The four houses were relocated from Johnson Street in 1990 when the MetroTech campus was built. They were selected by the LPC as well-preserved examples of the middle-class neighborhood that flourished there from the 1840s through the 20th century.

Photo: Landmarks Preservation Commission

For the past 35 years, a row of four vacant 19th-century townhouses on Duffield Street in Downtown Brooklyn has drawn curious looks from passerby. It’s rare to see empty houses, and a row of them at that, sitting vacant in a part of town defined by construction cranes and tall towers. They seem like the kind of thing that must have always been there, but in fact the houses were relocated from Johnson Street, three blocks away, to 182-188 Duffield in 1990, after the Landmarks Preservation Commission selected them to be saved as representatives of the historic middle-class enclave being razed to build the MetroTech campus. In exchange for the 16 acres that developer Forest City Ratner needed for the campus and office park, it agreed to move, preserve, and use the historic houses for “institutional, commercial, or residential purposes in keeping with their architectural significance.”

A rendering of the cross section of one of the townhouses, as used as a lobby for the new tower. The steps have been removed, doors replaced, and floors taken out to create a double-height lounge on the second and third floors.

Photo: Landmarks Preservation Commission

Instead, they’ve largely gone to seed. The dilapidated wooden trim and sagging porticos were spruced up a few years ago after preservationists complained to the Landmarks Preservation Commission, but the upstairs windows reveal glimpses of peeling paint, crumbling plaster, and collapsing ceilings inside. Neither Forest City Ratner nor Brookfield Asset Management, which took over MetroTech from Forest City in 2018, ever found a use for the houses, and Brookfield offloaded the houses a couple years ago.

Now the new developer, Watermark Capital, finally has a plan to put them to use: It’s proposing to refashion them into a glorified lobby for the 99-unit mixed-use tower it’s trying to build in the backyard. “They’re basically planning to demolish the rear sides of the townhouses, open them up, and graft them onto the tower,” Frampton Tolbert, the executive director of the Historic Districts Council told me. “The houses would just be a façade, almost like a folly.”

The exterior rear walls of the houses would become part of a tenant lounge/lobby.

Photo: Landmarks Preservation Commission

When Watermark paid $10 million for houses in 2023, it may have seemed like a deal (a real-estate listing touted the site as “heavily discounted,” with 100,000 buildable square feet, perfect for a “developer with landmarks experience”), but the site was widely considered to be undevelopable. It was, in fact, designed to be that way. Each house is individually landmarked, meaning they can’t be altered or demolished without the permission of the LPC, and the only possible place to build would be the backyards, which is only about 30 feet deep. There’s a narrow clearance on either side of the row roughly wide enough to drag a trash can through. The houses are bounded at the rear by the BellTel lofts, a landmarked Art Deco office building that was converted to condos in 2008, meaning that any project there would essentially be wedged up against other buildings on all four sides. It seems unlikely, several people told me, that you could get excavation and construction equipment into the backyard without dismantling one or more of the houses. (There are concerns, too, that the houses might accidentally — or accidentally on purpose — be destabilized and need to be torn down, a not-infrequent occurrence with landmarked buildings in the city.) There really is no way to build a large development on the site unless you do something crazy.

And Watermark’s plan, which was rejected by the local community board in the spring and is going before the LPC on Tuesday, is basically that. Renderings submitted with the application show some cosmetic changes to the townhouse façades, including a stoop removed for ADA compliance, new (seemingly code-compliant) double glass doors, and fireproof concrete siding in lieu of wood. But it’s when you go inside that it starts to look like a theme park: Floors are removed in every house — renderings show residents sitting on their laptops with the old house exteriors forming a kind of multistory lounge wall. “The houses were to be protected in perpetuity — there’s no expiration on the memorandum — but if you look at the plans, they would essentially be destroyed by this project,” says Jeremy Woodoff, a longtime employee of the LPC and the Department of Design and Construction, was at the LPC at the time MetroTech was being built and worked on the effort to select and relocate the houses. Watermark’s LPC application, he added, was unusual in that it has two alternate proposals on the bottom, suggesting they may be hoping to trick the commission into accepting a slightly less extreme plan as a win-win. Watermark, a somewhat prolific developer in the borough, could not be reached for comment: No one answers the phone at the office, the voicemail boxes are full, email addresses bounce back, and a contact form on its website went unanswered.

