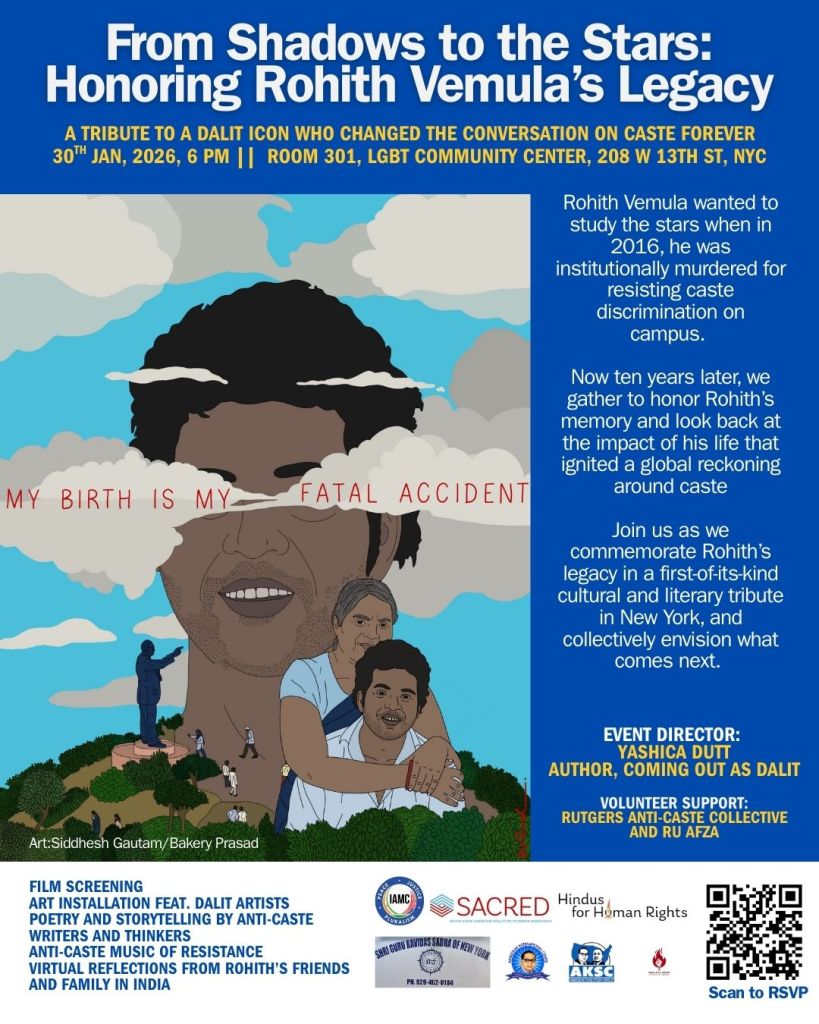

Yashica Dutt can’t forget when a graduate student died by suicide in India after denouncing caste discrimination. The student, Rohith Vemula, took his life in 2016 after his university suspended and harassed him and other activists from the Dalit caste, once called “untouchable,” the lowest tier in Hindu social hierarchy.

Now Dutt wants New Yorkers to remember this legacy.

She had just finished graduate studies in journalism at Columbia University when the tragedy ignited protests nationwide and propelled a movement for Dalit rights. Dutt would later partly credit Vemula with driving her to finally share her own story: “Coming Out as Dalit.” In the book, she chronicled her secret life passing as someone from a higher caste in order to survive in her homeland, secure a good education and even rent an apartment.

This Friday, she and others advocating to end caste oppression are hosting an event in Manhattan commemorating the anniversary of Vemula’s death — and highlighting Dalit culture against the backdrop of renewed focus on South Asians in New York. “From Shadows to the Stars” will include a film screening, an art installation featuring Dalit artists and a conversation with anti-caste poets and thinkers.

Reclaiming Dalit culture — and the table

Dutt’s hope is for this to be the first of many events celebrating Dalit culture, “not to be confused with just Hindu upper-caste culture.” That will include a new perspective on desi food, from the Indian subcontinent. “Usually, if you go to a desi event you will have lassi or chai or samosas, but we want to present the kind of food that is important to Dalit people.”

That includes beef, which is politically fraught in India, which has seen an increase in killings by Hindu nationalists of members of Dalit or Muslim communities suspected of slaughtering cows. It also includes Indo-Caribbean dishes, which are tied to the history of indentured labor from lower-caste people brought to the region from India.

Another goal is to create solidarity with Black New Yorkers and others whose history shares parallels with caste discrimination. And she said the event is also about carving out space for Dalit people who have long been pushed to the margins.

