Agustín Pérez began selling fruits in the Bronx two years ago. In that short time period, the New York City Department of Sanitation (DSNY) and the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation (NYC Parks) have confiscated his goods six different times because he did not have a permit or a license to sell on the street. The losses cost him roughly $10,000.

“They took my strawberries, oranges, mandarins, tables, everything—even the trash,” said Pérez, who sells in the Parkchester neighborhood.

Vendors selling food must obtain permits through the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (NYC Health).

“The city council passed the LL18 of 2001 that changed how street food vendors can get a permit. Supervisory licenses are offered [by the DOH] to people on waiting lists that were created in 2022,” explained NYC Health spokesperson Shari S. Logan.

Those selling merchandise must apply through the Department of Consumer and Worker Protection. Unlicensed street vendors such as Pérez are frequently fined by the New York Police Department, even though the city hasn’t accepted new applications for its general vending license waitlist since 2016. In 2024, only 127 new permits were granted, according to ABC News. Fines for working unlicensed can reach up to $1,000.

This past summer, conditions for vendors came to a boiling point, as Mayor Eric Adams cracked down on local vendors and vetoed efforts his administration once claimed it wanted to pursue to make street vending safer for locals and more accessible for vendors. Adams worked overtime to ensure that, instead of receiving a fine for civil offenses, those found vending unlawfully could be charged criminally, requiring a court hearing. Under the Trump administration, Adams’ efforts could trigger immigration consequences for thousands of the city’s undocumented vendors.

“It makes undocumented vendors in particular extremely vulnerable to the increased enforcement efforts through the federal administration with the support of our mayor,” said Shamier Settle, a senior policy analyst at the research think tank the Immigration Research Initiative. “It’s not just undocumented vendors, because this administration has made a point of not only targeting people who they’re going after, but anybody else who they come across.”

Even before the Adams and Trump administrations, street vendors in New York City have long faced threats from city agencies—and these aren’t the only serious problems that plague the more than 23,000 street vendors in the city, an estimated 20,000 of whom are currently on the waitlist for permits.

The vendor community itself is fragmented.

This was evident when they rallied in support of a recent street vending bill. While members of various street vendors organizations were present to support the same cause, they stood on opposite sides and aligned themselves with different advocacy groups, often depending on their borough.

All are fighting for vendors’ rights, but disagreements persist over how to approach the struggle.

Widening divides

A 2024 study from the Immigration Research Initiative found that 96% of street vendors are immigrants and, among general merchandise street vendors, 13% are undocumented. In the case of food vendors, the number of undocumented immigrants rises to 27%. The largest percentages of food vendors come from Mexico, Ecuador, and Egypt, with general merchandise vendors coming from Senegal, Mexico, and Ecuador.

For unlicensed street vendors, the main challenge is to avoid being fined by authorities such as DSNY, NYPD, and NYC Parks. But even licensed vendors face challenges, such as being ticketed for leaving trash in their area or, more broadly, the looming threat for undocumented vendors that any interaction with law enforcement may lead to immigration consequences. Before September, a fine from local authorities translated into a criminal charge, which could result in deportation.

Adding to these problems is the fear of persecution, in large part due to Trump’s anti-immigrant political rhetoric and nationwide raids by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). In Manhattan’s Chinatown this week, ICE targeted street vendors in a raid. Despite its designation as a sanctuary city, half of the immigration arrests inside courts have also taken place in NYC, causing a chilling effect for the undocumented street vendors who must attend proceedings in these same courtrooms. Ramping up their fears, Adams has repeatedly attempted to collaborate with the Trump administration to widen the scope of ICE’s power in NYC. Adams himself has also gone out of his way to target immigrant vendors.

Before June 2023, there were approximately 90 vendor stands operating in Corona Plaza, the heart of the Corona neighborhood in Queens. The mostly immigrant vendors who made up the informal marketplace sold an array of foods from across the world, including empanadas, kabobs, arepas, and tamales.

After complaints regarding trash and traffic, in July 2023, the DSNY and the Department of Transportation (NYC DOT) made an agreement with the vendors that if they kept the area clean and the nearby streets accessible, they could continue operating. According to city officials, the vendors failed to meet those commitments.

