When Ed McGinley heard in May that the wilderness preserve where he takes students was under threat of development, his first reaction was disbelief.

Just months earlier, McGinley joined the thousands of Floridians who protested against the state’s proposal to build a hotel on nearby Anastasia State Park. The sweeping bipartisan outcry caused the DeSantis administration to ultimately back down.

But just as that controversial plan died, another sprang up in his community: The state was now considering trading away 600 acres of the Guana River Wildlife Management Area in St. Johns County.

“We just did this with the state parks,” said McGinley, a professor of natural sciences at Flagler College, referring to mobilizing protests in defense of public lands.

“And now we’ve got to do it again.”

If 2024 was defined by a rare display of political unity against what many Floridians considered the most direct threat to their beloved public outdoor spaces in years, then 2025 was marked by a single question as more environmental threats emerged: How is this happening again?

From stories of controversial land deals to the emergence of an unpopular plan to drill for oil closer to Florida shores, it was a busy year for the Tampa Bay Times’ newly formed Environment Hub.

Here are some of the top environmental stories of the year.

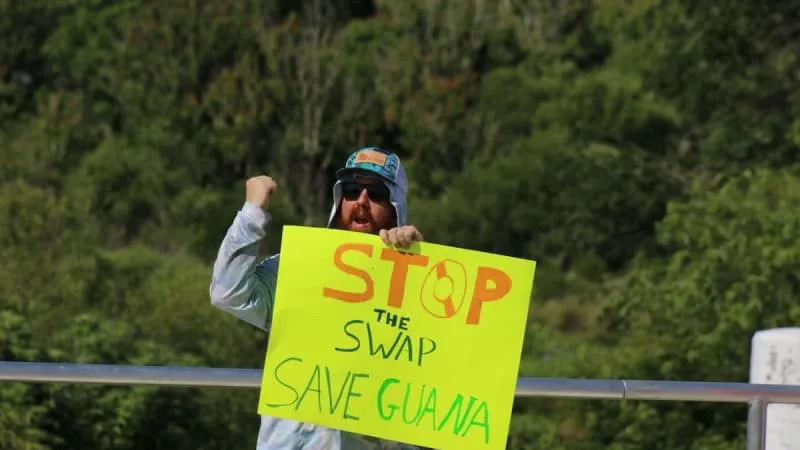

On a hot morning in May, hundreds of protesters gathered on the corner of A1A in St. Johns County to oppose the plan to swap away 600 acres of the Guana River conservation land, a bustling expanse of salt marshes and pine flatwoods.

The proposal emerged when a little-known committee within the Florida Department of Environmental Protection released an agenda for a previously unscheduled meeting. It showed a newly created private company, The Upland LLC, had asked the state for the preserved land — and the state was considering giving it away.

Opposition reached all the way to the White House: Susie Wiles, chief of staff for President Donald Trump and a longtime resident of northeast Florida, told the Times the plan was “outrageous and completely contrary to what our community desires.”

The developer ultimately withdrew the plan. And now, a Republican lawmaker in St. Augustine has filed a bill to increase transparency around state land deals.

Gov. Ron DeSantis signed a bill in May to prohibit the building of golf courses, hotels and other amenities on state parks, putting an end to a nearly yearlong controversy.

His signature was consequential in part because the bill directly outlawed an initiative his administration led last year: to develop nine state parks, including golf courses in Jonathan Dickinson State Park, pickleball in Pinellas County’s Honeymoon Island and a hotel near the coastal dunes of Anastasia State Park.

Sen. Gayle Harrell, a Republican from Stuart, sponsored the legislation. Her district is home to Jonathan Dickinson, the epicenter of the parks scandal, where scrub habitat could have been developed into golf greens.

“Without the support of the people of Florida, this would not have happened,” Harrell told the Times in May. “The people stood up and said, ‘Our parks are precious and they should be preserved.’ They are the ones who won this battle.”

The law required a report by December detailing the repairs needed across Florida’s 175 state parks. When it was released earlier this month, the report showed Florida’s state park system has a nearly $759 million backlog of repairs to maintain and enhance Floridians’ access to outdoor spaces.

The potential environmental and human rights concerns stemming from the quickly built immigrant detention center in Collier County, dubbed Alligator Alcatraz, dominated headlines in 2025.

