Just as NADA Miami opened downtown Tuesday, Untitled Art opened its fair on the sands of Miami Beach. The week’s two main satellite fairs both opened the day before the main gun in town, Art Basel Miami Beach, and have seemingly been duking it out for exhibitors, with Untitled trying to lure participants to its tent with the promise of higher foot traffic for collectors unwilling to make the traffic-laden trek across the causeway.

Having been to both fairs on Tuesday, that competition seems more healthy than nasty. Untitled historically attracts some closely watched galleries but often rounds out its tent with exhibitors whose presence makes you question the selection committee’s standards. Thankfully, there was less of that this year. Sure, a significant enough portion of the art in the aisles wasn’t for me, but plenty of that work will find buyers.

For this edition, Untitled has rejiggered its floor plan, with some galleries in the center row taking much larger booths than usual—perhaps to compensate for losing longtime exhibitors to Art Basel, which the fair touted in a pre-fair release. The fair also expanded to Houston this year, and one booth has been given over to a gaudy promotional sign for the city that would look much better left blank. The Nest section, which offers subsidized booths to emerging galleries, appears rotated roughly 45 degrees off axis from the rest of the layout. (If I had to guess, they took the “Nest” name literally.) While painting was in heavy force at NADA, Untitled offered a strong showing of fiber-based work and sculpture.

Below, a look at the best booths at Untitled Art, Miami Beach, which runs through December 7.

Omar Mismar at Secci

Image Credit: Maximilíano Durón/ARTnews

Beirut-based artist Omar Mismar has been making work about Palestine for several years, including Still My Eyes Water (2025), a hulking floral sculpture commissioned for this year’s Taipei Biennial. Since appearing in the 2024 Venice Biennale, his mosaic works have also earned acclaim. On view here is one of the fair’s most poignant works, a four-panel mosaic titled Ahmad with the sponge (2025). It shows different views of a floor mosaic in Gaza—including one in which a man cleans it with a bucket and sponge—that Mismar stumbled upon online, a recurring source in his practice. It’s unclear whether the original mosaic survived, but Mismar has ensured we won’t forget it. Nearby are four mosaics displayed on plinths, showing the torsos of men drawn from dating apps. Paired with Ahmad with the sponge, they take on an even more haunting resonance.

Lyndon Barrois Jr. at Alma Pearl

Image Credit: Maximilíano Durón/ARTnews

London-based gallery Alma Pearl has brought work by Pittsburgh-based artist Lyndon Barrois Jr., now a fellow at London’s Royal Academy of Arts. Barrois often uses film, art history, and historical narrative as his starting points. On one wall are three paintings, each with a solid background—royal blue, burgundy, and yellow—featuring schematic drawings of a die and collaged details of two hands. Above each canvas is a different set of color bars used to calibrate saturation in film and photography. The hands, sourced from art-historical passages including a Vermeer painting, each perform a different kind of sleight of hand.

Barrois’s work addresses the histories of colonialism, and this series obliquely references the story of George Washington Williams, born free in Pennsylvania in 1849, a Civil War soldier who later became a member of Ohio’s House of Representatives. In 1890, he visited the Congo Free State and was horrified by the abuses perpetuated by Belgian colonizers. His letter to King Leopold II denouncing these practices popularized the term “crimes against humanity.” Barrois links this exploitation in the Congo to the sleight of hand Belgium used to first gain access to the region—before establishing a brutal regime that killed millions. Today, extraction continues, as the world still seeks to mine Congo for minerals like cobalt used in lithium batteries.

Carlos Rolón at Hexton Gallery

Image Credit: Maximilíano Durón/ARTnews

Nearly the entire central wall of Hexton Gallery’s booth is covered by a white tarp painted by Chicago-based artist Carlos Rolón with black depictions of plants found in Puerto Rico. Above it hang three works that similarly use tarps—brown and blue this time—onto which Rolón has affixed familiar Puerto Rican Spanish idioms: “te necesito” (I need you), “ay bendito” (oh my God), and “¿qué pasa?” (what’s up?). Onto these tarps he has sewn vibrant wildflowers. Rolón sourced the tarps directly from Puerto Rico, working with a nonprofit that replaces them for residents; they have remained on roofs since Hurricanes Irma and Maria in 2017.

“Something that’s supposed to last six months has been there for six or seven-plus years,” Rolón told ARTnews during the VIP preview. At the back of the fair, near Untitled’s Podcast Lounge, Rolón has installed a large-scale work from this series that reads “Está Cabrón” (That’s hardcore). The degradation of the blue tarp from years of wind is visible.

Napoleón Aguilera at Palma

Image Credit: Maximilíano Durón/ARTnews

At the center of Guadalajara-based gallery Palma’s booth are five works from Napoleón Aguilera’s “Pesados” series. The title literally translates to “heavy,” but in Spanish can also mean “tough” or “hardcore,” and is often used to describe high-ranking cartel members. Drug lords have historically been stereotyped as wearing cowboy boots to signal masculinity, but many now favor designer shoes like Margiela’s Tabi. Aguilera presents both styles as sculptures. The literal meaning of pesado also applies: the works, carved from obsidian and volcanic stone, weigh a great deal.

Scott Hocking at Library Street Collective

Image Credit: Maximilíano Durón/ARTnews

Another standout special project is Scott Hocking’s Water Works (2025), an installation gathering water-related objects. The Detroit-based artist recently spent time combing through a marina in Michigan, pulling out and arranging items into an organized chaos of a shelf-like structure. The work, part of Hocking’s “RELICS” series, attempts to make sense of the layered histories of Detroit by sifting through urban detritus found in unassuming spaces like storage rooms at marinas. Here he assembles metal scraps, glass bottles, a blue-painted skull, driftwood, rope, wire fencing, and a heap of rusted bottle caps resembling barnacles.

Alice Quaresma at Pablo’s Birthday

Image Credit: Maximilíano Durón/ARTnews

One wall of this booth is devoted to Alice Quaresma, who melds photography and abstract painting. Now based in London, Quaresma was born and raised in Rio de Janeiro, and her works often distill childhood memories—sharp or hazy—shaped by that coastal landscape. Sometimes she collages small photographs onto much larger images; elsewhere, her marks, ranging from opaque to semi-translucent, sweep across the picture plane.

Juan Pablo Vizcáino Cortijo at Negrón Pizarro

Image Credit: Maximilíano Durón/ARTnews

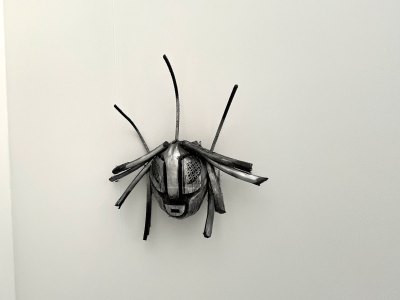

San Juan–based gallery Negrón Pizarro presents four artists—011668, Demetrio Kasper, Juan Pablo Vizcáino Cortijo, and Kivan Quiñones Beltrán—in a group presentation titled “Exit the Fiction of America,” focusing on contemporary notions of what it means to be American.

Vizcáino Cortijo’s sculptures use scrap metal from barges in Loíza. Inspired by the folkloric figure el vejigante, he has, since 2020, created “Vejigantes” masks that merge Afro–Puerto Rican mask-making traditions with a futuristic bent—imagining a path out of Puerto Rico’s colonial past into a new future.

“It is the year 2045 and I am protected by this mask that is itself a weapon. You can’t contaminate me. You can’t recognize me. And I can charge like an animal at any threat,” Vizcáino Cortijo once said in an artist statement about the series.