Small cameras that come with access to a massive national database and powerful software are a growing tool for South Florida law enforcement. Controversy comes with them, too.

License plate recognition cameras owned by the private technology company Flock Safety have increased in popularity in the past few years. The 8-year-old company describes the cameras as capable of being “placed almost anywhere to capture detailed data about license plates and vehicles used to commit crimes,” used by thousands of police agencies across the country.

When a car drives by a Flock license plate reader, the motion-activated cameras capture a clear burst of photos of any car passing by, a company spokesperson and local law enforcement officials told the South Florida Sun Sentinel. Detailed information is then retained in the system, beyond just a license plate number — including make, body type, color and characteristics such as window stickers or items in the bed of a truck. The software has a unique AI search feature, called “Vehicle Fingerprint,” that allows officers to search keywords and descriptions to find vehicles. Police departments can opt to share their data with other agencies locally, statewide or nationwide.

There are hundreds of these cameras across Florida, and multiple South Florida law enforcement agencies are currently using them, including the Broward Sheriff’s Office, Boynton Beach Police, Fort Lauderdale Police, Margate Police, Pembroke Pines Police, Coconut Creek Police and Davie Police. It is unclear exactly how many and which South Florida agencies currently use them; several police departments did not respond to requests for information before publication.

Critics, including the American Civil Liberties Union, say there’s too much potential for the system to be abused and that it invades privacy rights of citizens who aren’t suspected of any crimes, claims that the company refutes.

There have been mounting concerns since President Donald Trump took office about the data being used for federal immigration enforcement. The company’s database of license plate information has been searched hundreds of times for immigration-related enforcement this year across multiple states, including in Florida, according to news reports.

A Colorado software engineer has spent more than a year creating and maintaining a website that shows people where different types of automated license plate readers are located across the country, including some of Flock’s, with the message displayed on his homepage: “You’re being tracked.” Police agencies generally keep camera locations secret.

An automated license plate reader that appears to be a Flock Safety camera is shown on Northeast Fourth Avenue in Fort Lauderdale on Wednesday, Dec. 3, 2025. (Amy Beth Bennett / South Florida Sun Sentinel)

An automated license plate reader that appears to be a Flock Safety camera is shown on Northeast Fourth Avenue in Fort Lauderdale on Wednesday, Dec. 3, 2025. (Amy Beth Bennett / South Florida Sun Sentinel)

South Florida law enforcement officials say the cameras are among their most valuable tools for fighting crime and that they are used solely to investigate crimes, not to surveil people randomly around the clock.

The license plate readers were critical in helping solve a shooting investigation last summer that spanned multiple cities in Palm Beach County with the arrest of a man who kept a ledger of all of the addresses he targeted and had 10 more homes on his list, Boynton Beach Police Assistant Chief John Bonafair said.

As police departments struggle to recruit and retain officers, Flock’s license plate cameras are allowing agencies to do more police work with less, company spokesperson Holly Beilin told the Sun Sentinel. Increasingly, major cities are opting into the technology, she said.

Flock has responded to criticism on its website with a page detailing privacy and ethics, touting a “Transparency Portal” that allows police agencies to share data publicly about how they are using the cameras if they opt to do so, system audits and case law that deems license plate reader data constitutional.

Will Freeman, the creator of the plate-readers-mapping website and a staunch critic of Flock, was driving on a road trip from Seattle to Alabama when he noticed the cameras over and over, attached to poles alongside roads from smaller towns to major cities: Small black solar panels with a black camera attached. There was hardly any public discussion he could find about the cameras once he learned what they were, he told the Sun Sentinel, despite them being seemingly everywhere.

“I wanted to change that because I feel like if people knew what they were, they’d be creeped out by them,” Freeman said. “These things were introduced in most communities without any input.”

Despite the controversy surrounding them, the number of cameras in some parts of South Florida is likely to expand in the near future, two local law enforcement agencies told the Sun Sentinel.

How it works

The software on the cameras compares a license plate number against different national crime databases, including an AMBER alert database and the National Crime Information Center, NCIC, database maintained by the Department of Justice. If there’s a match, law enforcement will receive an alert in real time with information, including which camera the car passed, according to Beilin.

The license plate cameras do not use facial recognition, and the system does not directly identify personal information like who a vehicle belongs to or the person’s address, Beilin said. Police officers must find vehicle registration information separately, outside of Flock’s system. While concerns about privacy are “very real questions,” she emphasized that the cameras are making a notable difference in fighting crime.