Courtesy of Yashica Dutt.

Courtesy of Yashica Dutt.

“This is a time of reckoning for South Asian communities and we cannot leave Dalit communities behind,” Dutt told Epicenter NYC, referencing local politicians’ greater engagement with the diaspora after Zohran Mamdani, a nearly unknown state assemblyman from Queens, was elected mayor last November.

In an article Dutt wrote during the mayoral campaign, she wrote: “As an assemblymember, Mamdani, who comes from a mixed dominant-caste background (his mother, Mira Nair, is from a dominant Khatri caste, and his father, Mahmood Mamdani, comes from a Khoja merchant caste background), has been vocal about his support for the anti-caste movement. In 2021, Mamdani appeared on a panel with anti-caste activist Prachi Patankar and emphasized the need for leadership from Dalit and marginalized caste communities to counter the rise of Hindu nationalism.”

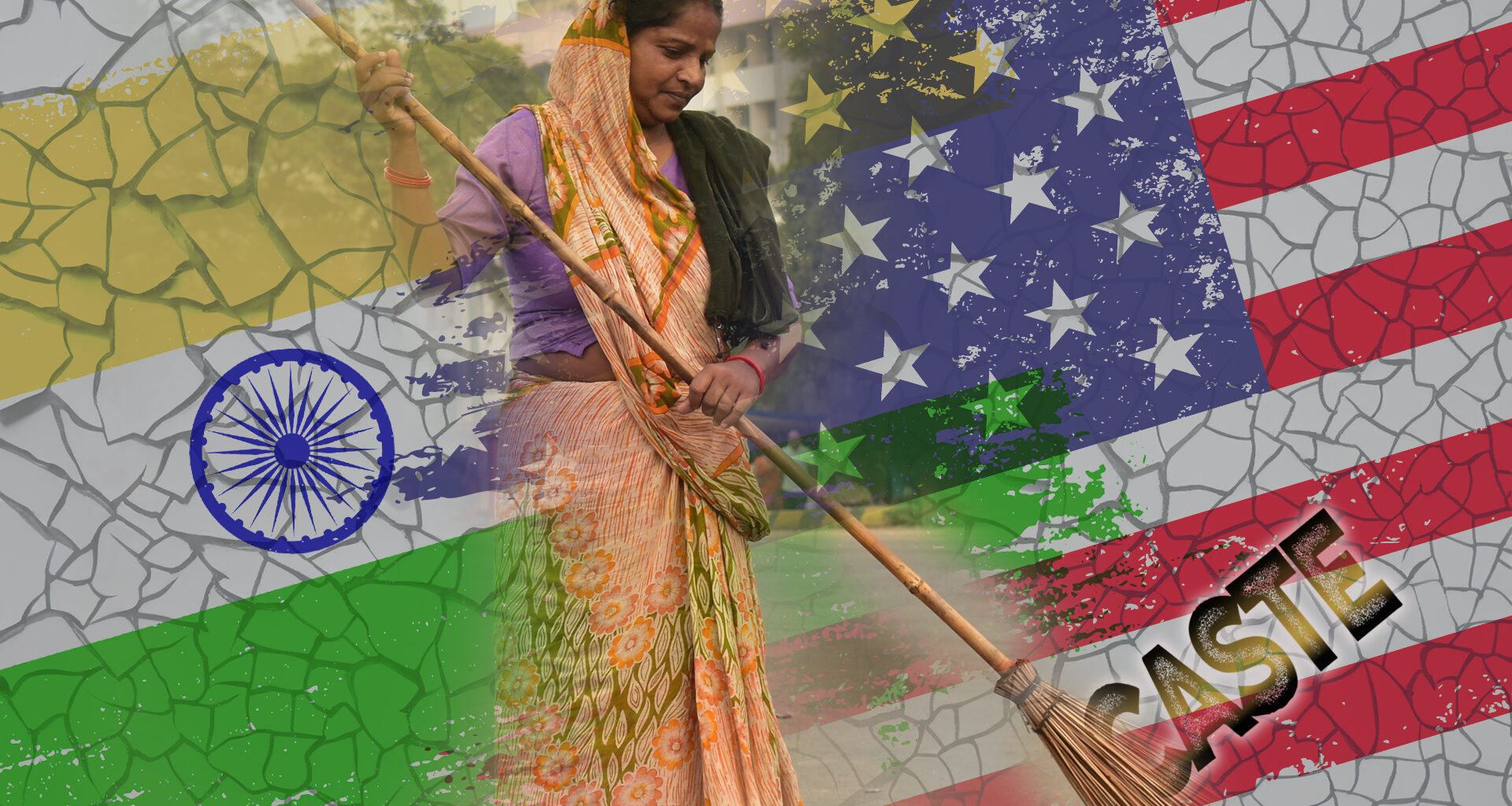

Caste in your city

The city provides some degree of distance from the discrimination Dutt and others face back home for being born into a certain family. But only some. A recent paper from Cornell Law School alludes to often underreported accounts of caste discrimination in everything from housing to employment in centers of the South Asian diasporas in New York and New Jersey.

