In a deposition, the Hialeah Police officer who handled Jose testified he was a very reliable source and that Jose “had no idea” who Pablo was and “never communicated with” Pablo the broker.

According to police depositions, Pablo and other brokers named in their affidavits referred buyers of cocaine to people they thought were suppliers but were actually Hialeah Police informants. The brokers, they said, would expect to get paid a commission by the buyers once the deals went through or the drugs were sold for profit.

Brown said if police were lied to by Jose, “then, yes, he absolutely deceived them,” but if the police were in on it, “they deceived all of us … under oath.”

Public defenders are not the only attorneys who said what Brown found destroys any credibility Hialeah’s cash machine ever had.

Under the newly revealed circumstances, “Pablo” in Colombia “is just as much an informant as the one who’s actually in Miami,” said attorney Leonard Fenn, and would be subject to the same stringent requirements as a CI that his brother swore to uphold. “In my opinion that out-of-country person would be a partner of the informant, especially if he received some of the money that the informant received.”

Fenn said he wished he knew about Jose’s alleged deception when he was able to get Jose on the stand in a federal case involving another Hialeah police sting Jose orchestrated — one of the only times the informant was ever forced to testify under oath.

“I wish I would’ve known that when I went to trial,” he said of the case where his client was convicted, though of a lesser charge than the government sought. Knowing what he knows now, he said, “in my mind makes it more likely that this was a dirty deal.”

One that also had its roots with a mysterious “broker” from Jose’s home country of Colombia.

THE COLOMBIAN CONNECTION

The first steps on the trail Brown followed to clear her client, Jorley Holt, began in a city near Cali in southwestern Colombia where Holt has family.

A cousin of Holt’s was befriended online by a man Hialeah Police would call “Pablo,” who asked on social media if the cousin knew anyone interested in making money in the United States, according to Brown’s motion.

Knowing his cousin, Holt, was struggling in the real estate business in New York during the pandemic, he passed along her number to Pablo in May 2020, the motion states.

And that touched off several events that, lawyers tell NBC6, could constitute violations of the CI contract Jose signed with Hialeah Police in 2014.

For the next 12 weeks, Pablo or sometimes Jose repeatedly called Holt, who would block their numbers. Jose then used a new phone number to get her to answer, while his brother pleaded with Holt’s cousin to get her to call him or Jose, the motion alleging entrapment states.

The contract states he cannot “make constant contact nor encourage a subject with purpose of encouraging them to participate in an illegal activity.”

Holt was offered bargain-basement prices of $24,000 a kilo when supply chain bottlenecks and higher demand during the pandemic sent actual prices soaring toward $40,000 a kilo, a Hialeah Police sergeant testified in a deposition.

The contract prohibits CIs from offering “exorbitant profits, earnings or gains or compensation to cause the participation of a subject.”

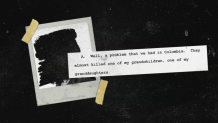

Holt continued to put off the CI and his “broker” until, she told Brown, “Pablo” sent her a photo of him with family members at their kitchen table in Colombia, followed by a video call where he displayed a gun, which she “reasonably interpreted as a threat against her family,” her attorney, Brown, recounted in her motion to dismiss.

The CI contract prohibits “threats to any subject or any person that is of importance to that subject.”

“That sends a very, very coercive message,” Brown said: “I have a gun around your family. I could hurt you. I could hurt your family.”

As the summer of 2020 progressed, Jose was trying to up the ante, Hialeah Police revealed in an affidavit. The bigger the deal, the more cash he would receive – money he testified in another case he does not report on his income taxes.

He tried to get Holt to bring $1.35 million to Hialeah to buy 50 kilos at $27,000 a kilo – from which he would be paid $337,500 by Hialeah Police at his standard 25 percent commission, but Holt made clear she did not have that kind of money, according to a Hialeah police affidavit.

So, Jose changed the pitch: She could buy 10 kilos and take another 10 kilos “on credit,” he offered, the affidavit states.

After weeks of Holt ignoring him, he got through to her and suggested four kilos at $27,000 each and Holt agreed to pay $100,000 for four to five kilos, according to Hialeah police.

