The Champlain Valley once served as a major source for the material with which pencils make their marks on paper— graphite.

There’s no exact date for the discovery of graphite in the region. Likely native populations found some and used it to mark on various mediums. There are stories of area farmers finding black smears in snow, then tracing them to further deposits on the ground.

I found one reference to graphite in Ticonderoga and environs as early as 1815. Yale University mineralogist Benjamin Silliman saw samples of what he labeled ‘plumbago’ when traveling the southern Champlain Valley in 1822. For a long time, that was the term widely applied to the carbon-based mineral. Only in 1789, the same year George Washington was inaugurated as the first president, was the name “graphite” used. It derived, appropriately, from the Latin verb meaning “to write.”

Multiple sources reference discovery of such deposits at a spot now known as Lead Hill in the tiny hamlet of Chilson. In fact, much of the area around Ticonderoga turned out to be rich in graphite. Mines began extracting the black mineral, and mills were built to process it. Modest efforts at graphite refining began locally as early as 1832. Eventually, American Graphite Company consolidated most of the small operations under its aegis.

By 1863, American Graphite Company not only ran mines, but had also established a significant manufacturing presence along the Lachute River in Ticonderoga. Its new processing facility opened that year. In one way or another, graphite processing in Ticonderoga would continue over a century, until the late 1960s.

The old graphite mine shafts are still open. Photo provided by Rich Frost.

The old graphite mine shafts are still open. Photo provided by Rich Frost.

Today we think of graphite primarily for its use in pencils. Indeed, the substance was found to be an effective marker centuries ago; shepherds would mark their flocks with it. However, before the Civil War, other uses ranked higher in importance. When finely powdered, it was an effective lubricant; this function continues to be commercially significant. It also found its way into gunpowder, and later, into paints.

Along with its marking qualities, graphite boasts the ability to withstand high temperatures. This made it usable in stove polish. With the growth of American industry, graphite also became important in making crucibles integral to the production of steel.

The manufacturing of crucibles fueled the growth of the Joseph Dixon Crucible Company, the world’s largest graphite concern. Dixon bought out American Graphite in 1873. Although Dixon pioneered mass production of pencils, pencil lead was only one of the company’s main products. Dixon stove polish was equally in demand, as were those crucibles that gave the name to Dixon’s enterprise.

Let’s spotlight Mr. Dixon. As a boy in his native Marblehead, Massachusetts, Joseph Dixon (1799-1869) noticed that merchant ships arriving at the docks often dumped graphite taken on as ballast in faraway Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). Rather than see the mineral go to waste, Dixon began exploring ideas for using the substance.

Graphite, mistakenly called lead by early chemists, had been discovered in England as early as the 1500s. Pure graphite crumbled easily, but some experimenter found that combined with clay, it made a good material for pencil lead. That simple formula remains the standard today.

British companies took the lead in producing lead (notice the use of heteronyms!) pencils. Italian craftsmen added the idea of sheathing them with wood. The classic hexagonal shape was an American addition.

Seeking his own system for making pencils, Dixon partnered with a cabinetmaker (whose daughter he later married) and went into business. Quill pens dominated that era. Though by 1829 he could manufacture pencils to sell for ten cents, Dixon found a scarcity of takers.

Fortunately, continued profits from stove polish, crucibles and other output from the Joseph Dixon Crucible Company proved sufficient to support his quest for a more practical pencil. An inveterate tinkerer who also toyed with camera viewfinders and devised counterfeit-proof bank notes, Dixon continued working on better manufacturing strategies. Meanwhile Dixon Crucible bought out American Graphic holdings in Ticonderoga, adopting the location name for a line of pencils.

As so often happens in history, war sped technological change. The convenience of pencils over liquid ink quills became established during the Civil War. By the end of that conflict, Dixon had devised machines capable of producing 132 pencils a minute. Within three years after his death in 1869, the output at his New Jersey plant exceeded 86,000 a day.

From the 1880s through the beginning of the twentieth century, New York State ranked second in the world for graphite production. Almost all that graphite came from the Adirondacks, most of it from a belt extending along the southern end of Lake Champlain and the northernmost aspects of Lake George. Far and away the largest contribution came from newly developed Dixon operations in a village called Graphite.

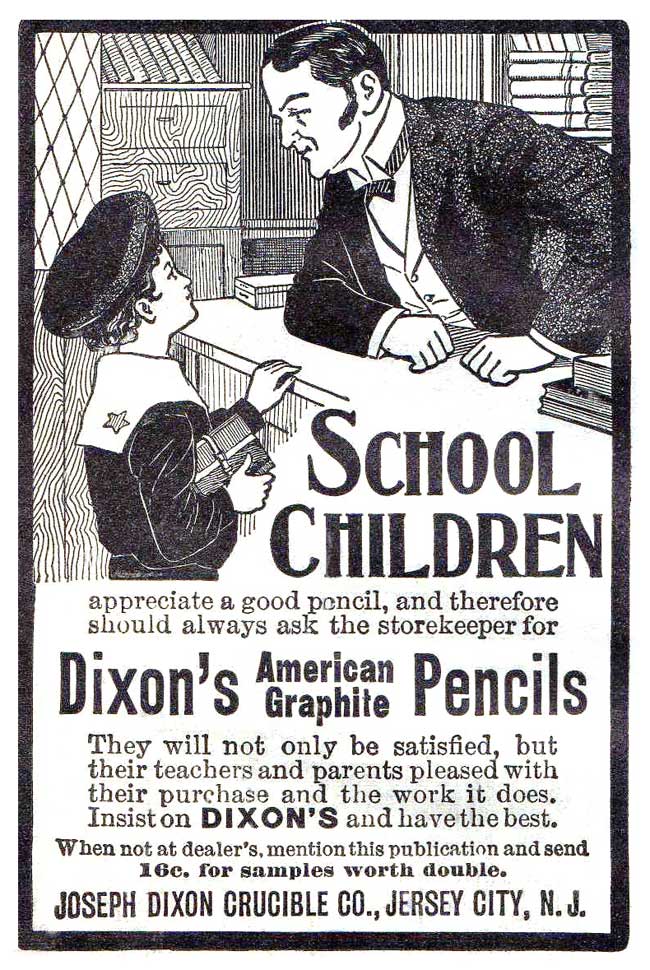

A poster advertises Dixon’s graphite pencils. Photo provided by Rich Frost.

