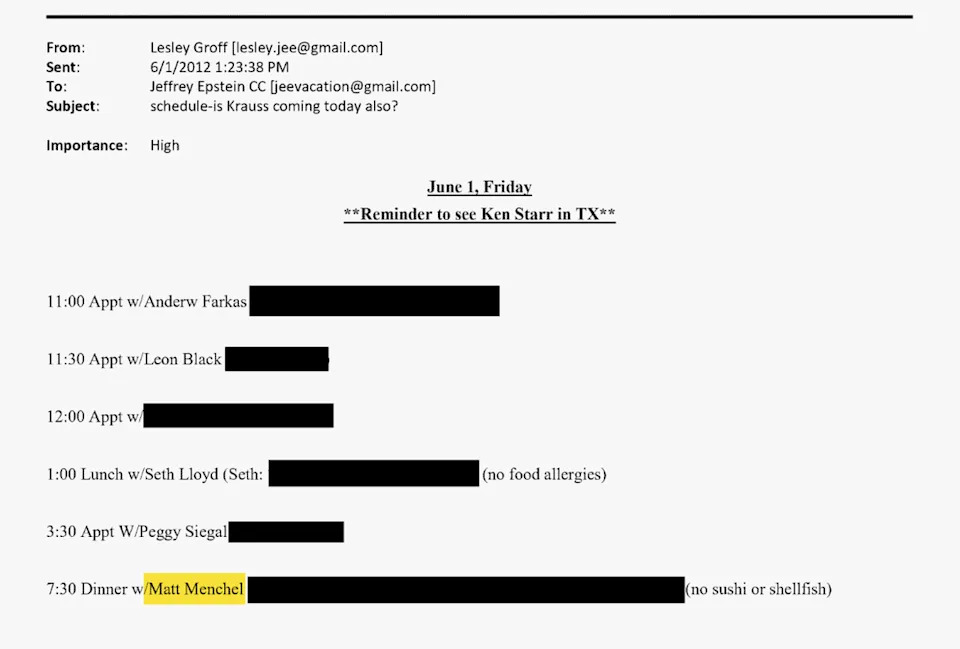

Jeffrey Epstein had multiple appointments, phone calls and dinners with Matthew Menchel — the Miami U.S. Attorney’s office chief criminal prosecutor who spearheaded Epstein’s sweetheart deal in 2007, newly released documents show.

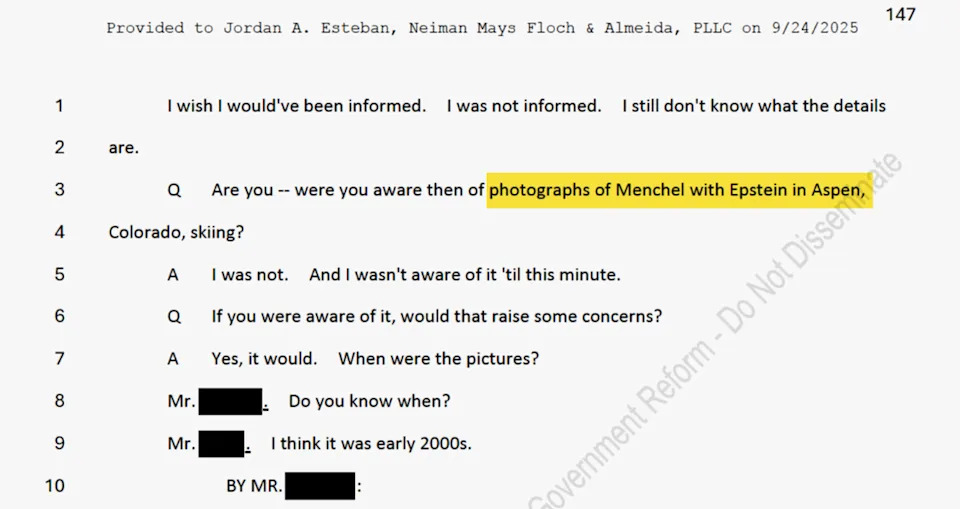

A tranche of over 8,500 pages of records from Epstein’s estate — released by the House Oversight Committee Friday — show that Epstein’s calendars and emails reflect that Menchel, who left the DOJ in 2007, had multiple meetings or dinners with Epstein in 2011, 2013 and 2017. Lawmakers also referred to a photograph of Menchel on a ski trip with Epstein sometime in the 2000s, but didn’t produce the photo.

Contacted on Friday, Menchel initially referred the Miami Herald to a 2020 statement he had previously sent the Herald in response to questions about whether he had a business relationship with Epstein.

“I had no business relationship with Mr. Epstein at any point, not before, during or after my tenure at the US Attorney’s Office.” He added that Epstein had tried to get his firm to handle some of the civil litigation associated with his case, but “we declined.”

