Along a 36-mile stretch from Cocoa through verdant east Orange County, Brightline trains reach 125 miles per hour on their trek to Orlando International Airport, among the top speeds for any U.S. train line.

Yet this new stretch for the privately-run railroad, long known as the nation’s most dangerous passenger train, has an even more important distinction: In 27 months since opening, its breakneck pace has not led to a single fatal accident.

This northernmost portion boasts critical safety features missing elsewhere along the 233-mile, Miami-to-Orlando trek. It is shielded from its surroundings by six-foot-high chain link fence and never crosses a road at grade.

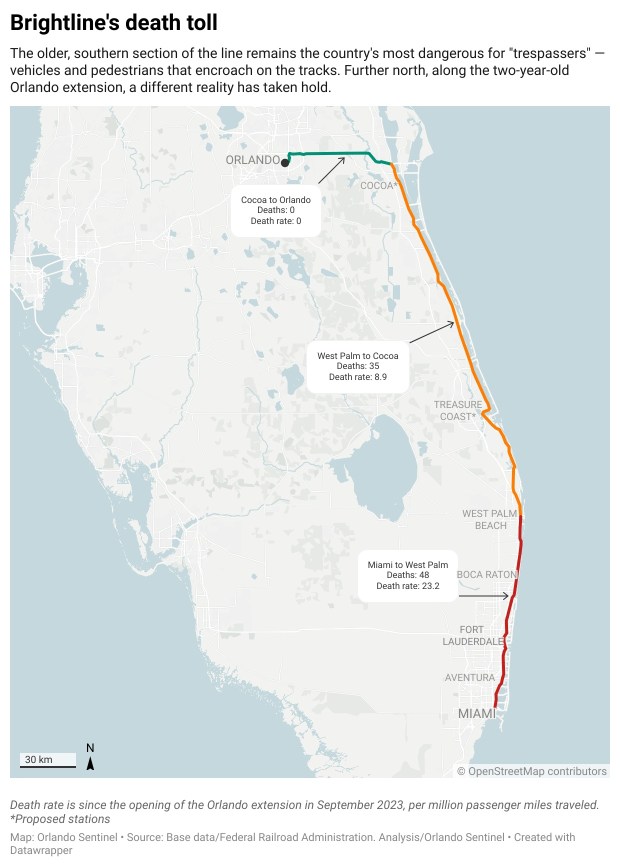

Those factors are helping to recast Brightline’s dubious record of 186 “trespasser” deaths in its eight years of operation, most of which came on the older portion of the track from West Palm Beach south, where locomotives vie with cars and pedestrians as they race through lightly-protected city streets.

In fact, an Orlando Sentinel analysis has found, in the last two years Brightline has ceded the deadliest train title, as measured by death rate per million miles traveled, to California’s San Diego-to-LA Coaster line. Brightline’s rate has plummeted from 36 in the years before the extension opened to 11 over the last two years and 19 since its inception, mostly because the safer new track has pulled down its overall average.

The Sentinel’s analysis offers powerful lessons for the future of Brightline, which hopes to take its service to Tampa with an extension that — like the spur from Cocoa to Orlando — it would construct from scratch.

Yet the line remains plagued by the dangerous nature of the track from Miami to West Palm, built along the existing Florida East Coast Railway with only intermittent stretches of fencing and nearly 200 at-grade crossings. Improvements to that section have been hamstrung by formidable costs, community resistance and — critics say — Brightline’s own reluctance to commit to safety.

One such critic is Mike Arias, a retired transportation officer who worked four decades for Miami-Dade Fire Rescue. Arias accuses Brightline officials of deferring or ignoring needed safety improvements at what he calls the “sacrificial expense” of the slain and wounded.

“I don’t know how these individuals that are responsible for this, how they can even sleep at night for heaven’s sake,” he said. “When you have lost lives that could have possibly been prevented.”

Brightline faces a crossroads if it is to succeed in efforts to transform its money-losing operation into a viable business. The prospect of punishing delays on the accident-prone sections of the route — every accident shuts down the line for hours — can turn off potential riders, even Central Floridians whose southward journey, a quick 3 1/2 hours to Miami in the best circumstances, inevitably proceeds from an accident-free to accident-prone zone.

Brightline faces a crossroads if it is to succeed in efforts to transform its money-losing operation into a viable business. The prospect of punishing delays on the accident-prone sections of the route — every accident shuts down the line for hours — can turn off potential riders, even Central Floridians whose southward journey, a quick 3 1/2 hours to Miami in the best circumstances, inevitably proceeds from an accident-free to accident-prone zone.