On August 10, 2020, Holt and three men she brought with her were arrested during the staged buy with Jose and his undercover police handler at the Hialeah warehouse. Eight days later, Jose received $25,000 in cash from the $103,000 confiscated, according to the police records.

That was part of more than $235,000 in cash Hialeah paid him in the year after the pandemic began.

One thing missing from the arrest scene, Brown said, was Holt’s cellphone, which could have recorded evidence of the alleged entrapment and the threat she perceived from Pablo when he was with her family in Colombia.

Video taken seconds before Holt’s arrest clearly shows her holding a cell phone.

But the police property receipt for her arrest shows no such phone was collected from her. “And yet they’re saying, no, she never brought a phone to this transaction,” Brown said, citing a detective’s testimony that the absence of the phone on the property sheet means “she did not have a phone” though video clearly shows one in her possession.

“So something about the phone Hialeah wants that hidden,” she said, alleging in her motion “deliberate evidence tampering.”

A Hialeah Police spokesman said he does not have information on what may have happened to the phone and officers from that or other reverse stings have not responded to texts or calls seeking comment.

A STRIKING RESEMBLANCE

After her release on bond, the motion states, Holt contacted the man in Colombia posing as “Pablo” and, she said, he admitted he was not a broker who thought Jose was a source for cocaine in the Miami area – as Hialeah Police swore in an affidavit successfully seeking forfeiture of the confiscated $103,000.

Instead, she said, he admitted he was working with Jose and had been paid for connecting them – an arrangement that Brown and other attorneys say violated Jose’s confidential informant agreement with Hialeah Police.

“That’s not allowed,” said veteran defense attorney and former prosecutor Gustavo Garcia-Monts. “They have an obligation to make sure the confidential informant is following the rules that they set forth for the CI.”

Concealing that is “a violation of their rules. It also creates a due process problem. You do not know what the brother did to convince the target to call the individual in Miami,” he said.

The contract Jose signed as a CI states he must “report immediately to the investigators of narcotics section who I’m working with.”

But in depositions drug agents testified they thought the man feeding Jose leads was a “broker” – someone expecting to get paid a cut by the buyer of cocaine once the deal was done, essentially a criminal co-conspirator.

Then, during her video call with Pablo, something else occurred to Holt: Pablo bore a striking resemblance to and spoke with the same Colombian accent as Jose.

“She realizes they’re about the same age, they look similar, they have the same accent, and she started to wonder if maybe they might be related,” Brown recalled, adding Holt also learned from her cousin Pablo’s real first name, but not his last.

So Brown spent weeks investigating, searching records for Pablo’s real first name with the CI’s last name. That led her to court and prison records, newspaper articles, an obituary that listed both names as brothers, and finally a photo of Pablo under his real name – the same last name as Jose. Brown said she had her client look at the photo and confirmed: Pablo, it turned out, was not a broker, but rather a brother working with Jose to set up the stings for Hialeah police.

Brown said the revelation set off a range of emotions: “Excitement that we have the missing piece, that we found the missing piece. And also, frustration and kind of anger that this information wasn’t provided to us. This is something we have to dig for. This is something that took a lot of time and lot of luck to find out.”

It also destroyed the state’s case as, lawyers said, it made brother Pablo a sub-informant, an extension of Hialeah police’s star CI – a now 74-year-old longtime informant who, presumably, has been out of the cocaine trafficking business for decades.

Yet he claimed to have an active and wide network of different brokers, according to forfeiture records, giving Hialeah police in each of his cases a new supposed alias for the supposed broker, including: “Uncle,” “Carlos,” “Tony,” “El Abogado,” “El Calbo,” “Juan,” “Martine,” “Maria,” “El Mexicano,” “El Patron,” “J.J.,” “El Profe,” “Chachy,” “Tito,” “Cesar,” “Moises,” “Chava,” “Sergio,” “Boris,” “Boca Chica,” “Marino,” “Fernando,” “Miguel,” El Paisa” and, of course, “Pablo.”

“If we’re to believe the police officers, then he’s got friends all over the hemisphere” eager to send prospective cocaine buyers his way, Brown said with a hint of skepticism.

But if his brother was a source for several cases, lawyers point out, Jose would need to create false aliases for the “brokers.” After all, they said, real brokers would not repeatedly send potential clients to the same supposed supplier in Hialeah once they realized the referrals were being arrested and their money confiscated.