And there’s still an active civil lawsuit related to the majority-Dalit men allegedly lured from India to build a temple in New Jersey for about $1 an hour under dangerous conditions. The Hindu sect named in the lawsuit, known as BAPS, is tied to India’s ruling party and also runs a temple in Flushing visited by politicians from former Mayor Adams to Mamdani during his campaign.

At the same time, opponents criticized Mamdani for co-sponsoring a bill to ban caste discrimination, calling him “Hinduphobic,” as New Lines Magazine reported. The bill, sponsored by Assemblyman Steve Raga and cosponsored by Mamdani and several other lawmakers, is currently in an Assembly committee. It would add caste as a protected class in New York’s laws covering employment, housing and public accommodations.

Raga said in an email he introduced the bill because New Yorkers shouldn’t face unequal treatment “because of a rigid social hierarchy they were born into.” He said many constituents have reported caste discrimination but hesitate to come forward because caste is not explicitly protected under state law.

Caste in your community

You might not call it caste, but odds are, your community has its own social hierarchy. Similar patterns of exclusion show up far beyond South Asia, according to civil rights organization Equality Labs. Raga pointed to caste-like hierarchies among the Burakumin community in Japan, the Osu in Nigeria and groups in Senegal and Mauritania.

In New York, he said, inherited status and quiet, community-based exclusion continue to shape people’s access to housing, jobs and dignity. “This bill acknowledges those realities without targeting any religion or culture,” Raga said. “It is focused on one thing: protecting people from discrimination.”

In this city of immigrants, many bring with them attitudes from back home that reinforce caste hierarchy. This includes making nannies or housekeepers sit separately for meals or use a different bathroom from the family they care for.

“This discrimination against people who work in our homes, it is such a big part of caste,” Dutt said. She would know: She comes from a family that once worked cleaning toilets, a job that in India is believed to pollute anyone who touches the workers. Sometimes, she said, Dalit workers are given food on a separate plate that is thrown away after a single use.

One of the biggest complaints she hears from members of the South Asian diaspora is that here, unlike back home, they have to do their own household work. When asked about similar comments from some Latin American immigrants used to different lifestyles in their home countries, she said it reflects a shared “entitlement to the labor of lower-class people,” a belief that certain people exist to serve others.

Yashica Dutt, journalist and anti-caste activist, highlights how caste discrimination can show up in who is expected to serve. Credit: Levi Mandel

Yashica Dutt, journalist and anti-caste activist, highlights how caste discrimination can show up in who is expected to serve. Credit: Levi Mandel

What you can do

So what can you do? Start by noticing these patterns in your own community. But more is needed, Dutt said: “We can’t leave it to the people who are feeding off of the labor of the exploited.”

She said bringing Dalit Indo-Caribbean people and other Dalits together can open the door to broader alliances with other marginalized groups. “People hear us more because you can’t just ignore one group and say ‘Oh, it’s just Dalit people, or it’s just the oppressed people from Latin America,’” she said.

She urges New Yorkers to learn more about the caste system. If you’re not from the South Asian community, be aware of the subtle ways that caste shows up, she said. Questions about where your family is from or even the reasons you’re vegetarian or eat meat are often coded caste inquiries.

Dutt also urges you to ignore the idea that it’s racist to talk about caste discrimination if you’re not South Asian. “That is something that certain Indian American groups have tried to push,” she said. As a Dalit person, she believes that when you question or call out caste, “you’re only helping us, you are empowering our voices, you are giving solidarity to the oppression that we experience in these spaces.”

Dutt said she hopes people learn what they can about caste, but understands everyone has limits, especially in this political climate: “Be as aware as we can and do what is possible for us,” she said. “But also understand that collective solidarity is where it is at this moment.”

Raga said New Yorkers should know that caste discrimination “does happen here, even if it’s not always visible, and that naming it in the law matters.” He encouraged neighbors to connect with advocacy groups, listen to affected communities and talk to their state representatives.

“A6920 is about providing clear legal protection,” he said, referring to the bill. “But lasting change also comes from collective action.”