Technocracy viewed its dream as a form of social engineering with society like a biological organism that can be behaviorally conditioned. In a mockup of the technocratic state, Technocracy Incorporated dedicated an entire department to “social relations.” Every facet of society was to be quantified, processed, and optimized for efficiency. Each citizen would be surveilled in their habits to ensure the smooth processing for the greater industrial organization. A new seven-day work week was proposed to allow for non-stop production.

From this principle, a vision of technocratic government emerged. First, all industries would be centralized into a few large-scale enterprises owned by the state. Each would be administrated by a board of technical experts. Second, the state would be exclusively bureaucratic and non-democratic. Third, each citizen would be granted a universal basic income based on production quotas. Fourth, prices and money would be phased out and replaced by energy vouchers. And last, all politics and parties would be abolished. There would be no officials other than those experts who lead industry.

Yet, how it would actually get to governing was hardly clear. Despite being deeply elitist, Technocracy Incorporated adopted a mass character. Scott peddled in fantasies, and so he imbued the movement with a folk-like ethos through popular rallies, local chapters, and pamphleteering. Because politics in the 1930s was populist and mass-led, technocrats understood the pull of the crowd. They were also competing with the New Deal. Yet, under the surface, technocrats understood their system was more about creating a new priestly class of experts than anything representative. These technicians were to lead society because they were biologically superior. As one 1937 essay in Technocracy Digest put it, “upon biologic fact, theories of democracy go to pieces.”26

The writer Harold Loeb summarized the core belief behind technocracy as follows: “Technology is the revolutionary agent of our period.”27 In a time of intense class and national conflicts, the technocrats of the 1930s did not view workers or nations as holding the future. They fashioned themselves as revolutionaries working in the interests of a different subject: technological progress. And like all revolutionary movements, they had a deep messianic belief that only they possessed the capabilities to save society from coming destruction.

In truth, the technocrats had overestimated the power of science and industry in their time. Technological systems were not developed enough then to measure and direct society mathematically. Nor did the original movement possess the expertise to even pursue this dream, because few actual engineers and scientists filled its ranks. But today, the appeal of technocracy finds itself in a different world. We are incessantly surveilled, quantified, and made malleable through our behaviors online.

Technocrats no longer need to persuade the masses to enact their vision. Owning the lion’s share of the world’s capital and influence, they can effectively work in silence and act as if beholden to no one. In the twenty-first century, core ideas of technocracy’s old dream have been revived and given new life.

Technocracy Today

In the twenty-first century, the definition of technocracy has expanded well beyond the scope of the short-lived 1930s movement. It has been used to describe the EU’s European Commission, China, Singapore, and Italy during the COVID pandemic. In everyday conversation, “technocrat” is often used as a catch-all term for “non-political expert.”

Given historically low institutional trust, the appointment of non-political experts has become a common strategy by political parties to repair their image. Political scientist Sheri Berman has argued that, in times of popular anger, few would make the case for oligarchy. Rule by an unelected technocracy, however, is a less offensive stand-in.28 Appealing to technocrats provides the state with an attractive means of shoring up legitimacy during crisis. The Trump administration’s recent “Gaza peace plan,” for example, is rife with technocratic language—stipulating that the territory will be governed under the “temporary transitional governance of a technocratic, apolitical Palestinian committee.”

But while definitions of technocracy today cast a wide net, the original idea is finding a second life in Silicon Valley. It is among the tech elite that technocracy takes on actual, ideological substance that echos the movement of old.

In 2009, tech venture capitalist Peter Thiel outlined his new belief on politics in an op-ed for the Cato Institute. He still called himself a libertarian, but wrote that he no longer believed democracy and freedom to be compatible.29 Politics, he argued, had failed in providing new horizons. Instead, Thiel was convinced that tech entrepreneurs now had to escape politics. They had to get away from the “unthinking demos that guides so-called ‘social democracy.’” To put it differently: he had come to the conclusion that actual people were in the way of the technological future.

For Thiel, technology was in a deadly race with politics. This, in his view, had suffocated innovation and led to widespread stagnation. He speculated that the future may depend on “the effort of a single person who builds or propagates the machinery of freedom.” This would be the only way to make the world safe again for capitalism.