A poster advertises Dixon’s graphite pencils. Photo provided by Rich Frost.

A man named Samuel Ackerman discovered graphite in the 1880s near the village of Hague on Lake George. He had been skidding logs over exposed bedrock and noticed a greasy residue. Efforts were begun to exploit a lakeshore site, but water kept flooding the works. In 1887, a much larger supply was found a few miles west of Hague. This would eventually become the largest graphite mine in the U.S., and one of the biggest on the planet.

The company built a full-fledged town to be known as – surprise! – Graphite. Homes were built, plus boarding houses for both single men and families. In time, there was a blacksmith shop, sawmill, horse barn and livery stable, a powder magazine to store blasting material and a “hose-house” to combat the ever-present risk of fires.

As the population grew, a post office and stores were established. A two-room school boasted enrollments. Naturally a few saloons sprung up along the way, plus a bowling alley and a dance pavilion called Echo Mountain Social Hall. One blog mentioned a nearby brothel. The mine recruited from its 150 workers to field a baseball team. Both miners and family members joined casts for amateur theater productions.

Population grew to 400, necessitating construction of another boarding house (called the Hotel Graphite) in 1890 along with more homes and cottages, and another store. Graphite had its own community news section in local newspapers.

The graphite mine itself included a surface pit that was 600 feet long, plus underground works that went down 200 feet. At first, the material was transported to Ticonderoga for processing. However, with growth in output, the company decided to build a mill right at Graphite. By 1889, trams had begun carrying ore to the new crushing plant for preliminary processing

When the mill burned down after only a year of use, it was quickly replaced. According to the Sept. 18, 1890 Essex County Republican, the village now boasted the “largest and best equipped mill in the United States for the separating and concentrating of graphite.” “Under the excellent management of Mr. Geo H. Hooper,” the new three-story factory boasted steam heat, electric lights and an automatic feed to the crusher and stamper.

Horses and wagons, later replaced by trucks (Pierce-Arrows, apparently), transported the graphite to storage silos in Hague. From there, boats carried it north on Lake George, then overland to Ticonderoga for final processing. During winter, horses would instead haul the graphite in sleds across the frozen water.

Output from Graphite exceeded 2 million pounds annually by 1912. This sounds impressive, but it was a fraction of that mined in such far away places as Ceylon and Madagascar. World-wide surplus (globalized economic issues are not new!) forced prices down, and profits dropped. The mine closed precipitously in 1921.

Meanwhile, American/Dixon’s main factory in Ticonderoga was quickly rebuilt after a fire. The mill refined locally sourced graphite until 1921. When the operation in Graphite closed in 1921, the plant began relying on imported ore.

Another fire in 1968 led to the demise of graphite processing in Ticonderoga. As reported by Plattsburgh’s Press-Republican on Jan. 10, 1968, the blaze apparently resulted from friction-induced heat from a jammed conveyor belt. Temperatures near 30 below zero hampered fire fighters, and the wooden three-story factory was a total loss. Fortunately, no one was injured.

The economic loss was estimated as $1 million. Although the industry had thrived 105 years in that location, the Dixon Company chose not to rebuild locally, instead opting for a new plant near its other facilities in New Jersey. The enterprise donated the land to the village and left the region completely. The firm itself, after several mergers, still remains in operation as the Dixon Ticonderoga Company. Its signature Dixon Ticonderoga pencil thrives as one of America’s most long-lived brand names.

Years ago I wandered the former village. By chance, a past employee happened to be there. He guided me past a few foundations and brought the operation to life, pointing out locations of a boarding house, the paymaster’s office and a dance hall. He also showed me some open shafts. The serendipitous presence of a guide prevented me from falling into one of the unprotected shafts!

Remnants of the region’s graphite enterprises are few. Forest regrowth has obscured those shafts and building foundations. Most of the one-time hamlet lies within the Joseph Dixon Memorial Forest, dedicated in 1958. I have long thought there might be an opportunity to add trails and markers and make this into an interesting interpretive site.

There’s an unusual post-script to the Graphite village story. After the mine closed in 1921, huge bat colonies established themselves within the man-made caverns. The Nature Conservancy became active in campaigns to protect these nocturnal flying mammals.

Unfortunately, these bat colonies were later devastated by the disease commonly known as white nose syndrome. I’m not aware of the current status.

Until recent announcement of a new mine near Governeur, graphite production in the Adirondacks has been merely an interesting piece of history. But sometime look at your child’s (or your own) yellow pencil and see if it boasts the name Dixon Ticonderoga on its shaft. Remember that graphite for those pencils initially came from the Champlain Valley, from the Dixon mines near Ticonderoga and Hague.

This was adapted from a prior column in Lake Champlain Weekly, and from a chapter in Richard Frost’s book “Rich in History: A Champlain Valley Reader.”

Sign up for our free newsletters