When people organize and speak with a clear, compelling voice, change happens.

People in Fort Lauderdale fought to protect part of the city fabric, its beloved beachside basketball courts, from the relentless march of a bulldozer — and they are winning, for a change.

The $2 billion makeover of Bahia Mar, the city’s most prized public space, included four trendy pickleball courts on the site of the existing basketball courts, which the developer would pay to move further south.

That aroused the public to a fever pitch to stop the destruction. By standing up for beach basketball, people were defending tradition and a defining part of the city’s character. They also proved that elected city leaders grossly underestimated the public’s emotional attachment to the courts.

‘Deferred,’ indefinitely

On Tuesday, they noisily crowded a commission meeting, for a vote to move ahead on the courts’ relocation. So many people insisted they stay put that the city deferred a decision — “indefinitely,” Mayor Dean Trantalis said.

It wouldn’t have happened without a public outcry.

This movement has many faces: Dan Santoro, whose first spring break trip was in 1979. Sally Alshouse, a lifelong city resident. Tracy Powell. Chris Nelson. Nancy Thomas. Susan Peterson. “Beachchair Greg” Risley. Devin Thomas. Barbra Stern. Chris Stachowski. John Rodstrom III, and more.

“Your mission is to serve the public, not the developers,” Christine DeMarco told commissioners.

“The beach isn’t yours to give away,” resident Vicki Mowrey told them. “You never had any public outreach on this … you can stop this.”

City of Fort Lauderdale

Dana Coronato of Fort Lauderdale pleaded with the city to leave its beachside basketball courts alone on Dec. 16, 2025.

Dana Coronato grew up playing on those courts. She played college basketball at Catholic University in Washington D.C. and is now a digital strategist and market researcher.

She said encouragement from male players on those courts gave her the confidence to succeed in life.

They said, “You deserve to be out here. You deserve to crush it. What do I do? I go out in business, and I crush it. I speak up. I come to meetings, and I stand up. I learned that from my community.”

A done deal? Not quite

The city approved the Bahia Mar deal at a meeting on Jan. 9, 2024.

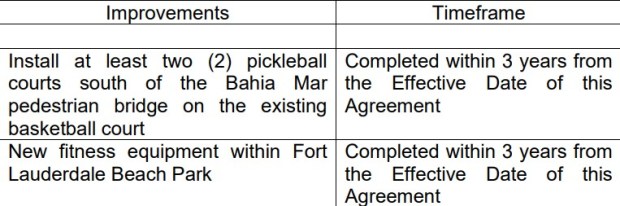

Buried in the paperwork was an 18-page contract between the project’s oversight board, the Bahia Mar Community Development District (CDD), and the city. It spelled out various terms, including a three-year timetable to convert the courts to pickleball. (The official description is wrong; the document says the courts are south of a pedestrian bridge when they are north.)

Few people, if any, noticed the language at the time, as the debate focused on air rights and the 240-foot height of the four condo towers. Former Commissioner Warren Sturman tried to call up the deal to debate it and change it, but no one supported him.

Fort Lauderdale

Fort Lauderdale

This sign spawned a grass-roots movement to save beach basketball in Fort Lauderdale.

This sign spawned a grass-roots movement to save beach basketball in Fort Lauderdale.

Only much later, when the city put up a sign about a planned “conversion” of the courts to pickleball, did people realize what could happen.

The sign was a pathetic excuse for real transparency. But in this case, it did the trick.

People circulated petitions (at the latest count, 8,874 signers) and used social media to mobilize an army of supporters.

We added our voice: “Keep basketball on the beach,” we said in a May 6 editorial, noting that this was yet another case of private profit overwhelming public access. “A bad deal,” we wrote.

After Tuesday’s outpouring of opposition, Trantalis said: “When the public speaks up, we need to listen.”

Joining the mayor in voting to defer action were commissioners Pamela Beasley-Pittman and Ben Sorensen.

The beach-area commissioner, Steve Glassman, voted to defer, as did John Herbst, but Glassman was uncharacteristically subdued on an issue affecting the heart of his district. Rather than vocally support his constituents, he cited the risk to the city by reneging on the courts’ relocation.

The risk appears to be low. That 2024 agreement has language protecting the city. It says changes to improvements require the CDD’s approval, “which shall not be unreasonably withheld,” a phrase emphasized by City Attorney Shari McCartney.

The developer’s promise

In a statement to the Editorial Board Thursday, the Bahia Mar developer, Jimmy Tate, promised “a good-faith effort to agree upon a mutually acceptable solution that serves the best interests for all of Fort Lauderdale.”

To all the residents who show your love for this great city by fighting to save beach basketball, we say, don’t stop now.

As every basketball player knows: Never quit. Start a crusade to save public land, and remind elected officials that you run Fort Lauderdale — not them. Aim higher to save what’s important, and carry it through to the next city election and beyond.

The Sun Sentinel Editorial Board consists of Opinion Editor Steve Bousquet, Deputy Opinion Editor Dan Sweeney, editorial writers Pat Beall and Martin Dyckman, and Executive Editor Gretchen Day-Bryant. To contact us, email at letters@sun-sentinel.com.