Clearly, Brightline can build and operate a safer railroad. But will it?

From bad to better

Brightline’s 67-mile stretch out of Miami was a kill zone from its 2018 opening – as it suffered from design compromises made to send a high-speed train through a heavily populated area in an existing right-of-way, and a series of decisions to contain costs.

Few high speed rail lines anywhere in the world cross so many streets at grade. Federal regulations limited the trains to 79 mph on the initial route because of the crossings, but there’s little indication that mitigated the danger.

Local communities made the safety issue worse with their insistence on quiet zones in many sections, which prohibit trains from sounding their horns.

By late 2019, an Associated Press analysis declared Brightline had “the worst per-mile death rate of the nation’s 821 railroads” — the 41 fatal strikes tallied by then had begun during initial testing in 2017. The company promised new fencing, safer crossing gates and suicide prevention programs, with its president saying Brightline would like nothing better than for the death rate to go to zero.

But improvements were slow in coming, and the death rate edged up rather than dipping. At the end of 2019, it was 34.9 per million miles traveled; by mid 2023 it was 35.6, with total fatalities reaching 107.

Broward Sheriff’s Deputies and Pompano Beach Fire Rescue work the scene of a fatal accident on North Dixie Highway in Pompano Beach, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2019. Though dramatic, vehicle collisions cause just a fraction of Brightline fatalities. Pedestrians, however, are at great risk. (Joe Cavaretta/South Florida Sun Sentinel file)

Broward Sheriff’s Deputies and Pompano Beach Fire Rescue work the scene of a fatal accident on North Dixie Highway in Pompano Beach, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2019. Though dramatic, vehicle collisions cause just a fraction of Brightline fatalities. Pedestrians, however, are at great risk. (Joe Cavaretta/South Florida Sun Sentinel file)

Then the new, 166-mile extension from West Palm Beach to Orlando opened, and a different Brightline emerged. Or at least, part of it was different.

Today’s Brightline can be considered as three distinct segments – the 67 miles from Miami to West Palm, with 174 at-grade crossings, little fencing and a 79-mph top speed; West Palm to north Cocoa at the FL 528 turnoff, 130 miles with 157 street level crossings where more secure gate arms and medians allow speeds up to 110 mph; and Cocoa to Orlando, 36 fully fenced miles of track with no at-grade crossings where trains may reach 125 mph.

The West Palm-to-Cocoa section, while new, mostly lacks fencing and has a relatively high tally of fatalities at 35 from its fall 2023 opening through September of this year. Passing through Brevard County, Brightline has recorded 16 deaths, a mixture of pedestrian and vehicle strikes, accidents and suicides.

One of the saddest incidents occurred on Christmas Eve of 2023, when a woman suffering from alcohol and drug problems walked in front of a train in Melbourne. Katherine Stimus, who reportedly was also mother to an autistic child, had left a letter absolving that child of responsibility but saying “I’m ready to rest.”

But overall, Brightline’s fatality story has a revised narrative.

The line’s death rate over its first six years was shockingly high – 2 ½ times the rate of second-place Coaster, at 14.5, and more than ten times the calculation for two well-traveled urban lines that cut through heavily populated areas, New Jersey Transit and the Long Island Railroad, both of which averaged about 2.5 deaths per million miles from 2018 to 2025.

Brightline tallied 48 fatalities in 2024, its highest year ever, and 24 through September of 2025, but making longer runs with more trains per day, it is logging eight times as many total passenger miles in recent months as it did in its first full year of operation. As a result, the relative level of fatalities has plunged.

The death rate of 11.3 since the new line opened includes 21.8 from the West Palm Beach station south, and 7.0 to the north. If the segments were compared separately to other lines, the northern section would be the ninth most dangerous railroad in the country, while the southern piece would rank number one.

“Safety is the top priority at Brightline,” the company said in a statement in response to the Sentinel analysis. “We have been a leader in the industry on safety initiatives related to education, enforcement, and engineering. As a result of our focus, including our significant investments in safety infrastructure, the numbers are trending in a more positive direction. Incidents in 2025 are nearly 17% below the previous year and April was an incident-free month. However, there is always more to do.”

Although the numbers are relatively better, the tragedy continues. The Sentinel reviewed available police reports for Brightline incidents since the Orlando extension to gain insights into the current situation.

