A 130-year-old Baptist church in Manhattan has become a model for how to revitalize aging congregations through creative land use and partnerships.

Judson Memorial Church was founded in 1890 by Edward Judson to honor his father, missionary pioneer Adoniram Judson. The church’s Italianate-style building, which stands near Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village, was completed in 1893.

Today Judson is affiliated with the American Baptist Churches, the United Church of Christ and the Alliance of Baptists. Across all denominational lines, however, the church has become a go-to model for creative adaptation in faith communities. Its work was featured at an Oct. 21 “Faith-owned Property Summit” presented by Bricks and Mortals, a New York nonprofit working to help faith communities make the most of their physical resources.

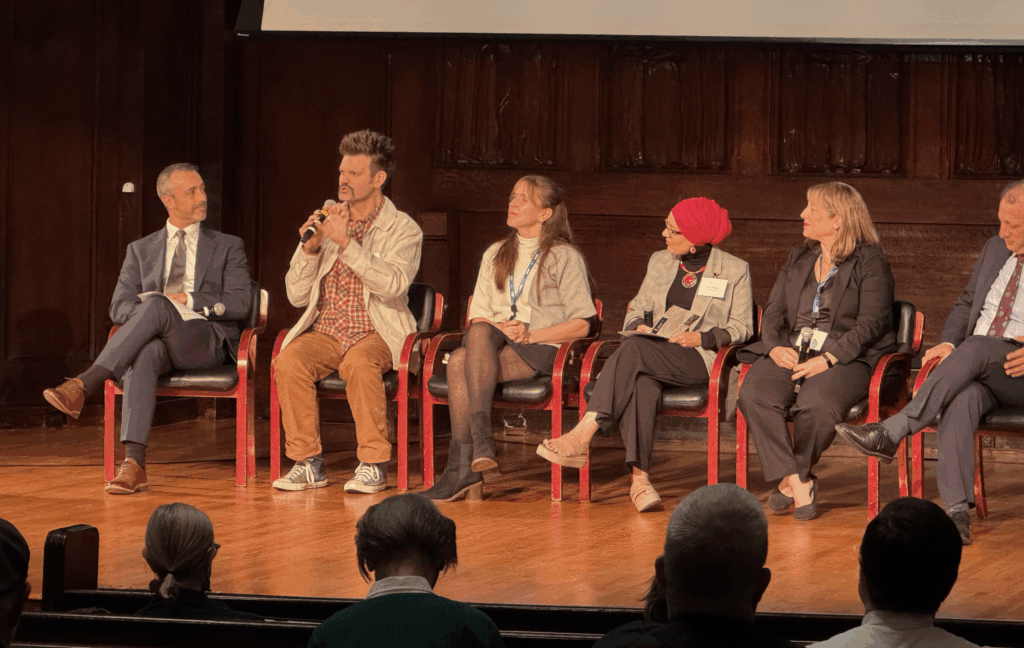

Pastor Micah Bucey participated in a six-person panel on creative uses of faith properties. One of Bucey’s co-presenters, Anne Marie Witchger, priest at St. Mark’s Church in the Bowery, grew up at Judson and was influenced by its ministry. Today, she leads an Episcopal congregation that also is finding new uses for its space — with inspiration from Judson.

Micah Bucey speaks as moderator Taylor Aikin, an architect who chairs the Bricks and Mortals board; Debbie Alontaser, founder of Bridging Cultures Group; Annette Powers, director of synagogue strategy for the UJA Federation of New York; and Brad Lander, New York City comptroller, look on.

Aikin said Judson Memorial Church “is so often the example we hear when we talk about enthusiastic space sharing.” Program notes mentioned the church’s “hyper space use.”

In addition to the primary congregation that has inhabited the building for more than a century, the building now houses an array of nonprofit groups that “push the boundaries for justice, art and worship.”

‘Extravagant enthusiasm’

The beginning point is that “Judson has always had a theology and a spirituality of extravagant enthusiasm and a theology and spirituality of yes,” Bucey said. “We do not live in the space of scarcity. We always live in the space of abundance.”

“We do not live in the space of scarcity. We always live in the space of abundance.”

Building on that legacy, “our holy trinity is unfettered creativity, radical social justice seeking and expansive spirituality,” the pastor said, explaining that 130 years ago Judson intentionally placed the church at the intersection of an affluent community and an immigrant community. “He wanted Judson to be a space that could be funded by the folks who lived above the park so that he could be a space that welcomed in the Italian immigrant … (who) at that time had not been welcomed into the privileges of whiteness.”