But someone getting a cut of the pie would have his reasons to do just that.

BROTHERS IN CAHOOTS

Jose the CI and Pablo the “broker” share more than genes and business.

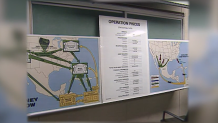

They were both arrested in 1987 in what was at the time the largest undercover cocaine trafficking and money laundering investigation in history, dubbed “Operation Pisces,” according to court records and press accounts from that time.

Its ultimate target: the notorious kingpin Pablo Escobar, for whom Jose has testified he trafficked cocaine and laundered money.

In exchange for his testimony against Escobar’s co-conspirators, Jose was granted leniency, serving only six years of a 10-year sentence, then given a new identity in the witness protection program in Missouri in 1993, according to testimony Jose gave in a federal case against another of the cocaine buyers he set up in Hialeah.

His brother, though, went to trial, was convicted of conspiracy and possession of cocaine with intent to distribute and was sentenced in 1988 to 25 years in prison, according to federal court records.

While Pablo did his time, Jose went back to committing crimes.

Unhappy living under an alias in witness protection in Missouri, he and his common law wife returned in 1996 to Florida, where he soon was convicted of smuggling stolen cars to Colombia, according to his testimony and court records.

Instead of reporting to prison in 1999 to serve his 21-month sentence, he admitted in a deposition he fled to Colombia and was a fugitive for nearly five years.

That ended in 2003 when his then-13-year-old granddaughter was shot multiple times in the spine, throat and shoulder by “narcos” in Colombia retaliating for Jose’s work with the DEA and others, he argued in court papers seeking a reduced sentence for his car smuggling conviction.

He also claimed in that motion he tipped off the feds to a plot to assassinate six DEA agents in Colombia while he was a fugitive there.

He turned himself in and, after his arrest, his daughter and granddaughter were allowed to move to the United States, where they remain today, while he went to prison, his term extended to 28 months.

Upon his release in 2006, Jose has testified he continued to supply information to the feds about boat and plane shipments of drugs coming from Colombia, adding he was not paid for that information, but – as an informant –is allowed to stay in the US despite his illegal immigration status.

He continues to live in Miami-Dade County today in a rented townhouse with his wife, who also declined to comment to NBC6.

As for his brother, “Pablo,” he was released from federal prison in 2009 and deported to Colombia, where – the public defender’s motion alleges — at some point he teamed up with his brother, feeding him phone numbers of potential targets, including Jorley Holt.

CHARGES DISMISSED

Brown, Holt’s assistant public defender, laid it all out for prosecutors in her December 2023 motion to dismiss — 328 pages of argument, allegations and supporting documentation that claimed Holt’s constitutional rights were violated by “outrageous police conduct.”

It mentioned how Hialeah Police swore “Pablo” the “broker” knew Jose to be a supplier of cocaine – when her investigation unearthed evidence they were brothers who would share in the spoils; how Pablo sent the selfie of him with Holt’s family in Colombia and flashed a gun; the weekslong badgering, despite numbers being blocked and calls not being returned; the artificially lowered prices Jose and Pablo offered that would’ve produced unusually high profits, given the going rate for cocaine during the pandemic.

All not just in apparent violation of the CI contract, but, she argued, signs of entrapment.

Informants are also told in their Hialeah Police contract not to “take advantage of the weakness of the subject, for instance…financial problems, with the purpose of leading them to participate in an illegal activity.”

But Pablo “was aware Holt was experiencing financial hardships” as a realtor two months into the COVID-19 pandemic when he first asked Holt’s cousin if he knew anyone in the United States interested in a “business opportunity,” the motion to dismiss claims. Multiple attempts to reach Holt for comment by email and phone were unsuccessful.

Four days after Brown filed her motion to dismiss based on entrapment and outrageous police conduct, prosecutors agreed to dismiss all charges against Holt and the three men arrested with her – all of whom faced a minimum 15 years in prison if convicted of trafficking more than 400 grams of cocaine.