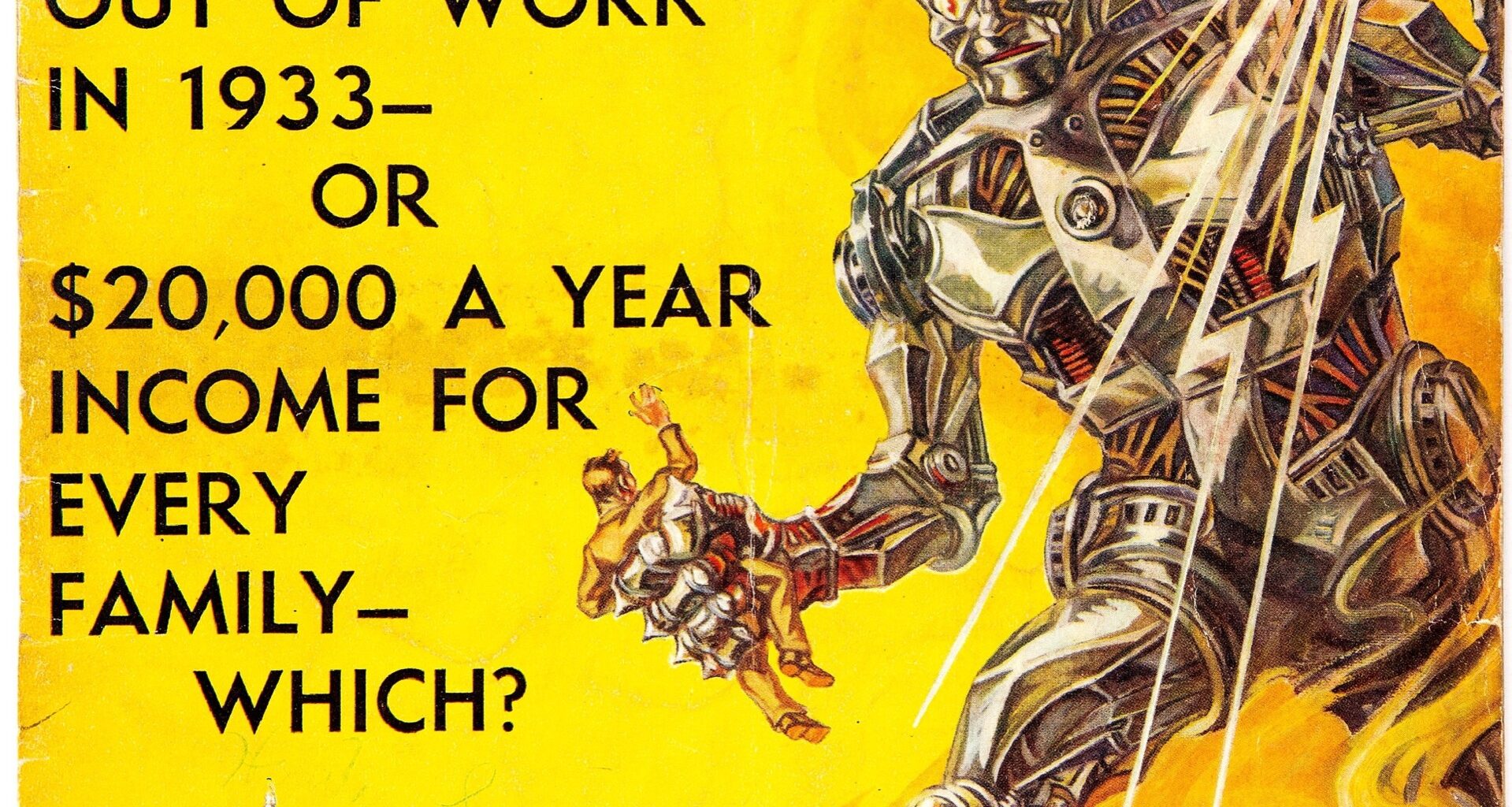

Thiel’s thoughts would go on to be instructive for tech elites over a decade later. Many of his allies now occupy top positions within politics and Silicon Valley, like OpenAI CEO Sam Altman, neoreactionary thinker Curtis Yarvin, and even the current vice president, JD Vance. In Thiel’s worldview, technological progress is simply too important to be left to democratic society. His beliefs echo the technocrats of almost a century ago, who viewed themselves as in the wings, ready to take over when democracy collapsed. As their 1933 statement read, “technocracy stands ready with a plan to salvage American civilization, if and when democracy… can no longer cope with the inherent disruptive forces.”30

However, unlike the movement of old, twenty-first century technocrats do not wish to replace capitalism. Instead, they see themselves as the chosen elite destined to save and steer it. And within this belief, strangely enough, even capitalist competition itself is viewed with suspicion. In a 2014 op-ed for the Wall Street Journal, Thiel calls economists’ obsession with competition a “relic of history.”31 Monopolies drive progress, he argues, and they are a natural consequence of the accumulation of capital. This is his self-described “idée fixe”—an endpoint he is “obsessed with”—and he co-hosted an event with Altman on the subject in 2014. The reverence toward monopolies closely resembles the old technocracy movement’s desire for top-down centralization of industry.