Micah Bucey

Although founded as a Baptist church, the building looks more traditionally Catholic, Bucey explained. “That’s very intentional. He wanted (the) church to look like a Catholic church specifically so the Italian immigrants who at that time were predominantly Catholic would say, ‘That place is safe for me and I can go inside.”

The same remains true today, even as the community around the church has changed.

“We have basically always, and imperfectly, stumbled through continuing Edward’s vision, which is to always be asking the community around us, the population that fills the space around the church, what they need, not starting from a place of scarcity and thinking, ‘We’re running out of money, our building is crumbling.’”

In the 1960s, church leaders went into the artist community nearby and asked what they needed. “They said, ‘We need space. We need free space where you’re not going to censor the art we bring into the space.’ And so that then unfolded into several decisions the congregation made.”

The first big change was removing all the pews from the sanctuary to make it a more flexible space. “Before that became a little more in vogue, Judson congregation said, ‘Why are we filling this space, this huge space, with these pews nobody wants to sit in anyway? Why are we filling this space with that when we can take out all these pews and create a beautiful dance floor?”

From that change, the church became the birthplace of postmodern dance, Bucey said. “It then became the birthplace of the Judson Poets Theater, which at that time was part of the burgeoning Off-Broadway movement.”

Other movements and groups followed, from an AIDS Resource Center to work with immigrants and the transgender community.

Asking the community what it needs

All these came into being because the church kept asking the community about its needs, Bucey said.

More recently, though, church leaders realized they had neglected upkeep on their own building while opening the doors to all. The attitude was “don’t worry about the building, let the building do what the building does. Just fill it with programs.”

What he and others now understand is those programs cannot continue if building maintenance keeps getting deferred.

What he and others now understand is those programs cannot continue if building maintenance keeps getting deferred.

“We’ve never told people what we need. And that’s not relationship. That’s actually still a colonialism project, right? Us going out and sort of saying, ‘You need us. So what do you need? Let us ask you.’ So now we have actually learned from some of our past mistakes and some of the amazing work that’s been done, and now we are actually saying to the folks who are using our space, ‘Hey, do you see the crumbling ceiling? Can we apply for a grant together? What are the connections you have?’

“We wanted to just be helpful, but we realized that when we humbled ourselves and actually asked for what we needed, the very people who we were in relationship with leaned into that relationship. And they were like, ‘Thank you so much for asking. We didn’t know you needed money. We kind of just thought that you were a rich church and wanted to do stuff for us. So if you’re actually not a rich church and the building is crumbling, then yes, let us help you.’”

More at St. Mark’s

At St. Mark’s Episcopal Church, this same spirit has led to hosting five nonprofits, creating “a wonderful sort of synergistic, creative, active space in our community at all times,” Witchger said.

Two of the programs she addressed specifically began in the winter of 2024. “We saw a huge influx of New Yorkers in the East Village (who were) being bussed in from Texas and Arizona and other places into the city. And we responded to a call from local elected officials asking faith communities to open their doors for warming. So to be warming centers for folks who were spending long days outside because they were residents at New York City shelters at night but didn’t have places to go during the day.”

The first day the warming center opened, 100 people came to seek shelter. Most were West African men.

“If you’ve made it to St. Mark’s, you’ve arrived. You are welcome here. There’s a place for you here, you belong.”

“As we began to listen to the stories, the journey many of these men had, we heard stories of going from one place to another and not finding home, not finding belonging. … And as we heard these stories over and over again, we realized what we wanted to be was a place where we could say, ‘If you’ve made it to St. Mark’s, you’ve arrived. You are welcome here. There’s a place for you here, you belong.’”

With that new understanding, the church changed the name of its ministry from being a “warming center” to being a “welcome center.”

That ministry then led to another ministry that offers residential housing at another location, “using principles of welcome and belonging.”

St. Mark’s Church is one of the oldest faith communities in the city, founded in the 1640s.

As moderator of the panel, Aikin said the primary issue churches face in considering new ministries is space. “More than anything, space is what allows community to happen. It’s not only where we need, it’s how we need and connected among community.”

How space is used is a factor separating “the 75% of congregations that will still be here in five years and the 25% that won’t. The more connected we are to our communities and to each other, the better our chances that we thrive.”