A heartwrenching case involved Gary Millar, a Spanish-language interpreter at the imposing Palm Beach County Courthouse, who was killed in December 2023 after walking about 90 yards to the nearby tracks at the beginning of his lunch break.

Coworkers said Millar, 69, had recently shown signs of hearing issues as he interpreted inside the courtroom.

Millar and another man were approaching the train crossing at 3rd Street when the bells and lights started up and the crossing arm came down. Millar started to run across the tracks as the other man yelled out, but the train barreled into him.

A former colleague of Millar’s at another courthouse wrote in an obituary that he “never heard him utter a rash word against anyone. . . He embodied kindness even under challenging circumstances.”

A police report said his death appeared to be an accident.

The nature of trespassing deaths

The contrast between Millar’s death and Stimus’ passing captures the twin phenomena fueling the Brightline carnage: accidents and suicides. The rail company has been clear that neither type of mishap is its fault, so much so that some critics have accused it of victim blaming.

Broward Sheriff’s officials on the scene where a pedestrian was killed by a Brightline train along Southwest Third Street and Dixie Highway in Pompano Beach on Jan. 1, 2020. Without fencing in stretches like this one, pedestrians find it easy to tempt fate – accidentally or deliberately. (Carline Jean/South Florida Sun Sentinel file)

Broward Sheriff’s officials on the scene where a pedestrian was killed by a Brightline train along Southwest Third Street and Dixie Highway in Pompano Beach on Jan. 1, 2020. Without fencing in stretches like this one, pedestrians find it easy to tempt fate – accidentally or deliberately. (Carline Jean/South Florida Sun Sentinel file)

In a July statement, Brightline’s vice president of operations, Michael Lefevre, summed up the company’s stance, which it has expressed from the beginning of service.

“These incidents are tragic and avoidable. More than half have been confirmed or suspected suicide – intentional acts of self-harm,” he said. “All have been the result of illegal, deliberate and oftentimes reckless behavior by people putting themselves in harm’s way.”

The company has not been judged at fault for any of the deaths on its tracks, the Federal Railroad Administration said last week, a finding that would occur if operator error or maintenance issues contributed to a fatality.

Todd Baker, a Boca Raton personal injury attorney who represents several people who lost loved ones to Brightline incidents, accused the company of anti-victim rhetoric that left his clients “mortified.”

“[It’s] adding insult to injury,” Baker said. “I mean, people make mistakes every day, but they go home. They make it home.”

The Sentinel found a lower proportion of suicides than Brightline’s “more than half” assertion. Of 60 fatality incident reports reviewed, 25 were confirmed or suspected suicides, about 42 percent. All but one of those involved pedestrians.

Though lower than Brightline’s claims, the suicide percentage calculated by the Sentinel is still much higher than that tallied by the Federal Railroad Administration, at 20 percent since service began. But FRA lists a fatality as a suicide only if a medical examiner or coroner rules it as such, so its data clearly understates reality.

Federal data on pedestrian versus vehicle accidents is more reliable. Just under 10 percent of all Brightline fatalities since service began, 19 in total, have involved vehicles encroaching on the tracks, according to FRA. An estimated 167 have involved pedestrians.

Vehicles wait at a rail crossing at Viera Boulevard and U.S. 1 in Brevard County on Thursday Sept. 21, 2023, the day before Brightline’s northern segment began operations. While trains are limited to 79 mph further south, they may travel up to 110 mph in this section because of the more extensive safety equipment in place. (Kathy Laskowski/South Florida Sun Sentinel)

Vehicles wait at a rail crossing at Viera Boulevard and U.S. 1 in Brevard County on Thursday Sept. 21, 2023, the day before Brightline’s northern segment began operations. While trains are limited to 79 mph further south, they may travel up to 110 mph in this section because of the more extensive safety equipment in place. (Kathy Laskowski/South Florida Sun Sentinel)

The Sentinel’s review makes clear the level of despair that drives some people to walk into the path of a train.

Brett Tucker, 56, who died on the tracks in September 2024 in Delray Beach, had threatened suicide multiple times and been involuntarily committed to detention at least twice. Cheryl Townsend, who trespassed between crossings in Rockledge in May 2024, suffered from bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Witnesses said she looked at the train but didn’t move as it approached.

Winter Springs resident David Townsend, Cheryl’s ex-husband, described her as a loving mother to their young daughter. He said he tries to keep the girl’s memory of Cheryl alive.