The MiccosukeeTribe of Indians of Florida joined advocacy groups Center for Biological Diversity and the Friends of the Everglades, founded by environmental activist Marjory Stoneman Douglas in 1969, in a lengthy legal battle in an attempt to shut down the facility. They have argued in court that the state and federal government did not follow environmental regulations before the site was constructed in the heart of the Everglades.

In July, the Times explored the harm that the bright lights from the facility could have on Everglades wildlife that rely on the veil of nightfall to thrive, including the Florida bonneted bat and the Florida panther.

After a rigorous process with the U.S. National Park Service, DarkSky International in 2016 designated Florida’s Big Cypress National Preserve as the nation’s first preserve to achieve “dark sky” status, meaning it’s home to one of the last remaining reservoirs of darkness unimpeded by the glow of human development.

The group told the Times this summer that the artificial light from Alligator Alcatraz “directly threatens” the preserve’s renowned natural darkness and disrupts endangered nocturnal wildlife.

As of this month, the facility is still operational and housing detainees.

For the first time in a decade, a Florida black bear hunt returned to the Sunshine State.

After months of contentious public debate, Florida’s wildlife commissioners voted unanimously in August to approve a 23-day bear hunt that allowed for up to 172 bears to be killed. The commission also laid the groundwork for future bear hunting seasons.

Since the prospect of a new hunt first emerged, several key questions remained, including whether the state’s bear population is too high or too low, what methods should be allowed to hunt and whether the decision is being driven by sound science.

The hunt began Dec. 6 and runs through Dec. 28. As of mid-December, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission had not released any information about how many bears had been killed so far, despite requests from the Times and other media outlets.

Florida’s top leaders approved a fast-tracked deal in September to pay a campaign donor more than $83 million for his companies’ 4 acres of waterfront Destin land, disregarding concerns from conservationists and some Republican officials over the land’s price tag.

That deal closed earlier this month.

The now-former landowners, Pointe Mezzanine LLC and Pointe Resort LLC, are both registered in state corporate filings to Robert Guidry, a Louisiana business owner.

Records show Guidry, who was implicated in a bribery scandal involving former Louisiana Gov. Edwin Edwards in the early 1990s, and companies registered to him have donated more than $400,000 to state political committees, including one supporting DeSantis.

State environment officials have defended the purchase, sayingit will help expand public access to an adjacent city park and offer more recreational opportunities in a highly urbanized area.

But the Times interviewed more than a dozen conservation experts, including former top state environmental regulators who, combined, have worked under the administrations of five governors. They shared similar concerns about the Destin purchase, saying it raised unsettling questions about which landowners state leaders are prioritizing for conservation buys.

Lobbyist wrote proposal directing Florida to buy pricey 4 acres in Destin

The amount of money spent on the property could have been used to add hundreds of acres of land for vital panther habitat in the Florida Wildlife Corridor, they said.

“There’s a lot of environmentally sensitive lands on the state’s list that could’ve used this money,” Colleen Castille, who served as the head of Florida’s Department of Environmental Protection under former Gov. Jeb Bush from2004 until 2007, told the Times in October.

The Trump administration released new plans in November that could push offshore oil drilling closer to Florida shores.

The plan calls for opening a swath of the eastern Gulf of Mexico that has been traditionally off-limits to new drilling. The federal government would auction two drilling leases in that region beginning in 2029, according to the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management.

In a rare display of unity, all 28 of Florida’s U.S. House members and both U.S. senators signed a bipartisan letter earlier this month urging President DonaldTrump to keep offshore oil drilling away from the state’s coastline.

The letter was significant in that it merges long-standing Republican and Democratic philosophies against Florida offshore drilling — that it could thwart Florida’s offshore military testing operations while also harming the state’s coastal economy dependent on healthy, biodiverse beaches — into a lockstep call for a course reversal.

“We urge you to uphold your existing moratorium and keep Florida’s coasts off the table for oil and gas leasing,” the lawmakers wrote. “Florida’s economy, environment, and military readiness depend on this commitment.”

The delegation reminded Trump of the devastation caused by the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill: It wiped billions of dollars from a now-annual $127 billion tourism industry that employs more than 2 million people.

As Florida offshore drilling looms, birds less protected from spills under Trump

It also caused “irreparable damage” to beach ecosystems and coastal communities, they said.

The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management is accepting public comments on the drilling proposal until Jan. 23.

The Times’ investigative team has spent the year reporting on a pervasive issue upending ecosystems and human health across Florida: water pollution.