(In all cases NBC6 reviewed, to reach that mandatory minimum sentencing threshold, Hialeah Police laid out for would-be buyers’ inspection a sliced open brick weighing more than 450 grams — part of a 26-kilo haul that had been stored in Hialeah Police buildings since it was seized in 1991, according to property records and an internal memo.)

That same state attorney’s office is now prosecuting someone they say walked away with about the same or possibly more cash than Jose, but they allege did so illegally: the former chief Velazquez.

As for those cash deposits totaling $2.2 million in Velazquez-linked accounts, each of the 922 deposits was under the $10,000 threshold that would require banks to report them to the government, the arrest affidavit states to support a third charge, money laundering.

His grand theft charge is a first-degree felony punishable by up to 30 years in prison because he allegedly stole over $100,000. Because such charges have a four-year statute of limitations and he wasn’t charged until June 2, 2025, the prosecuted amounts cover June through October 2021, a period when the affidavit states $635,652 in cash was missing or unaccounted for.

Jose was paid $642,986 for the time period documented in the records NBC6 Investigates obtained: May 2014 to February 2021.

HIALEAH DISCONTINUES REVERSE STINGS

In dismissing charges in the cases Brown brought to their attention, prosecutors documented scant information about why they acted as they did.

The office’s “closeout memos” usually give a detailed explanation of why a case is dismissed – citing facts and case law – but this one is only three sentences long.

It says Holt “filed a motion to dismiss alleging a variety of issues” and, after discussing the “allegations” with a top prosecutor, a dismissal “was deemed appropriate for all defendants.” But it never documents what those “issues” and “allegations” were.

State attorney Katherine Fernandez Rundle’s office will not comment on this or other cases where they used Jose to prosecute suspected drug traffickers.

Nor would it discuss how they would handle future cases involving the same informant or why others convicted or prosecuted based on Jose’s claims have not been notified of how he at a minimum deceived Hialeah Police to arguably violate Holt’s rights.

Hialeah Police tell NBC6 it no longer conducts reverse stings, the operations that allegedly fueled the former chief’s theft and fraud scheme. They were ordered stopped by the chief who replaced Velazquez, a department spokesman said.

A spokesman for the Miami-Dade State Attorney’s Office said, “no agencies in the county are bringing us cases involving reverse stings” any longer, adding, “We recognize that juries do not like reverse stings.”

But a review of court and Florida Department of Corrections records reveals dozens of people in prison or on probation because Miami-Dade prosecutors obtained plea deals or jury convictions from cases the deceptive informant Jose brought to Hialeah police.

And Brown said Hialeah or other agencies could still be using him, if not for reverse stings in some other sort of case. Hialeah police wouldn’t say whether they are still using Jose for any purpose. The city and police department have not answered detailed questions or responded to requests for public records on the stings or their officers for weeks.

The state continues to fight attempts to vacate convictions for those who, citing Brown’s work, say they were unjustly prosecuted because, while police were swearing Jose was a “proven reliable CI,” there’s now evidence he was also concealing material evidence: at least one of his “brokers” was his brother, who told Holt he was also being paid for his work.

And it all would have remained secret, behind Hialeah Police and the state attorney’s refusals to reveal information about or let defense attorneys question the confidential informant, if not for the persistent digging of Matlin Brown, a 2020 graduate of the University of Miami School of Law in her fifth year with the public defender’s office.

“For many months it’s one of those things that it’s in the back of your mind constantly,” she recalled. “You’re constantly trying to figure it out. You know that something is not right. You’re always trying to think of a different angle: How can I approach this? Where can I check? Where might I find this information that I’m looking for? Because you have the police department and you have the state attorney’s office telling you there’s nothing here, there’s nothing here. But you know there’s something else here and you’re going to have to find it yourself.”

Now that she did, other lawyers are using her work to argue that their clients were also trapped by Jose and should have their convictions vacated. One is appealing after a circuit judge in March denied his motion, noting he pled guilty and had never asked the state to disclose the confidential informant in his case, so there was no evidence it was Jose, the one in Holt’s case. Another is set for a hearing in Circuit Court next month.

But the state attorney’s office is not informing people they’ve convicted based on Jose’s work of what Brown uncovered, and that, she said, just adds to the injustice.

“There are people who are still actively suffering,” she said. “We’re not even talking about criminal records and probation, but people actually serving time, hard time over these cases.”