“The Department of Transportation told us that if we really wanted a market to operate within Corona Plaza, we first had to constitute as an association. That’s how I got involved, because no one else wanted to take on the task of inviting our fellow vendors to form that association,” said Rosario Troncoso, a vendor and leader of the Asociación de Vendedores Ambulantes de Corona Plaza (AVA), an offshoot of the nonprofit advocacy organization the Street Vendor Project (SVP).

The DSNY and NYC DOT came to the plaza to inspect compliance in late July.

“They tried to show vendors what they were doing wrong, but many didn’t listen,” Troncoso said.

Rosario Troncoso is a street vendor who sells merchandise in Corona Plaza, Queens, and led the legalization of the Asociación de Vendedores Ambulantes de Corona Plaza. Credit: Ana María Betancourt

Rosario Troncoso is a street vendor who sells merchandise in Corona Plaza, Queens, and led the legalization of the Asociación de Vendedores Ambulantes de Corona Plaza. Credit: Ana María Betancourt

On July 27, around dawn, the DSNY cleared the plaza. “They said it was chaos—food everywhere, and you couldn’t walk,” recalled Troncoso.

To bring back the market, vendors staged a four-month sit-in, demanding the right to work. The protest ended in November 2023 after negotiations between vendors, city agencies, elected officials, SVP, and AVA.

During the negotiations, the cracks in the Corona Plaza street vendor community began to show. The resolution granted 14 vendors temporary licenses for four months, with the option to renew. Seven licenses were for food sellers and seven for merchandise vendors. At the beginning, dozens of vendors were in support of these conversations. However, as it became clear just how few vendors would have the opportunity to lawfully return to the plaza, many left to sell elsewhere. For participating in negotiations, Troncoso received harassment from fellow vendors both online and in person.

“They filmed me, shouted at me. On Facebook, they threatened to beat or kill me,” she said.

NYC DOT and the Queens Economic Development Corporation (QEDC) were tasked with overseeing vendors’ compliance in Corona Plaza.

“The public can still use the space while street vendors can still use it, so more types of members of the community can use it at the same time. And I think that it’s better for everybody, and it’s a symbiotic relationship, because now the public can come here. They can patronize us if they want to,” said Suny Hendre, QEDC’s manager of Corona Plaza.

By 2024, some Bronx-based vendors split from SVP to form yet another affiliation. They called it Bronx Street Vendors (BSV), citing a lack of representation. According to Bronx vendors, they were never given the opportunity to discuss their insights on the Street Vendor Reform Package with the City Council.

“What we want to propose is the opportunity to sit at the table where these agreements are reached with the authorities to take us into account, because we are being underestimated. We are spokespersons for our fellow workers, and we have countless significant projects addressing informal commerce,” said Vicente Veintimilla, founder of BSV.

Members in the Bronx hoped to be permitted by 2025 and wanted the decision-making of the Street Vendor Reform Package in the City Council to happen this year. Some of the members asked SVP to speed up the City Council process. SVP told Prism that while they are aware of the urgency of the reform package, they can only pressure lawmakers—not pass laws.

Erratic enforcement

During his time in office, Adams has taken an aggressive approach with the street vendor community. In April 2023, he issued an executive order authorizing DSNY to fine street vendors.

“Mayor Adams designated DSNY as the lead agency on street vendor enforcement. Prior to that date, the Department of Consumer and Worker Protection (DCWP) handled street vendor enforcement,” explained DSNY spokesperson, Vincent Gragnani.

In November 2024, New Yorkers voted to support the DSNY’s ability to fine street vendors in city law through Ballot Proposal 2, which increased DSNY authority to hold street vendors accountable if they didn’t follow rules on city properties.

Gragnani told Prism that the agency’s enforcement focuses on “situations where vending has created dirty conditions, safety issues, items being left out overnight, and setups that block curbs, subway entrances, bus stops, sidewalks, or store entrances.”

But vendors say the enforcement is erratic.

“Sanitation doesn’t check who’s breaking the rules,” Veintimilla said. “They show up, and whoever they catch, they catch.”

According to NYPD data analyzed by the local publication City Limits, in 2024 sanitation issued 4,144 tickets and confiscated 4,323 vendor items. Despite DSNY’s expanded enforcement role, that same year, the NYPD issued the most vending tickets, 9,376—and more than twice as many as the 4,213 issued in 2023. In the first two quarters of 2025, the NYPD issued 867 tickets.

