“Monet and Venice” at the Brooklyn Museum is the first show in more than a century devoted to the Venetian works of the French master. It’s been a quarter century since New York City has seen such a generous showing of Monet’s work. Nineteen of Monet’s Venetian paintings are joined by some 80 other artworks, including meditations on Venice by John Singer Sargent, J.M.W. Turner, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. It’s enough to make one want to hail a gondola.

Monet went to Venice just once, and only for three months. He completed some 37 renderings of the city the Italians call La Serenissima, or “The Most Serene.” The Frenchman had long resisted painting Venice — then as now it attracted legions of tourists and tchotchke makers. The show’s curator, Lisa Small, explains that at Venice he captured the “evanescent, interconnected effects of colored light and air that define his radical style.”

When Monet arrived at Venice in October 1908 with his wife Alice he was already a 68-year-old eminence. The term “Impressionism” had gained currency following his painting “Impression, Sunrise,” which was exhibited in 1874. From his base at Giverny, in France’s north, he painted the plein air landscapes and water lilies that have made him among the most crowd pleasing of all artists — and a crucial figure in the development of modern art.

After finally arriving at Venice, Monet wrote “what misfortune not to have come here when I was younger, when I had all the boldness. Still … I’ve spent delicious moments here, almost forgetting that I was the old man I am.” The couple intended to return, but Alice died in 1911. Monet retreated to his studio and his garden. The Venetian paintings were finished in 1912, and exhibited to great acclaim. They were the last new works shown during his lifetime.

‘Water Lilies,’ by Claude Monet. circa 1914-17. Randy Dodson, via the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

‘Water Lilies,’ by Claude Monet. circa 1914-17. Randy Dodson, via the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

There are no tourists — or, for that matter, Italians — in Monet’s Venetian paintings. There is barely anyone at all. He treated the ancient city as a pastoral landscape, a waterworld of haunting absence and beauty. The foreground of “Palazzo Dario” is a watery expanse that leaves the viewer feeling that one is bobbing in the canal. The palazzo, a mix of Gothic and Renaissance styles, rises in the distance, half submerged and shimmering.

An engaging contrast is on display in Sargent’s “An Interior in Venice,” from 1899. There is not a drop of water to be seen. Instead, the environs of the Palazzo Barbaro’s grand salon are rendered darkly yet luminously. The Royal Academy of Art, where the painting usually resides, compares the palette to that of the Spanish master Diego Velázquez. Henry James was a frequent visitor to the palazzo, where he set “The Wings of the Dove.”

