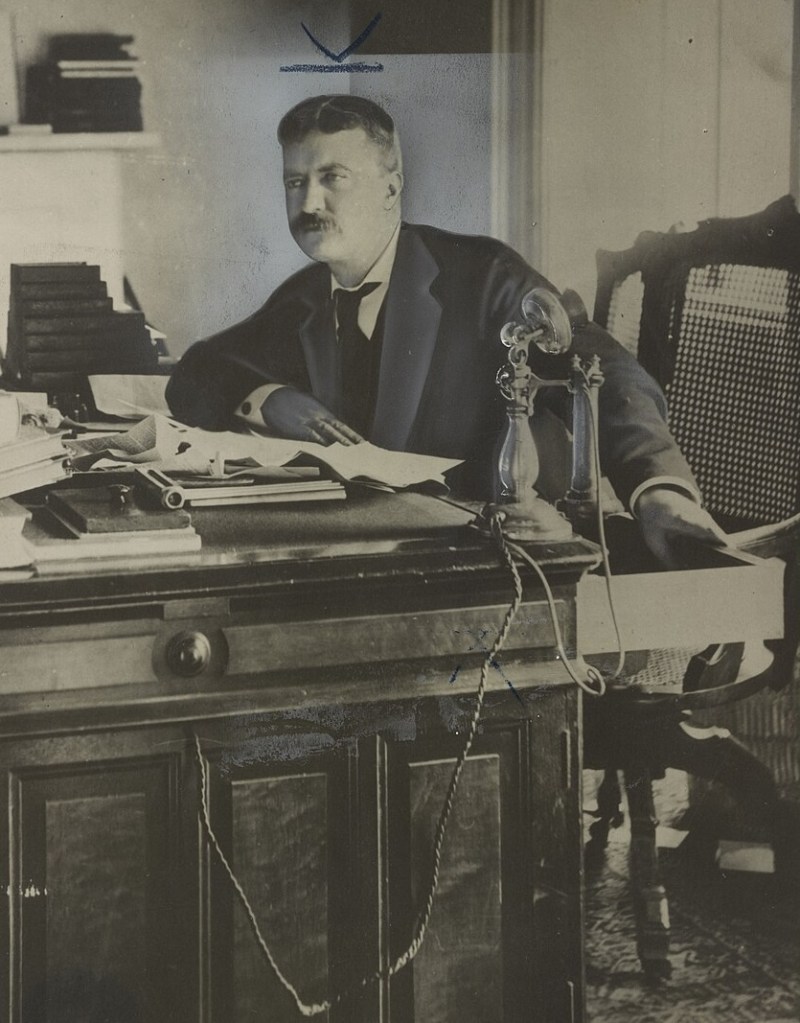

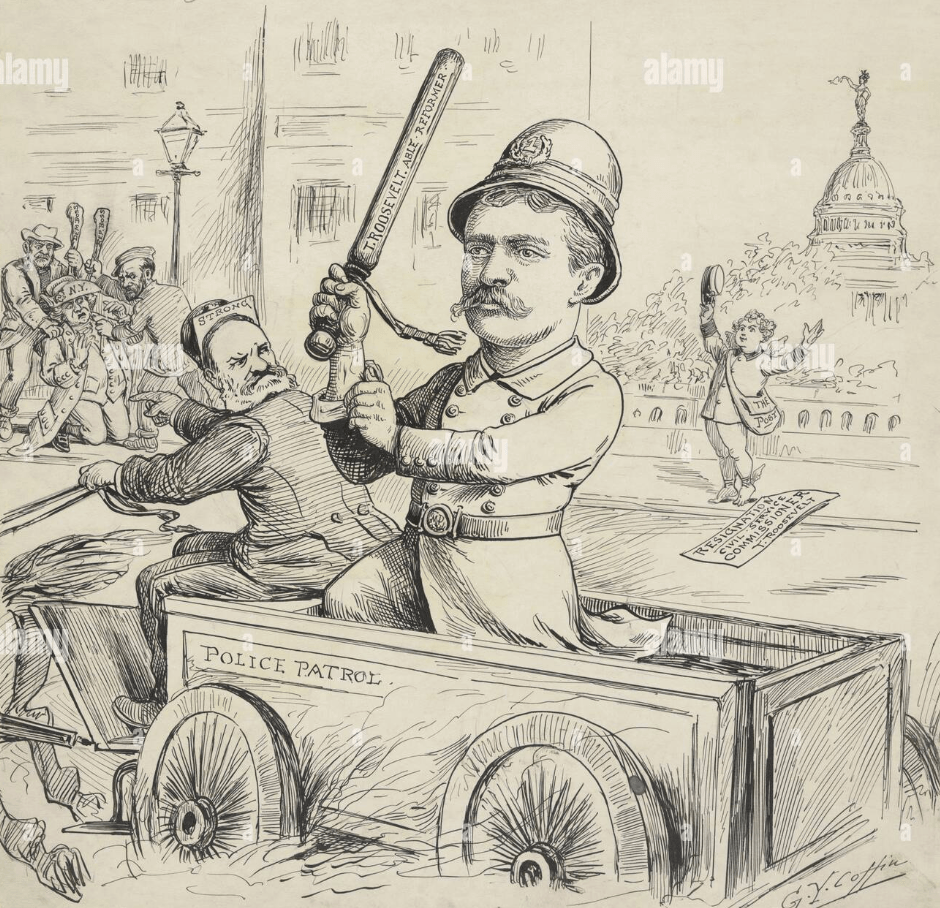

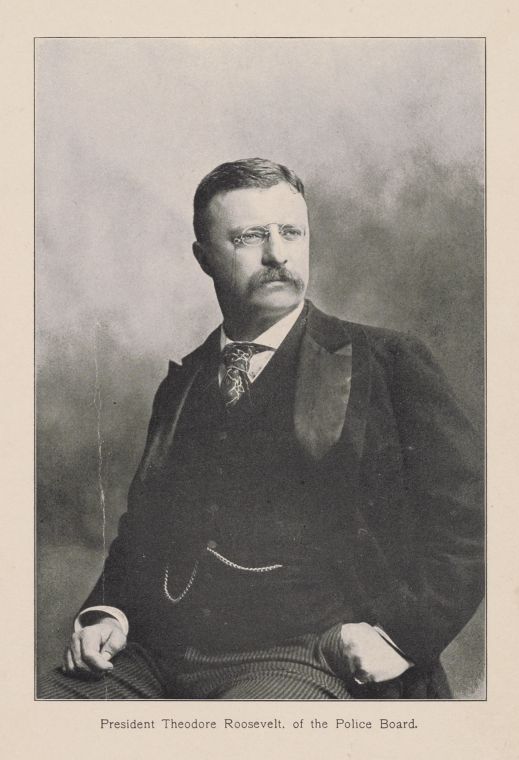

In 1895, Theodore Roosevelt was tapped to be one of four commissioners in charge of New York City’s police department. He quickly got to work professionalizing a force long mired in scandal.

Some of his new rules focused on hiring better cops. This future American president called for physical and mental exams for all recruits; no longer could a political connection land a man a job as a