“I show her pictures, quite a bit, of her and her mom,” he said. “It’s just to keep her on her mind, especially over the holidays and things.”

Experts who study rail safety say that suicide prevention programs can help mitigate these problems. While Brightline has made some efforts, the country’s leader in such programs is considered to be Caltrain in the San Francisco Bay Area, where suicide incidents regularly lead to public outcry.

In the last few decades, Caltrain has provided extensive suicide prevention signage; partnered with local and national nonprofits to offer suicide counseling, including through text message services; deployed security guards and volunteers to watch the tracks; and pioneered camera monitoring approaches.

But even Caltrain’s consistent efforts have failed to keep its fatality numbers consistently low – after falling to a low of two in 2010, deaths shot back up to 20 in 2015, for example – though its death rate has always been lower than Brightline’s.

That’s part of the reason why the Bay Area railroad is now involved in a concerted and costly effort to get rid of its street-level crossings.

“Working with the cities that we serve in order to build grade separations wherever possible, so you can eliminate crossings, that’s the safest option,” said Dan Lieberman, Caltrain’s public information officer.

Others favor fences.

Dr. Angela Clapperton is a senior research fellow at the University of Melbourne in Australia who studies suicide prevention. She was part of a study that looked at the effectiveness of installing trackside fencing in preventing suicides on a rail network in Victoria, Australia.

Clapperton said fencing was installed at 36 locations to restrict access to the tracks at known problem areas. While her team found no overall reduction in suicides when considering all fenced sites together, it did find a 57% reduction in suicides within 1000 meters of sites where the fencing was 100 meters or longer.

“We concluded that for fencing to be an effective suicide prevention measure on rail networks, authorities should prioritize installing longer continuous runs rather than short fragmented sections,” she said. “Completely restricting access appears key to reducing suicides on the railway.”

Clapperton said many suicides are impulsive and interventions such as fences and barriers are thought to work, in part, by creating critical time for the impulses to pass and allowing the opportunity for others to intervene.

But there’s a clear challenge in installing fencing and other safety measures, in particular for a private company like Brightline: It adds a lot of expense to running a train line. The most secure, hardened fencing can cost a half-million dollars a mile.

What can be done?

In 2014, a federal transportation engineer sounded the alarm about planning for All Aboard Florida, complaining the high-speed rail effort that would become known as Brightline was not “exercising appropriate safety practices and reasonable care” in its design.

Project officials, wrote Frank Frey, regarded federal safety principles as “guidelines, not regulations” in resisting alternatives for crossing gates and vehicle detection systems that would have meant “an additional financial burden of $47 million” for the operation, which hoped — and still aspires — to operate at a profit.

Eleven years later, the debate continues over whether Brightline has done enough to operate the Miami-to-Cocoa portion of its line safely.

A Brightline train collided with a fire truck at East Atlantic Avenue and Southeast First Avenue in downtown Delray Beach on Saturday afternoon, Dec. 28, 2024. After long delays, Brightline is converting more intersections to “sealed crossings” that prevent most vehicles from encroaching on occupied tracks. (Mike Stocker/South Florida Sun Sentinel file)

A Brightline train collided with a fire truck at East Atlantic Avenue and Southeast First Avenue in downtown Delray Beach on Saturday afternoon, Dec. 28, 2024. After long delays, Brightline is converting more intersections to “sealed crossings” that prevent most vehicles from encroaching on occupied tracks. (Mike Stocker/South Florida Sun Sentinel file)

The company has opposed efforts to tighten state and federal oversight and mandate certain safety measures like building and maintaining fencing along the tracks at Brightline expense. Even today, Brightline has declined in response to inquiries from the Orlando Sentinel and others to say how many miles of fence are in place on the southern portion of the line.

The company says, however, that it has spent more than $600 million for corridor upgrades and crossing improvements, and notes that it fully complies with all state and federal safety guidelines.

Arias, the former Miami-Dade Fire Rescue transportation officer turned safety advocate, believes Brightline should spend more for safety.

He pointed to a recent lawsuit where a British court ordered Brightline to pay $115 million to billionaire Richard Branson’s Virgin Group after Brightline cancelled a branding deal with the company.

“That money, their own money, should have been used, okay, to perform all of the essential safety enhancements that have been much needed along the pathway,” he said. “Maybe it wouldn’t have covered it all, but it would certainly have covered a grand portion of it.”