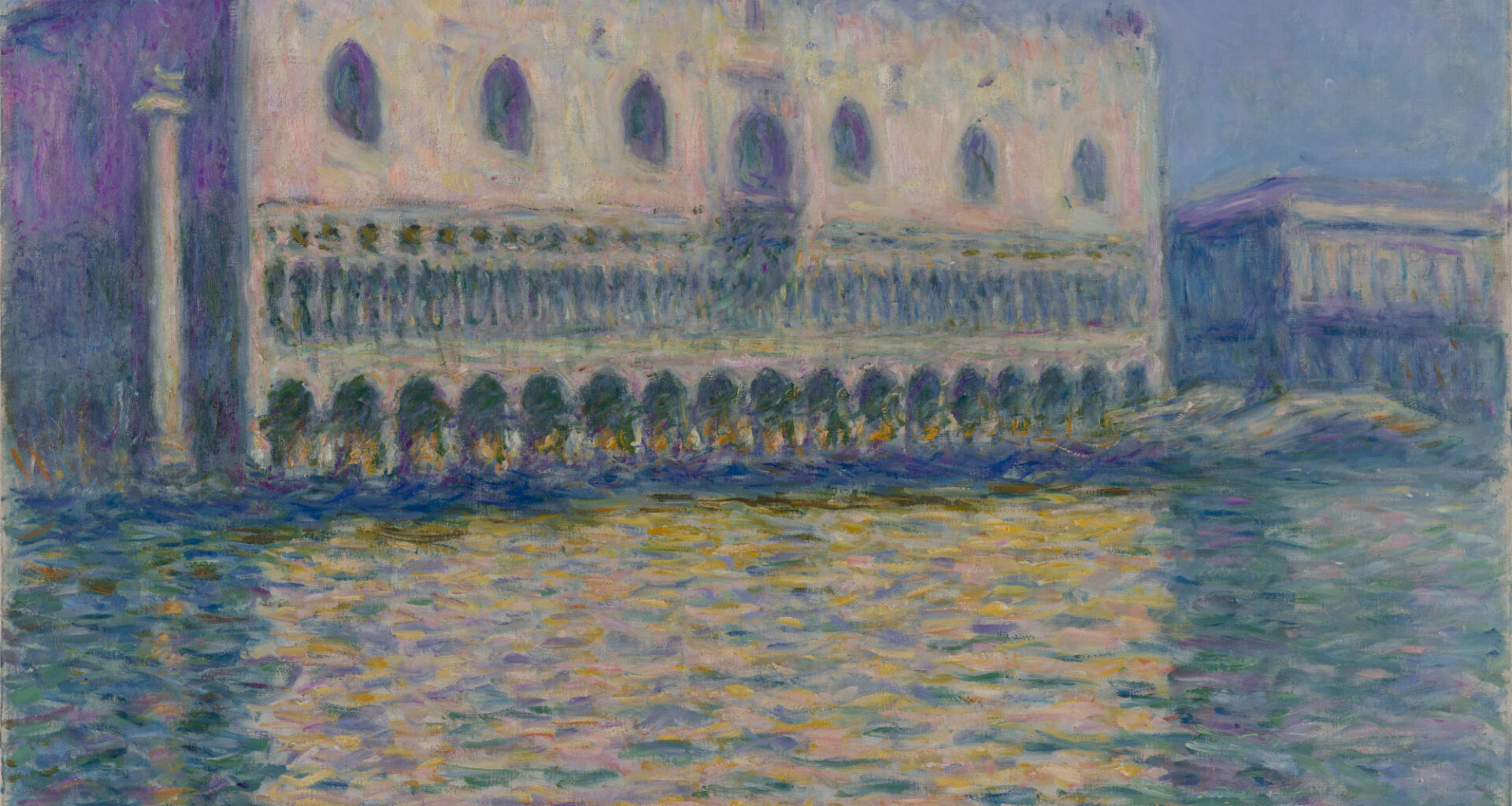

Monet’s “The Palazzo Ducale” captures how sunlight lands on water, almost floating on the waves of the Grand Canal. The Doge’s Palace dates from the 14th century, and echoes Venice’s great trading partners in the Middle East. Monet, though, is not a student of architectural style. He writes in a letter that “the palace that features in my composition was just an excuse for painting the atmosphere.” The atmosphere has the drama of a dream.

“The Palazzo Ducale” rhymes with Monet’s “Houses of Parliament, Sunlight Effect,” from five years earlier. Stationed at London’s Saint Thomas’ Hospital, Monet painted 19 versions of the Houses of Parliament — he would complete three versions of “The Palazzo Ducale” from the seat of a gondola. Here too the details of the Palace of Westminster fade in favor of a brooding vision of the city at night, the Thames running under a landscape of shadows.

A different approach is again offered by Sargent, who was born at Florence. “The Church of San Stae,” from a private collection, is hi-fi where Monet is lo-fi. Also painted from a gondola, Sargent captures a corner of the church from almost street level. The presence in the frame of the gondola as well as the canal and the church conveys the impression of a city that is lived in and human — the opposite of Monet’s abandoned metropolis.