patrolman, Roosevelt recounted in his 1913 autobiography. He also awarded medals and promotions to officers who performed their duties valiantly.

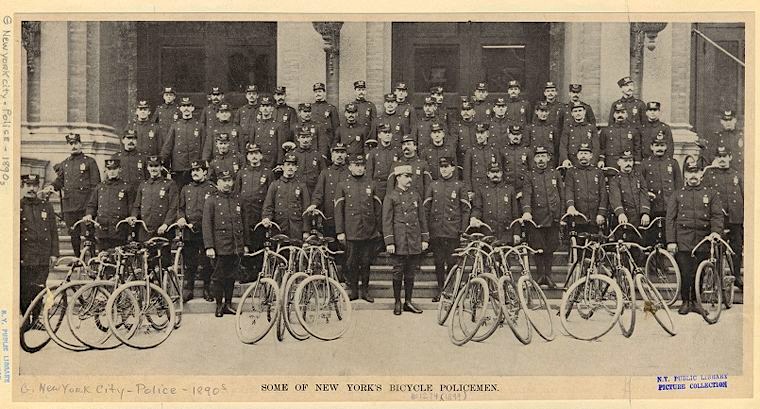

Other changes involved utilizing new technology. He mandated pistol training, set up call boxes on city streets that connected to telephones in precinct houses, and launched a bicycle force, aka the “scorcher squad.”

Roosevelt also ended the longstanding practice of sheltering the homeless in station house basements on cold nights.