Part 1 of the “Wasting Away” series, published in April, explored how rampant pollution caused manatees to starve in a 2021 die-off in the Indian River Lagoon on the Atlantic Coast. Florida’s biggest sources of water pollution — agriculture and development — aren’t held to strict limits on the nitrogen and phosphorus that flow off farms and urban streets, the investigation found.

The second part, published in October, put big-time polluting industries under the microscope and underscored the largely failing efforts of state government to rein in their damaging ways.

“Florida officials ask developers, farmers and ranchers to reduce nitrogen and phosphorus contamination by using methods recommended by the state. In return, regulators assume that the companies aren’t harming the environment. No one bothers to check,” the report found.

Another story, published this month, focuses on human health and explores how chemicals pollute drinking water wells and fuel harmful algae blooms that can make people sick.

Florida Power & Light, the largest electric utility in the nation, asked for the biggest rate hike in American history in early 2025 — with a rate of shareholder profit that would have been the highest in the country.

Consumer advocates, including the public counsel appointed by the Legislature, went to war.

The company’s chief executive had to take the witness stand in Tallahassee, and people with financial ties to the company praised the rate hikes in public hearings.

Regulators approved a deal to end the case, despite protests from the public counsel. But the fight could end up in the Florida Supreme Court.

One year after Hurricanes Helene and Milton walloped the Tampa Bay area, how is the region recovering?

Our environment team explored that question in September. What we found: While Tampa Bay has largely healed, recovery is still a slog in the areas hit hardest. It has been hindered not only by cost but also by slow permitting, battles over substantial damage reports and contracting woes.

By the numbers:

After record storm surge and river flooding, at least 10,000 Tampa Bay homeowners received letters informing them their home could be “substantially damaged,” meaning the cost of repairs would exceed half the home’s total value. They would need to bring the property up to more stringent storm standards or demolish it altogether.

Pinellas post-hurricane home assessments rife with flaws

Pinellas County has issued about 5,000 building permits related to hurricanes Helene and Milton to homeowners in unincorporated parts of the county. In flooded neighborhoods, home prices dropped 40%.

The Times continues to report on continued recovery efforts.

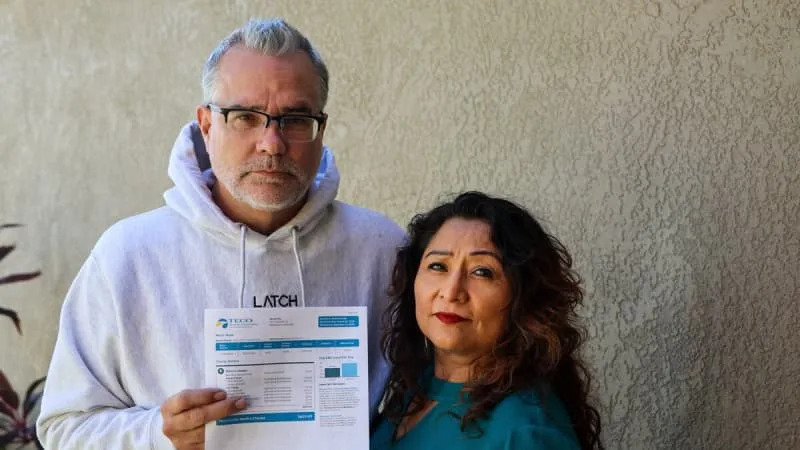

Steep storm recovery costs from the destructive 2024 hurricane season combined with base rate hikes and an oppressively hot summer to make 2025’s electric bills soar.

Many residents told the Times that their bills were higher this year than ever before.

The Times dug into the reasons behind the high costs and how they affected residents in an ongoing series of stories about energy affordability called “Power Struggle.”

A month after Floridians first learned a long-celebrated campground could be closed and sold, state water managers approved an agreement in September ensuring it stays open and in public hands.

Weeks of public unease over the fate of the beloved Chassahowitzka River Campground ended when the Southwest Florida Water Management District board voted unanimously to approve a deal with Citrus County to keep the campground publicly owned and accessible for the next four decades.

The 40-acre campground sits adjacent to the winding, spring-fed Chassahowitzka River, a sanctuary for manatees, otters, rays, sharks, alligators and myriad other species.

The decision came about an hour and a half into the district’s September governing board meeting.

“At a time when public lands across Florida are facing increasing pressure, this agreement is a shining example of what we can achieve when communities, agencies, and conservationists work together to keep these special places in public hands,” Casey Darling Kniffin, the conservation policy director for the nonprofit Florida Wildlife Federation, said at the time.