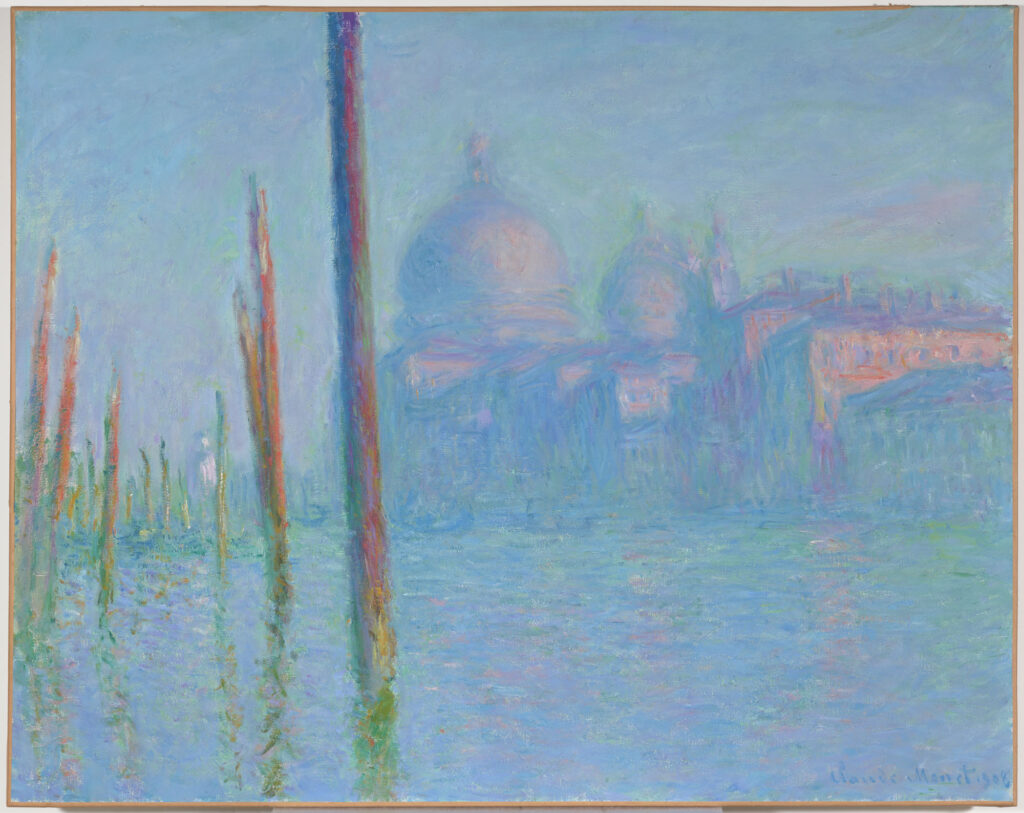

In “Le Grand Canal” Monet focuses not on a building but on the waterway itself. He finds the angle that elevates the aquatic artery to centerstage. Some 170 buildings line its banks. It was the Park Avenue of the Venetian Republic, showcasing the wealth of what was for more than 1,000 years a sovereign state. At the apogee of the Republic’s might it ruled a swath of what is now northern Italy, Crete, Cyprus, and a passel of Greek islands.

‘The Grand Canal,’ by Claude Monet. 1908. Randy Dodson, via the Fine

‘The Grand Canal,’ by Claude Monet. 1908. Randy Dodson, via the Fine

Arts Museums of San Francisco

A lovely echo of “Le Grand Canal” is on view in Monet’s “Japanese Footbridge, Giverny,” from 1895. Here the subject is not one of the world’s great byways but instead an intimate scene. Monet would paint this bridge repeatedly, influenced by prints from the Land of the Rising Sun. He expanded his own garden after seeing how the Japanese sculpted theirs at the 1899 World’s Fair at Paris. The bridge’s curve is captured in a rounded reflection.

The Brooklyn Museum has collected three of Monet’s water-lily paintings, and they are every bit the equal of the formidable display at Paris’s Musée de l’Orangerie. Not painted at Venice, their landscapes of lilies floating nevertheless feel connected to the landscape of that waterlogged city. The relation of solid to liquid, and the wonder of buoyancy, all speak resonantly to palazzos, flowers — and people.