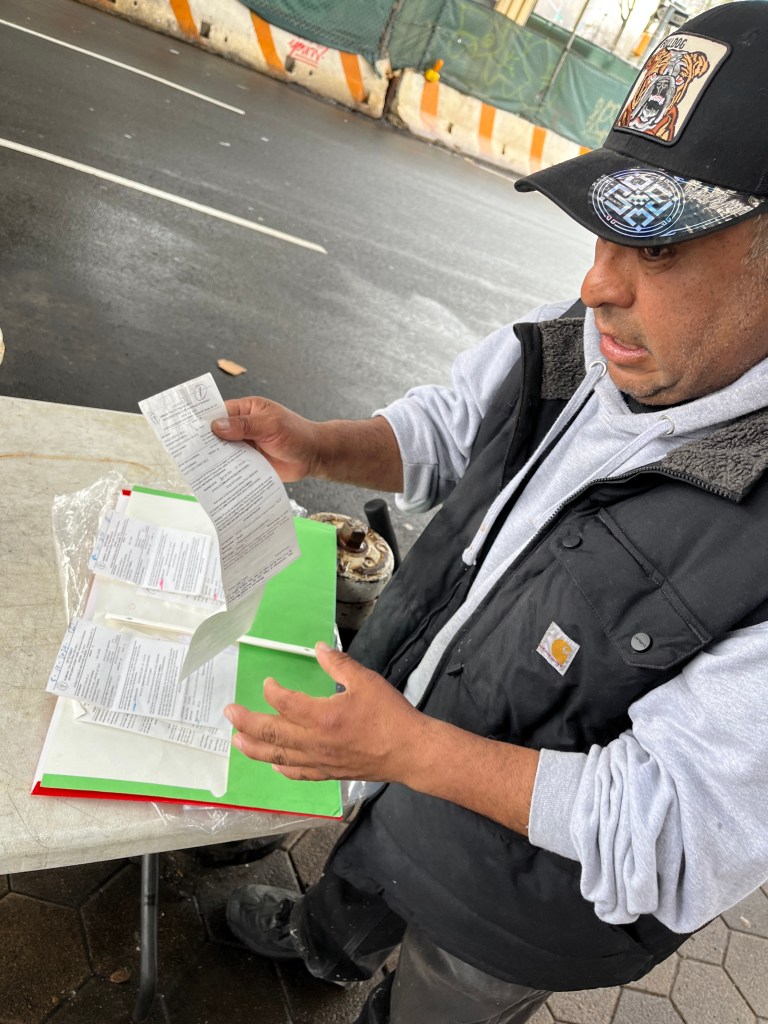

Miguel Varela goes through a folder of all the fines the New York City authorities have given him. Credit: Ana María Betancourt

Miguel Varela goes through a folder of all the fines the New York City authorities have given him. Credit: Ana María Betancourt

Vendors say the fines are financially devastating, and it’s impossible for them to pay such large sums of money. According to the Immigration Research Initiative study, food vendors’ incomes are usually between $250 and $1,000 per week BSV member Miguel Varela, a merchandise vendor originally from Mexico, has been bombarded by a series of debilitating fines.

“The NYPD gave me eight tickets during the last two years. Some of them are over $7,000. It’s hard to support my family like this,” Varela said.

The other agency with the power to ticket street vendors is NYC Parks. Vendors ticketed by the agency are often accused of being unlicensed and selling in city parks, interfering with park use, or operating grills in the parks.

For two decades, Marlene Ensaldo supported her family by selling fruit from a public park in the Parkchester neighborhood of the Bronx. That changed in 2023, when she received three $1,000 fines from NYC Parks for selling without a license. Now she sells just outside of a subway station to avoid further penalties.

“I applied for the license years ago, but never got an answer. Now I don’t even know where to go to avoid tickets,” said Ensaldo, a vendor, SVP leader, and BSV organizer.

NYC Parks told Prism that enforcement begins with education.

“We collaborate with NYPD to ensure that park rules are observed and enforced. Our first course of action is to educate the public on our rules and regulations. If not followed, the next step would be to issue a summons,” said NYC Parks spokesperson Kelsey Jean-Baptiste.

