Democratic mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani’s promise of a four-year rent freeze for the city’s nearly 1 million regulated apartments is designed to make New York affordable for the people who live in them.

But, real estate experts warn, it will make the city more expensive for the New Yorkers occupying the 1.1 million market rate units, who are the people who have borne the biggest burden of skyrocketing rents over the past four years. While overall those people have more income to pay higher rents, they too are being priced out of the market.

“Freezing rent for stabilized units means that market-rate units will face higher annual increases, driven by a tight supply and landlords shifting higher costs such as soaring prices for insurance and taxes to open-market units,” said Jonathan Miller, CEO of Miller Samuel, a real estate consulting firm.

Insurance outlays increased by 19% in this year’s annual landlord operating cost price index compiled by the Rent Guidelines Board, which determines rent hikes.

The impact will be especially clear in the buildings that include both regulated and market-rate apartments, where tenants in rent-regulated apartments will likely be saddled with paying for all the cost increases in the building.

In the last four years, according to the September Elliman Report overseen by Miller, the median rent for new leases in Manhattan has jumped 36% to $4,450. In Brooklyn, it surged 37%, to $3,925.

The increases in rents for newly leased units are twice the rate of inflation, which totaled 18% during those years.

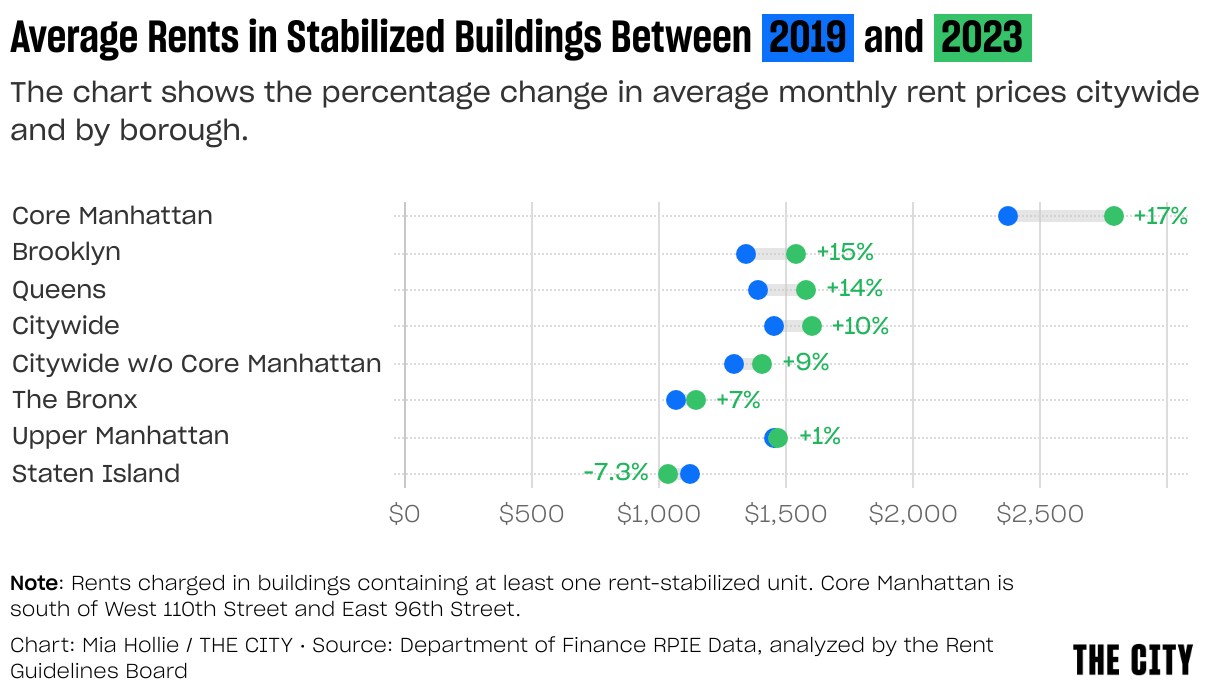

But the average rent in a building that contains regulated apartments has risen far more slowly, with the rent laws protecting longtime tenants and incentivizing them to remain in place. In the most recent four-year period tracked by the Rent Guidelines Board, ending in 2023, it rose only 7.5%, to $1,559. The board has since allowed a 2.75% increase on one-year leases last year and another 3% that went into effect Oct. 1 — but only on the regulated apartments.