Officers can also use the system for investigations. Beilin used the example of searching for a vehicle involved in a hit-and-run crash; if an officer has partial information about a vehicle, he or she could search for specific types of cars or characteristics. If a victim in a hit-and-run saw that the car involved was a white pickup truck with a license plate that began with the letter B or with a rack attached to the roof, as another example, Beilin said an officer could search for that “granular” information.

Bonafair said that AI feature of Flock’s software was at work in a recent illegal dumping case, where Boynton Beach Police searched the data to find items in the back of a pickup truck.

The police department had used other types of automated license plate readers for about six years while Flock’s cameras were installed within the past two, Bonafair said. The city has a total of 10 cameras, two going in opposite directions in each location, placed in areas based on “serious crime” data, and all of the department’s road patrol officers have access to the system.

“It’s one of those things where it usually doesn’t solve the case, but it usually helps us get to a point where we can interview people or develop leads,” he said.

To Bonafair, one of the most beneficial parts is the ability to share information with other police departments.

“If another agency is looking for a car, we can see if it went into other jurisdictions, they can see if it went into ours. They can ask for help … It allows us to network,” he said.

Each police department customer of Flock owns its respective data captured on the cameras, Beilin said, meaning Flock cannot sell it and the individual agency decides who they share it with and for what purpose.

‘Just images’ or ‘mass surveillance’?

Freeman is one of several to manage websites critical of Flock and its cameras. Another site allows people to search their license plate numbers to see if they may have been searched by a Flock customer, using audit logs obtained by public records requests. Yet another shares data sourced from police departments that have made their Transparency Portals public.

Freeman said despite police department policies, officers could still be using the system for “searching on a whim.”

“The people with access to them aren’t perfect,” he said.

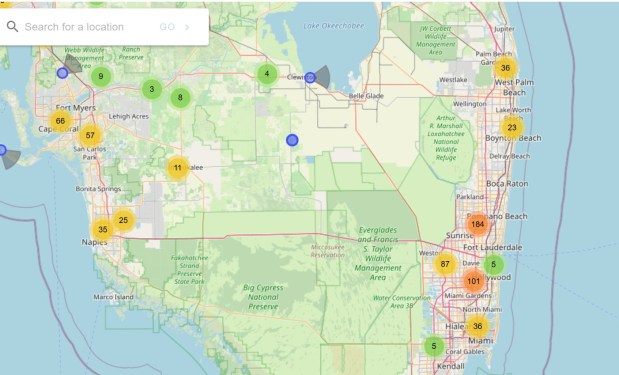

Various types of automated license plate recognition cameras are shown on a map, with locations based on crowd-sourced information. The clusters show the number of cameras reported in an area, some of which were identified by users as Flock cameras. (Will Freeman/Courtesy)

Various types of automated license plate recognition cameras are shown on a map, with locations based on crowd-sourced information. The clusters show the number of cameras reported in an area, some of which were identified by users as Flock cameras. (Will Freeman/Courtesy)

There have been two recent reports of mistaken identity related to Flock’s license plate cameras, a woman wrongfully accused of theft in Colorado and a man in Washington. And while police departments have their own policies and the company has an audit process in place to try to prevent misuse, there are several recent cases where law enforcement officers have been accused of abusing their access to Flock’s cameras, according to news reports. Most recently, a Georgia police chief was arrested last month after allegedly using Flock’s license plate system to harass and stalk multiple people, WSB-TV reported.

Flock has system audits in place that can uncover misuse when an agency does an internal investigation, Beilin said, which are “indefinitely saved” and are “unchangeable,” and all officers have to enter a reason for their search.

The company is implementing a feature this month where officers will have to select a reason for their search from a drop-down menu of crimes categorized by the National Incident-Based Reporting System, NIBRS, rather than entering their own text.

Boynton Beach Police’s policy on license plate readers says all information gathered from the systems will be for official law enforcement use only. It prohibits officers from pulling a driver over without confirming the alert received from the system and that an audit will be done semi-annually, in part, to identify if anyone is “abusing” the system.

The company has come under scrutiny in recent months after news reports in multiple states detailed how Flock’s database has been used for federal immigration enforcement.