SVP knew that its members were tired of having their livelihoods threatened by what often seemed like arbitrary enforcement, so the organization partnered with a powerful resident to try to reform local laws.

“Not going to happen overnight”

Bronx Councilmember Pierina Sánchez has a history of going to bat for street vendors. In 2018, she worked as a labor adviser for former Mayor Bill de Blasio, and they co-authored Intro 1116, a bill that passed in 2021 and called for issuing 4,000 new street vending permits over 10 years. This bill was enacted as Local Law 18 on Feb. 28, 2021, when Sánchez was elected as a councilmember.

The law, which went into effect in July 2022, mandated the city to issue 445 new supervisory licenses for food vendors annually over 10 years. The supervisory license is a necessary step before vendors can qualify for a full permit. However, the city failed to meet its own targets when it came to supervisory licenses. According to the Comptroller’s Office, only four vendors received new permits between March and May 2023. ABC News reported that just 127 were issued in all of 2024.

“There are many street vendors who will come to me and say, ‘You need to move this bill now.’ My response is I’m one of 51 [councilmembers], and we have to work by building the numbers. … We have to be strategic and tactical. The last reform for street vendors took 10 years. This one is not going to happen overnight as well,” Sánchez said.

In 2024, following the approval of Local Law 18, Sánchez and SVP introduced the Street Vendor Reform Package during the new legislative session. The package consists of four proposed laws: Intro 0431 aims to guarantee access to licenses and permits for street vendors without caps on permits. Intro 0408 focuses on creating a division within the Department of Small Business Services to assist street vendors. Intro 0047 aims to decriminalize street vending, while Intro 0024 defines where vendors are legally permitted to set up on city streets.

The bills received public hearings and in June, Intro 0047 passed in the City Council. However, on July 30, Adams vetoed Intro 0047, arguing that it was a matter of “quality of life” for New Yorkers.

“What is really disappointing [is] to see him flip against one of his own recommendations,” said SVP Managing Director Mohamed Attia. “Something that his administration has advocated for and actually recommended to the city government to do. This just signals to us and to all New Yorkers that now the mayor is really playing politics, and he’s using our people.”

City council members voted again on Sept. 10 and overrode the mayor’s veto, with two-thirds supporting the bill, which means that street vending without a permit or license can no longer lead to a criminal penalty. Now considered a civil offense, unlicensed vendors can pay a fine if they’re cited.

Intro 0431 will lead to 100 new street vending permits in 2026. As part of these efforts, the city’s street vendor advisory board, a multiagency and multi-stakeholder effort, must provide recommendations, help monitor rollouts, and advise on regulations.

“Once we override [Intro 0047], it will take 180 days, or six months, to take effect. The legislation the mayor supported, and his own NYPD and city agencies supported, has now been delayed by another more than six months because of his veto,” explained NYC Councilmember Shekar Krishnan, who sponsored Intro 0047.

Some street vendors are relieved with the news.

“Six months is a win for us. The most important thing for us is that they stop bothering us and let us sell. Six months is winter, so we’re expecting that next summer we’ll be fine,” said Ensaldo.

Other vendors view the bill differently. Its passage hasn’t been without controversy in the street vendor community, in large part because it prioritizes applicants based on whether they have held licenses continuously since 2017 and whether they’re already on the city’s waitlist for a license. Veintimilla of BSV told Prism that the order should instead favor those who have been active in grassroots organizing, followed by full-time vendors, then part-time vendors, and finally newcomers to the field.

“That’s what we call meritocracy,” Veintimilla said. “It’s about community involvement, marching, participation. Just buying and selling doesn’t make you a vendor.”

Veintimilla and many other BSV members no longer feel represented by SVP’s reform agenda, even though they were tapped for input when the bill was crafted. “We’re a democracy,” said SVP Deputy Director Carina Kaufman-Gutierrez. “Vicente was also a part of that voting and also proposed these ideas, and so if he doesn’t like it now, that’s OK. Everybody is welcome to change their minds, right? But let’s not forget the past.”

In the meantime, the remaining bills in the Street Vendor Reform Package are awaiting a decision, keeping thousands of NYC vendors in limbo, caught between enforcement, criminalization, delayed legalization, and internal division.

Editorial Team:

Tina Vasquez, Lead Editor

Carolyn Copeland, Top Editor

Rashmee Kumar, Copy Editor

Related