Most new renters don’t have a shot at leasing a regulated apartment in the more desirable parts of the city, where landlords removed large numbers of units from rent regulation through serial rent increases until a 2019 state law barred the practice. In Manhattan, more than half of apartments in buildings with rent stabilized apartments are now unregulated, with tenants paying market rent, according to Rent Guidelines Board research.

The continued surge in market rents is a problem even for some of the most highly paid New York jobs. Tech workers, whose average wage is $135,000 — 50% higher than the citywide average — can afford only one in three market-rate apartments, according to a 2024 study by the trade group Tech:NYC and the real estate firm StreetEasy.

Entry-level tech workers, making an average of $75,000, can afford only 2% of studio and one-bedroom apartments, the study showed.

“The affordability concerns have only gotten worse in the tech community,” said Julie Samuels, CEO of the organization. “It is expensive up and down and the pay scale of tech companies and even people with high paying jobs have trouble finding apartments.”

The problem is threefold:

The city simply doesn’t have enough housing units to meet demand.

The rise in home prices and mortgage rates have trapped many New Yorkers in rentals, reducing what’s available on the rental market.

Sharply higher costs for items like insurance, property taxes and maintenance push landlords with buildings with both regulated and market rate rents to raise market rate rents to compensate for smaller increases in the regulated units.

The city’s vacancy rate is at a historic low of 1.4% as a result of an economic expansion that added 900,000 jobs between 2011 and 2023 and built only 350,000 new homes.

Market-rate rents declined during the pandemic as people fled the city, estimated at 350,000 by the U.S. Census. Since then the population has increased by at least 100,000, which corresponds with the escalation in rents for unregulated units.

The situation has been worsened in the last several years by first extremely low interest rates and then a fast rise as the Federal Reserve Board moved to fight inflation, Miller said.

In the pandemic, mortgage rates fell below 4%, which sent prices soaring for coops, condos and especially single family homes both in the city and in the nearby suburbs, making moving out of a rental difficult. Then when mortgage rates rose above 7%, buying became even more unaffordable. Sellers, who often have low cost mortgages, are able to hold out until they get the price they want.

“A key driver is why rents have gone up is because there are a lot of people camping out in the rental market who are waiting for mortgage rates to fall,” said Miller.

The data tracked by the Rent Guidelines Board, whose staff reports on rents and costs for landlords guide the board’s decisions on annual increases, shows how landlords with both regulated and market-rate units push up rents to offset the lower increases allowed on their regulated units. (By law, the board is supposed to vote to set rents based on the analysis, precluding a preordained “rent freeze.”)

Average rents in what the Board calls core Manhattan, where the vast majority of buildings have both kinds of apartments, rose 17% between 2019 and 2022, the latest data available. Citywide, the increase was only 7%. In The Bronx, the increase was also 7%.

Or consider Mamdani’s own building in Astoria, where he lives in a rent regulated apartment while earning a $142,000 salary as a state Assembly member and has additional income from his wife’s work as an artist.

According to a tax challenge filed by the landlord, the building’s 30 market-rate units generate $761,544 in annual rent and the 22 rent-regulated units $452,628. If the landlord were to seek to recover cost increases in order to maintain profits, all of that increased rent would have to come from market-rate tenants.

“As mayor, Zohran Mamdani will use every tool to keep rents down — that means freezing the rents of more than 2 million New Yorkers, fully enforcing good cause evictions, protecting tenants against price gouging, and cracking down on bad landlords,” said campaign spokesperson Dora Pekec. “For too long, city leaders, bought by real estate interests, have looked the other way as rents rise and working families drown. Zohran Mamdani knows relief won’t come from maintaining the status quo, it demands bold changes.”

But long term, Mamdani and real estate industry representatives say the solution is just more housing.

At Thursday’s mayoral candidate debate Mamdani said he would help keep down market-rate rents by building 200,000 new units of housing.

Agreed Basha Gerhards, executive vice president of policy at the Real Estate Board of New York: “To address the rapid growth of rent requires the construction of a significantly larger number of housing units because the affordability crisis is based on a supply crisis.”

Related