After publication, Menchel told the Herald that he never skied with Epstein.

He did not deny that he had met with Epstein after he left the US Attorney’s Office.

Epstein’s 2008 deal allowed the New York financier to escape federal sex trafficking charges that could have put him in prison for life. It also gave immunity to others involved in his crimes, many of whom have never been identified. A 2018 investigation by the Miami Herald, called ‘Perversion of Justice,’ detailed how federal prosecutors in South Florida minimized Epstein’s abuse of almost 100 underage girls and worked closely with Epstein’s high-powered attorneys to keep the scope of his crimes secret.

Following publication of the series, federal prosecutors in New York re-examined the case, and Epstein was arrested again in 2019 on more serious sex trafficking charges. However, he died nearly a month later in federal custody, in what was ruled a suicide by hanging.

Friday’s revelation about Menchel comes as the House Oversight Committee continues its probe into the case. Lawmakers are examining whether there were other wealthy and powerful men who were involved in Epstein’s crimes and whether there was a cover-up by the FBI and Justice Department. Several banks are also under scrutiny for failing to flag financial transactions even though they knew Epstein had been accused of sex trafficking minors.

E-mail message showing that Jeffrey Epstein was scheduled to meet with Matthew Menchel.

President Trump, who was once a friend of Epstein’s, has denied he had any knowledge or involvement with the moneyman’s sex crimes. After initially promising to release the Justice Department files on the case, and announcing that a list of Epstein’s clients was “on her desk,” Pam Bondi, Trump’s attorney general, abruptly announced in July that a review of the files revealed there was no Epstein client list and no credible evidence that others were involved in his crimes.

That led to a public outcry, especially from Epstein’s survivors who held an emotional press conference on Capitol Hill in September to implore Trump to release the files. Trump has called recent attention to the case a hoax.

Key questions have long been asked about how Epstein was able to obtain federal immunity in the first place. A judge later ruled that the plea deal, which was initially sealed by Acosta’s office, was illegal because it was kept from Epstein’s victims and their attorneys.

The House Oversight Committee on Friday released the transcript of testimony by Menchel’s former boss, Alexander Acosta, who testified Sept. 19 in front of the committee. Acosta, Trump’s former labor secretary, testified that he and other federal prosecutors, including Menchel, didn’t want to take Epstein’s case to trial because they considered it a “crapshoot.”

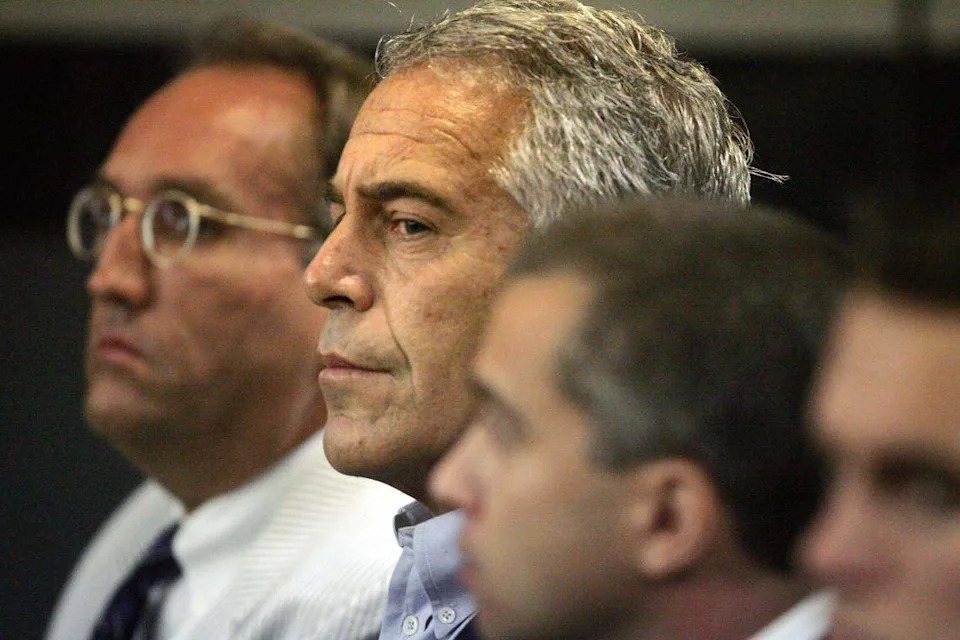

In this July 30, 2008 file photo, Jeffrey Epstein is shown in custody in West Palm Beach, Fla.

In its coverage of the case, the Herald raised questions about Menchel’s role in negotiating the deal. Besides Acosta and Menchel, the case was overseen by prosecutors Jeffrey Sloman, Andrew Lourie and Ann Marie Villafaña.