“Policymakers need to recognize that the boundaries between local surveillance and the Trump Administration (as well as malevolent administrations in other states) are porous and hard to maintain — that if you collect local data on your residents’ comings and goings, it will be hard to keep that from being used in unintended ways,” ACLU Senior Policy Analyst Jay Stanley wrote in an August commentary about increasing criticism of Flock.

Florida Highway Patrol troopers performed more than 250 immigration-related searches in Flock’s license plate reader system in a two-month span earlier this year, an analysis by Suncoast Searchlight found.

More than 300 police departments in Florida have formal agreements with ICE to carry out some aspects of federal immigration enforcement, including FHP.

Outside of Florida, there have been instances of Flock’s database being used for immigration-related searches in Illinois, Kentucky and Virginia, according to news reports.

Florida troopers tapped surveillance network for immigration searches

In Illinois, the secretary of state recently conducted an audit of Flock’s data sharing and discovered that the company allowed U.S. Customs and Border Protection access to Illinois license plate data, which was a violation of a state law that restricts law enforcement collaborating with ICE without a court warrant, according to an August statement. Flock discontinued its “pilot program” with Border Patrol and other federal agencies nationwide as a result of the audit, Secretary of State Alexi Giannoulias said in the statement.

Kentucky and Virginia are among the 34 states across the country where local law enforcement agencies have entered agreements with ICE. Those two states do not appear to have any laws similar to the one in Illinois.

As of December, Flock does not have contracts with any agencies under the Department of Homeland Security, including ICE or Border Protection, however, “in states where it is legal and accepted for local agencies to collaborate with federal authorities, they do do so,” Beilin said.

In response to recent news reporting, in part, about immigration-related searches, Flock CEO Garrett Langley said in a June statement: “In some states and jurisdictions, local law enforcement work with federal authorities to enforce immigration offenses. In other states and jurisdictions, that is illegal per state law or considered socially unacceptable. The point is: it is a local decision. Not my decision, and not Flock’s decision.”

Flock has implemented a feature that allows a police agency to block other agencies it shares data with from conducting searches for civil immigration enforcement or reproductive healthcare, Beilin said.

Despite that filter being in place and having prevented “thousands” of other searches, one Illinois police department’s cameras were still accessed in more than 200 searches by police departments in other states for immigration purposes, according to a statement from the Village of Mount Prospect, Illinois.

Boynton Beach Police are not using the license plate cameras for immigration-related enforcement in “any way, shape or form,” Assistant Chief Bonafair said.

An automated license plate reader that appears to be a Flock Safety camera is shown on Northeast Fourth Avenue in Fort Lauderdale on Wednesday, Dec. 3, 2025. (Amy Beth Bennett / South Florida Sun Sentinel)

An automated license plate reader that appears to be a Flock Safety camera is shown on Northeast Fourth Avenue in Fort Lauderdale on Wednesday, Dec. 3, 2025. (Amy Beth Bennett / South Florida Sun Sentinel)

Bonafair said anyone with concerns about the cameras should know: “These are just images.”

“You also have to understand that, yes, it is taking pictures of the vehicles that pass by, but we’re not monitoring them live,” he said. “We’re not sitting there watching it. These are things that we’re only looking at the stuff if we’re looking for a suspect or something … It’s very hard to say that we are surveilling anything because we’re really not.”

There’s some degree of secrecy surrounding use of them locally. Multiple police agencies said they could not disclose how many cameras they use or their locations, citing security and investigative reasons.

“The Pembroke Pines Police Department currently uses Flock camera systems for public safety and investigative purposes,” said Pembroke Pines Police Assistant Chief Carlos Bermudez in a statement. “Unfortunately, offering more specific information could compromise our agency’s ability to effectively utilize this technology to its maximum potential. Therefore, this is the only information we will be sharing at this time related to our use of Flock cameras.”

Several cities that contract with BSO use the cameras, spokesperson Carey Codd said in a statement.

“For operational and security reasons, BSO does not publicize where LPR’s are placed in its jurisdictions,” Codd said. “Giving criminals and those with criminal intent the locations of the LPR’s would undermine the effectiveness of the cameras and potentially compromise the safety of Broward County residents and visitors.”

Freeman said the quiet nature surrounding use of the cameras, with often little to no public input from the community where they are installed, is one reason why he’s against them. And another: “I just don’t want to be tracked all the time.”

“I hear the arguments for the other side. I know crime is a thing, it always will be. But there are other ways … I don’t see why you have to install a mass surveillance system across the entire United States,” he said.