Nearly 70 years after the Dodgers broke the hearts of Brooklyn fans by leaving for Los Angeles, two Israeli basketball players are joining the borough’s current team, stirring echoes of a complex and emotional sporting legacy that spans generations of Jewish life in New York.

In the 1950s, one out of every three Brooklyn residents was Jewish. They included those who fled Europe before the Holocaust and survivors who arrived afterward. Like their neighbors, they were first and foremost fans of the Brooklyn Dodgers — the only sports team ever truly identified with Brooklyn. Not with New York, not with Manhattan or New Jersey — just Brooklyn, the diverse and history-filled borough that stood apart from the rest of the city.

4 View gallery

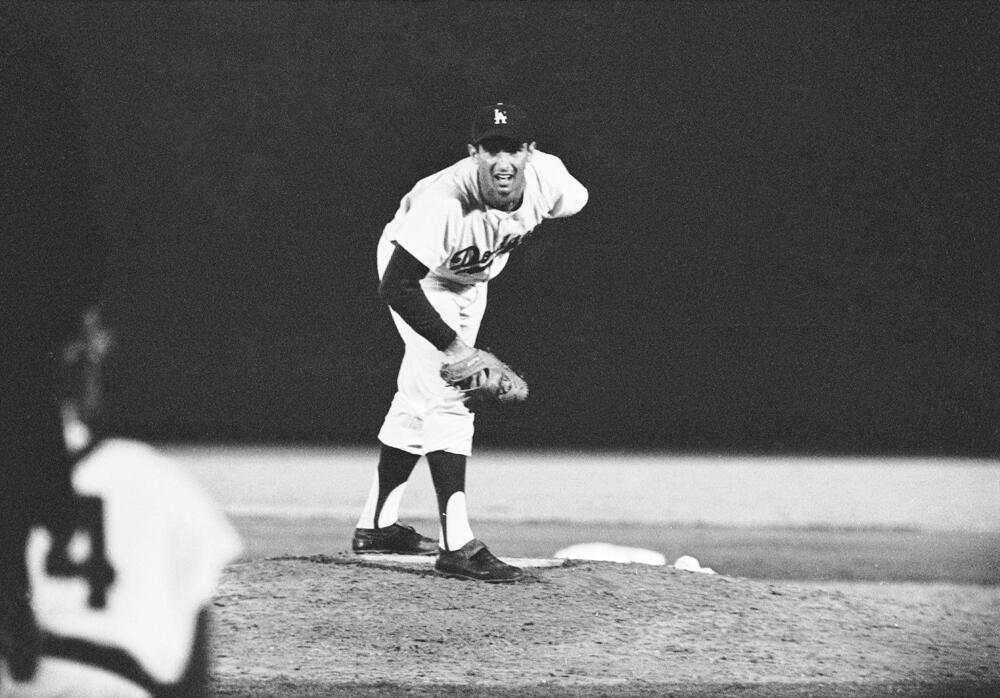

Sandy Koufax

(Photo: Gettyimages)

In 1955, a 19-year-old left-handed pitcher named Sandy Koufax joined the Dodgers. A Brooklyn native and widely regarded as the greatest Jewish athlete of all time, Koufax helped turn the Dodgers into the team of Jewish America.

Three years later, team owner Walter O’Malley moved the Dodgers to Los Angeles after New York City refused to grant him the specific plot of land he wanted for a new stadium, offering a different site instead. Los Angeles officials quickly provided O’Malley with a large parcel and generous tax incentives. The move tore Brooklyn’s heart out and took it west.

To this day, the relocation remains one of the deepest wounds in American sports fandom. Parents in Brooklyn raised their children not to forget and not to forgive — neither O’Malley nor New York City. The Dodgers’ departure shattered Brooklyn’s sporting identity, leaving the city’s most populous borough an orphan. But new generations were born, and they needed a team to root for.

After the Dodgers left, many Jewish families joined the broader “White Flight,” the postwar migration of middle-class white residents to the new suburbs. In eastern Queens and on Long Island, Jewish families found affordable homes and convenient access to Shea Stadium, the home of the New York Mets.

And since no one from Brooklyn could ever bring themselves to support the Yankees, the Mets became the natural heirs to the Dodgers in the hearts of Jewish New Yorkers — a loyalty that endures to this day.

Comedian Jerry Seinfeld, a lifelong Mets fan, famously channels his disdain for the Yankees through his television persona. Within New York’s Jewish community, there’s an old saying: “One hundred percent of old Jewish men would run over their mothers to see the Mets finish ahead of the Yankees.” The humor reflects a genuine rivalry rooted in decades of neighborhood pride — and the lingering sense of betrayal that began when the Dodgers left town.

That history sets the stage for the very different reality facing Danny Wolf and Ben Saraf, two Israeli players joining the Brooklyn Nets this season. The Nets are not the Dodgers. They didn’t even originate in Brooklyn — the team relocated from New Jersey, where it never developed a particularly loyal fan base.

Still, aside from the two Los Angeles teams, there may be no NBA franchise where Wolf and Saraf could feel more at home than in Brooklyn.

Today, nearly half a million Jews live in Brooklyn, out of a total population of 2.7 million — large enough that the borough alone would rank as the fourth-largest city in the United States. But the composition of that community has changed dramatically since the 1950s.