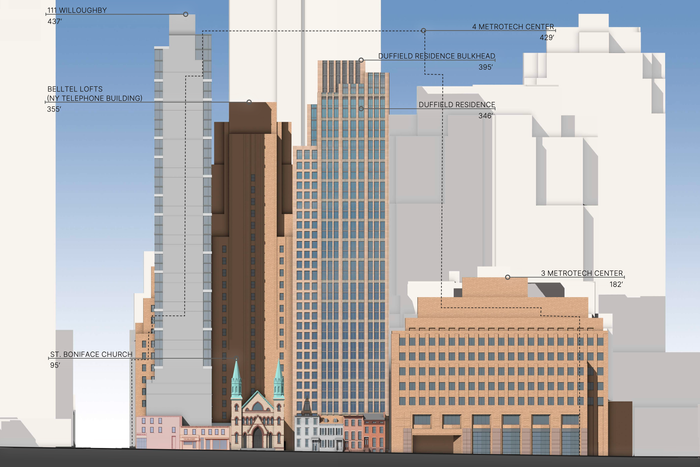

A rendering of what the 33 tower would look like. The building would be surrounded on all four sides, sandwiched between the church and a ten-story MetroTech building, with the rowhouses in front and BellTel lofts in the back.

Photo: Landmarks Preservation Commission

William Vinicombe, who lives in a house on Gold Street a few blocks away that has been in his family for over 100 years and was on the community board when it worked out the deal in the late 1980s, says that turning a row of historic houses into a façade for a tower jammed into their backyards feels like a betrayal of the agreement that was made with the community. “I was here the day they moved them,” he told me when we met in front of the houses on a recent afternoon. Downtown Brooklyn was hurting in the 1980s, he added, but it wasn’t abandoned or dead. People had been living in the houses before they were moved, people who had to be relocated and then lost the generational wealth that was in the properties. At the time, the community board thought the houses might be used for a museum or something else for the public. But the agreement didn’t stop them from being used as offices, rented out as residences, or sold off as homes, which certainly would have made sense as townhouse prices in the surrounding neighborhoods started to surpass $5 million. There were a lot of things that could have been done besides leaving the houses to rot, then claiming, as a campaign seemingly put together by the developer does, that the only way to restore these “treasured landmarks” is by turning them into the entrance lounge of a 33-story building.

In retrospect, the houses should have been protected from redevelopment with a deed covenant, which could have precluded new development on the site. But at the time, landmarking seemed sufficient. And maybe it will be. The LPC typically rejects façadism, Tolbert noted, although it’s not clear if the LPC will view this as a gut renovation with some exterior alterations — the kind of thing that would involve only back-and-forths over visible exterior portions — or something more substantial. But the new tower itself is certainly substantial, 33 floors looming over the three-story townhouses and the four-story church next door.

Another rendering of the lobby interior, incorporating the exterior back walls of the houses.

Photo: Landmarks Preservation Commission

And in a neighborhood that’s been more or less entirely redeveloped, whose most characteristic feature is its charmlessness, you can hardly accuse Duffield Street’s defenders of NIMBY-ism. They’re just trying to preserve the few designated landmarks they have. “It was the original part of Brooklyn that everything else grew from, but there’s so little left, it’s just bits and pieces,” says Christopher Young, who’s lived in the neighborhood for 16 years. On one side of the Duffield Street houses there’s a historic Catholic church that’s not landmarked, and about a block away is the Abolitionist House, at 227 Duffield, which was finally landmarked in 2021 after a 17-year battle set off by the Bloomberg Administration’s attempts to demolish it and five other houses for a park, now named Abolitionist Plaza (the city determined that there wasn’t sufficient evidence to save the other houses, though owners and a number historians believed they were also involved with the Underground Railroad and the abolitionist movement). It may not be a historic district like you’d find in Brooklyn Heights or Cobble Hill, but it’s a little cluster that offers a sense of the neighborhood that was there before. Young, Vinicombe, and Beth Eisgrau-Heller are trying to form a neighborhood association to make those bits and pieces more coherent, and, they hope, make the neighborhood feel less like a collection of luxury rental towers close to the subway. Eisgrau-Heller told me she’d love to see the houses become something akin to the Tenement Museum.

“It’s just an abject failure of imagination,” says Raul Rothblatt, who leads historic walking tours of the neighborhood and was involved in the effort to landmark the abolitionist house down the block. (He’s now a co-founder of the Friends of Abolitionist Place nonprofit.) “These buildings could be a tremendous resource to the neighborhood. And instead they’re treated like less than nothing.”

The backs of the rowhouses currently. The backyard is about 30 feet deep — the houses were situated on the site with traditional townhouse setbacks and standard-size backyards behind, with BellTel Lofts rising up at the rear.

Photo: Landmarks Preservation Commission

Sign Up for the Curbed Newsletter

A daily mix of stories about cities, city life, and our always evolving neighborhoods and skylines.

Vox Media, LLC Terms and Privacy Notice

Related