How did the public react to the Brooklyn Bridge?

Spanning the East River to connect Brooklyn and New York, the Brooklyn Bridge, designed and engineered by John Roebling, debuted in 1883 as the world’s longest suspension bridge. Yet many New Yorkers feared that a structure so large could never be safe.

Suspension bridges had a reputation for instability—known to collapse under their own weight, heavy traffic or strong winds, writes Ronald B. Tobias, author of Behemoth: The History of the Elephant in America. He cites the 1854 collapse of the Wheeling Suspension Bridge in West Virginia during a windstorm as an example. (Roebling had competed to design it, but had not been chosen.)

Still, on May 25, 1883, the day after its official opening, civic pride and curiosity prevailed: Some 150,300 pedestrians and 1,800 vehicles crossed the Brooklyn Bridge.

What changed to make people nervous?

One week later, on May 30—Memorial Day—tragedy struck when crowds swelled to an estimated 20,000 people and panic broke out on a narrow staircase near the New York approach. According to historian David McCullough in The Great Bridge, two opposing crowds collided, creating an impassable bottleneck. The chaos intensified when a woman fell, triggering screams and a stampede that left 12 dead and dozens injured.

How did P.T. Barnum’s elephants get involved?

In the aftermath, Tobias writes, many blamed the panic on the bridge’s safety—though the claim was later disproven in court. Meanwhile, the bridge’s convenience couldn’t be ignored, he adds, and its use soared. Trains crossing the span transported 9 million passengers its first year, and 18 million the next.

However, the tragedy left a shadow over the bridge’s reputation.

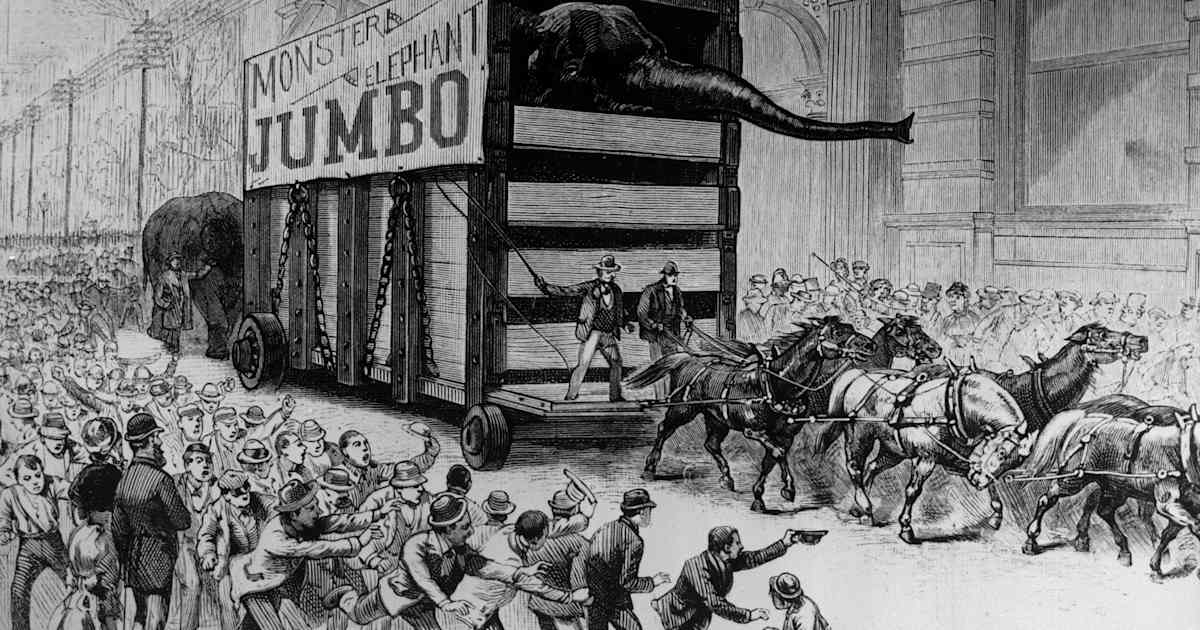

Seeking to restore public confidence, the bridge’s management company turned to showman P.T. Barnum. Known for his grand spectacles and traveling circus, Barnum had already offered to parade Jumbo, his prized 6-ton African elephant, across the bridge for a $5,000 “toll” fee. Initially declined, the offer was reconsidered after the Memorial Day disaster—this time with no toll required. “The directors of the New York Bridge Company felt they could convince the public the bridge was safe if the largest animal in the world walked across it,” Tobias writes.