Brightline is not alone in its reluctance to spend.

Consider the $25 million federal grant for Brightline safety improvements announced by the Biden administration in August of 2022. It aimed to add 35 miles of fencing in short stretches, including many where foot paths show tracks are routinely traversed, and make improvements to 327 at-grade crossings to keep vehicles from darting around lowered arms.

The most urgent issue: An estimated 103 crossings on the old portion of the line still have two gate arms, a setup which is relatively easy to evade.

While it may seem unthinkable, some of Brightline’s most notorious accidents have come from such unwise driving, including the December 2024 collision involving firefighter David Wyatt in Delray Beach. Wyatt proceeded around gate arms after seeing a freight train pass by and neglected to notice a Brightline train speeding from the south.

“We want Brightline to be in the news for all of the right reasons,” Democratic Congresswoman Debbie Wasserman Schultz had said two years earlier, at a news conference celebrating the Biden administration funding.

But the money wasn’t ultimately “released” until mid-2025, under the Trump administration. The full project, now set for $66 million including $10 million from Brightline, will be underway next year.

“Their failure to execute on these rail grants — some of which stretch back years — put Brightline’s three million annual passengers and Florida communities in unnecessary danger,” U.S. Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy said in September.

The new effort will also include development of an AI-backed monitoring system, Wi-Tronix, to collect real-time data of trespass activity along tracks and telegraph potential collisions to train operators, according to a 2023 Brightline news release. Brightline said the system would be the first of its kind.

Cars cross railroad tracks on Sunrise Blvd. near Federal Hwy. in Fort Lauderdale on Wednesday, Oct. 22, 2025. Transportation planners are studying the possibility of building tunnels under the tracks at five major railroad crossings in Fort Lauderdale, but the expense would be huge. (Amy Beth Bennett / South Florida Sun Sentinel)

Cars cross railroad tracks on Sunrise Blvd. near Federal Hwy. in Fort Lauderdale on Wednesday, Oct. 22, 2025. Transportation planners are studying the possibility of building tunnels under the tracks at five major railroad crossings in Fort Lauderdale, but the expense would be huge. (Amy Beth Bennett / South Florida Sun Sentinel)

Another pain point has been the insistence of local communities in South Florida on “quiet zones” along the tracks, where trains are mostly prohibited from blowing their horns to sound a warning for vehicles and pedestrians. Part of the effort to build community support for the train’s construction, those zones now draw heavy criticism from advocates who say they compromise safety.

Susan Mehiel, the leader of the Alliance for Safe Trains group based in Indian River County, cringes at the number of quiet zones in heavily populated, highly exposed areas.

“There are a number of places where there’s youth activity centers near train tracks, and there’s paths worn where the kids cross the tracks to get from their home to the center, or what have you,” she said. “I can see at nighttime, when there’s no bells and whistles, it’s just going to be disaster.”

A recent study by the Miami Herald and WLRN concluded that 53 percent of all Brightline crossings are in quiet zones, far higher than five comparable lines studied. For the San Francisco Bay Area’s Caltrain, the figure is 1 percent.

The Federal Railroad Administration says 51 Brightline fatalities — nearly 30 percent — have occurred in quiet zones. The safety concern is so great that Martin County Commissioners earlier this year decided not to enact quiet zones across that county’s 27 crossings, so that train horns could continue to blare.

But is the ultimate fix for Brightline — making the full length of its tracks more like the Cocoa-to-Orlando extension — attainable?

Dr. Ian Savage, a professor of economics at Northwestern University who researches transportation safety, notes that Florida’s urban landscape was never hospitable to passenger train safety.

Brightline West, the company’s second major rail project running from Las Vegas to Southern California, is being built like its most recent Florida tracks — from scratch, with a design that includes no at-grade crossings. In South Florida, the presence of the Florida East Coast Railway offered a financially attractive option to operate a high-speed line serving eager riders, but not the safest option.

Savage doubts a major overhaul with retrofitted, grade-separated crossings could ever happen here.

“Think of the property condemnation you would need and the disruptions to neighborhoods,” he said. “I mean [not only] the expense in just dollars, but I mean, what would it do to the urban environment?”

Others argue a better railroad is simply a matter of will.

“It is difficult to put these projects together…in terms of politics, in terms of the funding,” said Lieberman, the Bay Area’s Caltrain spokesperson, which despite the difficulty is trying to completely revamp an existing line. “It takes effort.”