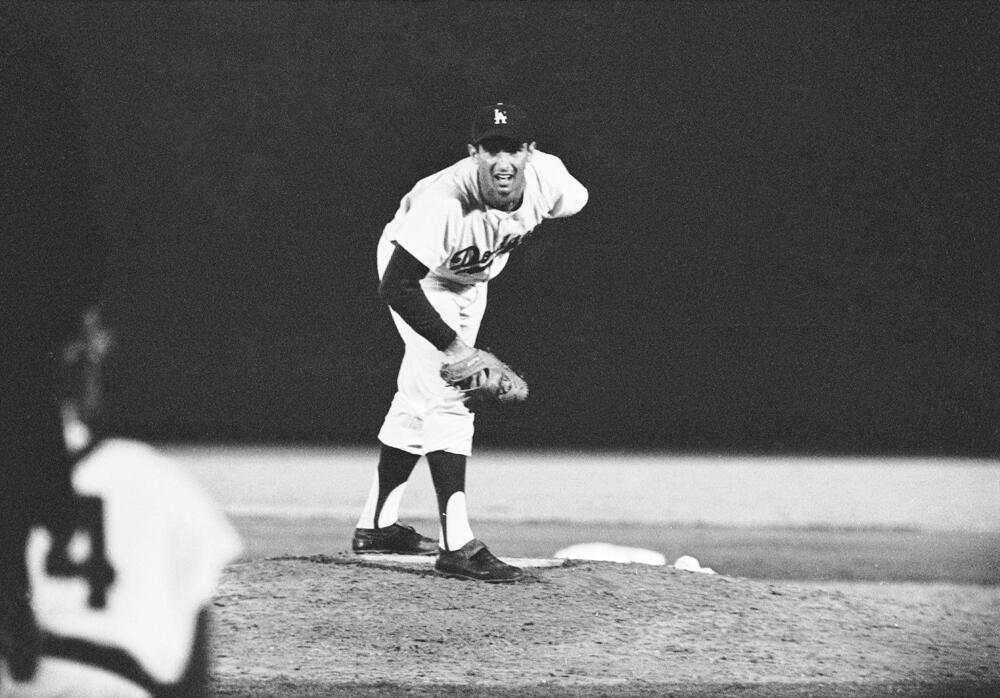

4 View gallery

Ben Saraf and Danny Wolf

(Photo: Harry How / GETTY IMAGES NORTH AMERICA / AFP)

More than half are ultra-Orthodox, concentrated in Borough Park and Crown Heights, where attitudes toward professional sports differ sharply from those of the past. Traditional Jews live mainly in Midwood and Flatbush in southern Brooklyn. Reform and secular Jews are clustered in western neighborhoods such as Park Slope. Immigrants from the former Soviet Union and Israelis are scattered along the southern coast.

Given that diversity, when the Nets drafted two Jewish players this year, observers noted that the decision carried a business dimension as well. In a city with roughly 2 million Jews, and with a quick subway ride from Times Square, the Barclays Center can count on Israeli tourists to fill the stands.

Still, even the Jewish fans who come to cheer Wolf and Saraf are unlikely to become loyal Brooklyn Nets supporters. For many, that would border on sacrilege. Jewish New Yorkers, like much of the city’s population, are Knicks fans — a shared identity that transcends faith and neighborhood. Jews in particular feel a special bond with the Knicks, not only because of the team’s deep history but also because, as many joke, both Jews and Knicks fans are accustomed to suffering.

The Knicks last won an NBA championship in 1973 under coach Red Holzman, the son of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. Holzman, now enshrined in the Basketball Hall of Fame, remains a revered figure at Madison Square Garden.

In the team’s early years, Jewish players were a defining presence. In 1946, six Jews were on the Knicks roster, and four started regularly: Oscar “Ossie” Schectman, Leo “Ace” Goldstein, Sidney “Sonny” Hertzberg, and Ralph Kaplowitz.

4 View gallery

(Photo: Sarah Stier / AFP)

Just as antisemitism in early 20th-century America had pushed Jews to found Hollywood when they were excluded from other industries, Jewish youth in New York found refuge and pride in basketball — through the Knicks.

Even today, when the Nets host a cross-town matchup, they often feel like visitors. The Knicks’ dominance in the city’s sports identity is cultural as much as athletic. “It’s not the Nets’ fault,” said one longtime fan. “New York belongs to the Knicks.”

The Nets moved in 2012 from the swamps of the Meadowlands in New Jersey to the gleaming Barclays Center on Atlantic Avenue, part of a major urban development project. Team executives hoped to build a new, loyal Brooklyn fan base.

On paper, there was no reason they couldn’t succeed. Brooklyn residents take immense pride in their borough, and basketball remains especially popular within the Black community, which makes up more than a quarter of Brooklyn’s population.

4 View gallery

(Photo: AP Photo/Peter K. Afriyie)

Over the years, the franchise signed marquee names — from Kevin Durant to James Harden — but the results were mostly disappointing.

Then came the controversy surrounding Kyrie Irving, whose promotion of antisemitic material drew outrage in a city that is home to the largest Jewish population outside Israel. The Nets quickly traded Irving to Dallas and began a full-scale rebuild.

Now, as Wolf and Saraf join the roster, some fans see a symbolic opportunity for renewal.

Perhaps, nearly 70 years after the Dodgers’ departure, the Nets can fill even a small part of the void left in Brooklyn’s sporting soul. It would be poetic if two Jewish players helped make that happen — in an arena built precisely on the site where Walter O’Malley once wanted to construct a new stadium for the Brooklyn Dodgers.