The Herald found that Villafaña, the lead line prosecutor, drafted an 82-page prosecution memo directed to Acosta, his deputy, Sloman, and Menchel, who was then head of the criminal division. In the memo, she proposed a 60-count indictment of Epstein on sex trafficking charges.

A subsequent probe by the Justice Department’s Office of Professional Responsibility (OPR) later found that its child exploitation division in Washington reviewed Villafana’s materials, offered to work with her and called the memo “exhaustive” and “well done.”

Acosta would later tell federal investigators he could not recall ever reading her memo, and that he relied on Menchel and others to know the details of the case. Acosta testified that he never met Epstein or his accomplice Ghislaine Maxwell, who is now serving a 20-year sentence for child sex trafficking and abuse. In his comments before the committee, Acosta also reiterated that he trusted Menchel, who proposed the plea deal with Epstein’s lawyers.

An OPR report issued in 2020 describes how Villafaña became angry in July 2007, when Menchel explained to her in an email that he had offered the deal to Epstein lawyer Lilly Sanchez, the only woman involved in Epstein’s defense. Villafaña felt it was an end-run around her, the report said.

The report also noted that Menchel had dated Sanchez, should have informed his bosses about it and probably should have been recused from the case.

Alex Acosta, right, speaks as President Donald Trump listens at the White House on September 17, 2018 in Washington, DC.

Acosta was asked about Menchel at least 17 times during his testimony before the House Oversight Committee. He indicated that he had not been aware that Menchel had a prior romantic relationship with one of Epstein’s lawyers and that Menchel should have told him so that they could have discussed whether there was a conflict of interest.

Acosta was also questioned about a photograph that allegedly showed Menchel skiing in Aspen with Epstein sometime in the early 2000s. The committee failed to produce the photograph when asked for more information by Acosta.

House Oversight Committee question for Alexander Acosta about a picture allegedly showing Jeffrey Epstein and Matthew Menchel skiing together.

Menchel left the US Attorney’s office in August 2007, before Epstein’s deal was finalized, to take a job with the international law firm Kobre & Kim. His LinkedIn profile indicates he is still a lead trial attorney at the firm.

Ultimately, Acosta approved Epstein’s plea deal in 2008 despite evidence that Epstein had molested dozens of high school girls whom he lured to his Palm Beach home to give him massages. The “massages” were a pretense to molest the girls, who ranged in age from 13 to 17 years of age.

Epstein pleaded guilty to two state prostitution charges, one involving a minor, and would serve only 13 months in a county jail. Although he was forced to register as a sex offender, he was allowed to leave the jail each day to go to his office in West Palm Beach. Several women later filed lawsuits that claimed they were sexually abused by Epstein in his office while he was supposed to be supervised by the Palm Beach Sheriff’s Office.

Acosta testified that Epstein’s defense team tried to get Epstein off the hook entirely, but he told lawmakers that he believed Epstein’s crimes warranted jail time and stood his ground. Still, he and the other prosecutors — including Villafaña — all agreed that taking it to trial would risk him escaping jail altogether, he said.

Part of the reason for the decision, Acosta said, was the reluctance of his underage victims to testify.

“Some refused to talk whatsoever,” Acosta said of the victims. “Others said he did nothing wrong and that’s the evidence you have, right?”

Still, public court records show that Palm Beach police and the FBI did gather other evidence — including phone records showing Epstein had contacted underage girls, physical evidence and photographs that the girls were in his home and phone message pads showing countless messages left for him about “girls” being available for “massages.”

Several victims also told the Herald that they were willing to cooperate with his prosecution. Many said they felt the prosecutors betrayed them.

Acosta said he wasn’t familiar with the corroborating evidence in the case and relied on his top prosecutors’ recommendations.

He explained to the committee that while the prosecutors believed a crime had been committed, he didn’t think jurors would understand that the nuances of the case — in other words, the jury would think the victims were prostitutes.

“I want to be crystal-crystal-clear, lest I be taken out of context or lest I be clipped on this: No one in our office ever thought that the victims were anything less than victims. No one thought that they were — you know, the idea that they were involved as anything other than victims — did not cross the mind of a soul,” he said.

Acosta admitted that Epstein’s lawyers — and their aggressive tactics — would also make the case hard to win at trial.

“We put him in jail, he registered as a sex offender, and the victims had an opportunity to recover. And that was a win,” Acosta told the committee. “Looking at all of this, the ultimate judgment was, ‘Do you roll the dice?’ and if he gets away with it, you’re sending a signal to the community that he can get away with it.”

Acosta was appointed by Trump as labor secretary in 2017. He resigned after Epstein’s 2019 arrest because, he said, he felt the scandal would be a distraction for the Trump administration.