Such ideas have been taken to their logical conclusion by “Dark Enlightenment” thinkers, especially Curtis Yarvin. A techno-monarchist, Yarvin is a believer in transforming the state into a corporation led by a CEO-like monarch with a court of (presumably) Silicon Valley aristocrats. Yarvin is close to Thiel, calling him “fully enlightened” on this question.32 As a nod of agreement, Yarvin’s start-up was also funded by Thiel’s VC firm. The “Dark Enlightenment” circle includes fellow travelers like billionaire Marc Andreessen. In 2023, he argued in his venture capital firm’s manifesto that concerns over inequality, environmental degradation, and social atomization are the complaints of “decels” (decelerationists), who are irrationally against technological progress.33

Such elitist, anti-democratic, and monopolist views circulate within a complex web of ideologies that animate Silicon Valley. They loosely fall under the umbrella term of “Rationalism,” but also overlap with AI accelerationism and effective altruism (EA). EA found its voice on message boards like LessWrong, where users shared utilitarian solutions to long-tail civilizational risks. In what would be the movement’s deathblow, EA’s most famous proponent, crypto mogul Sam Bankman-Fried, viewed his embezzlement of customer funds as preventing long-term “risks.” He rationalized that saving his over-leveraged venture capitalist firm with others’ money, without their permission, was socially optimal.

This self-inflicted wound to EA ultimately exposed the limitations of Rationalism generally. As Omar Hernandez observed in “Capitalism, Rationality, and Steven Pinker”, the Rationality community is the philosophical ecosystem of twenty-first-century technocrats.34 What binds them together is the goal of “removing cognitive biases,” as if parsing through bad code in the social body, done through quantitative assessments of the world. This quantitative view of the social world persists among tech elites. It is their main leverage for accruing power: the endless collection of personal data. On this basis, they lobby the state to argue that they alone possess the toolkit for social prediction. Some companies are shamelessly open about pushing this case—like Palantir, whose name is taken from an all-seeing orb that can predict the future in Lord of the Rings. The dream of today’s technocrats is coached in the same language as almost a century ago: that all social processes are measurable and can therefore be efficiently optimized and predicted.

Among all tech companies, Palantir has used this leverage most effectively. It represents the leading strategy for power nowadays among tech elites, namely integration with the state through data sharing and lucrative contracts. Palantir now provides data for Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), intelligence for lethal force on the Ukrainian battlefield, machine learning for the Department of Defense, and citizen databases for the IRS and other government agencies, among other functions. As an integral part of the American state, it is one of the few contractors immune to the Trump administration’s cost-cutting. Alex Karp, its CEO, justifies his company’s mission in explicitly Americanist terms, arguing that the fusing of state power with Palantir and other tech giants is necessary to—as Co-Founder Joe Lonsdale put it—“save Western civilization.” Other companies, like OpenAI, Meta, and Google, have taken cues from his strategy of state alignment. In December 2025, the US Department of War announced that it will be integrating with Google’s Gemini AI platform.35

But not all technocrats are pleased by this statist turn. Elon Musk, for one, tried to enter politics and then left abruptly without achieving any of his hyperbolic cost-cutting promises. He now believes only AI can save America.36 Others take an equally cynical view, and echo Thiel’s original concern that politics is incompatible with technological progress. The proposed alternative path forward is instead to exit and build power on the margins, ready to swallow a weakened American state when the time comes. This case was first made by tech investor Balaji S. Srinivasan in a 2013 speech at startup accelerator Y Combinator. America was “outdated and obsolescent” like Microsoft, he argued, and it was time for Silicon Valley to secede.37 The speech won roaring applause from the audience.

More recently, Srinivasan has been proselytizing a new belief that he likens to “tech Zionism.”38 Tech elites had to exit democracy and settle sovereign territories of their own. These peripheral islands of tech utopianism would in time unite, eventually accruing enough capital and power to challenge the nation-state. They would oversee a new tribe of loyal citizens dressed in matching gray. “If you see another gray on the street… you do a nod. You’re a fellow gray.”39

This aesthetic choice, it must be said, is ridiculously on the nose: gray was also the color palette of the 1930s technocracy movement. Srinivasan’s ideas could easily be ignored if he was a pariah in the tech world, but he is not; the book explaining his worldview, The Network State: How to Start a New Country (2022) is quite popular. Andreessen has praised Srinivasan, in Rationalist terms, saying he “has the highest rate of output per minute of good new ideas of anybody I’ve ever met.”40

Technocracy today may have different strains of thought, but they ultimately converge on a pseudo-religious millenarian view of the world. What they disagree on is how to best achieve it. Given that technology is again being put forward as the sole mover of history, it is unsurprising that its wealthy beneficiaries view themselves as the rightful heirs of the coming social transformation. The belief is not so far removed from Howard Scott’s—who argued that “engineers and mechanics created this civilization, so they will eventually dominate it.” So, too, do today’s technocrats view themselves as the creators of this current civilization, and hence see it as their right to dominate it.

Twenty-first-century tech elites may not even know of the old technocracy movement, but have revived many of its ideas. Gone are the pomp and spectacle of rallies, however, since popular persuasion is no longer needed. Equally missing are the critiques of capitalism, since capital accumulation now benefits the new technocrats. Instead, we are left with pure technocratic technique, organizing numbers and data, to give substance to the old dream. Whatever its fantasies, they are nonetheless still tied to economic realities, and will live only so long as tech stocks soar.