All of these reforms came about after the Lexow Commission of the early 1890s exposed widespread bribery on the part of the Tammany Hall–controlled police. Mayor William Strong, who sailed into office on an anti-Tammany ticket, brought in Roosevelt to repair public trust.

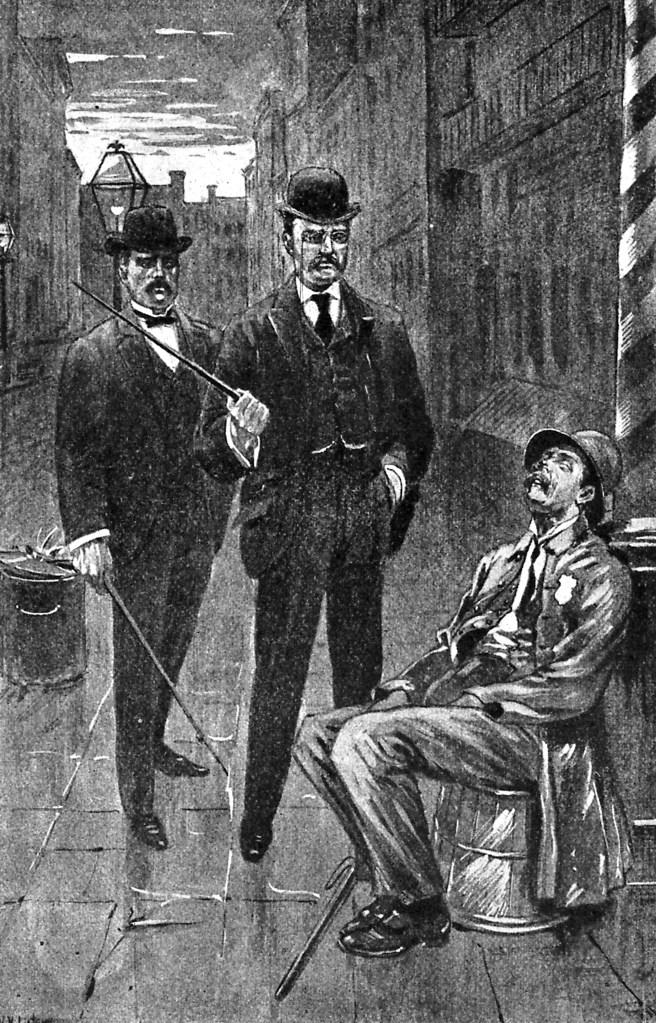

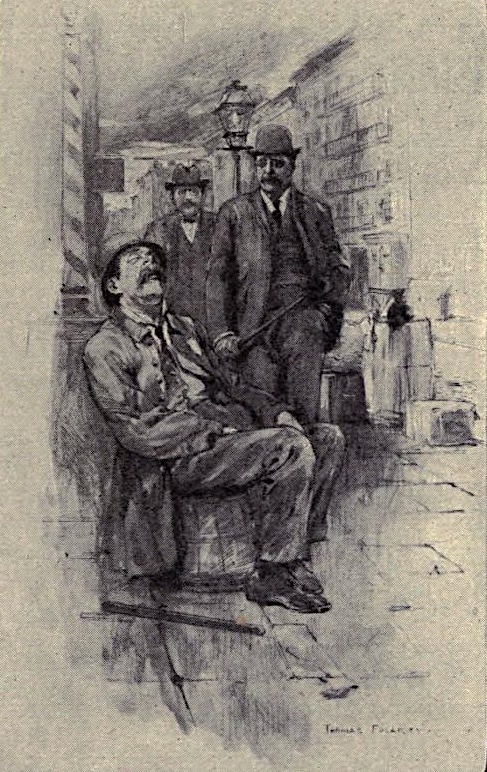

But Roosevelt didn’t simply issue new rules from his office at police headquarters on Mulberry Street. He hit the streets and went on patrols of his own, embarking on regular “midnight rambles” around Manhattan to catch lazy, corrupt, or unqualified policemen.

Roosevelt’s midnight rambles were chronicled by the city’s newspapers. The New York Times trailed him one June night in 1895 as he walked through an East Side precinct bounded by 42nd Street to 27th Street and Park Avenue to the East River.

“Police caught napping,” the headline read. In disguise, Roosevelt encountered patrolmen lounging in doorways rather than keeping an eye on the street. One cop was spotted in a coffeehouse indulging in an early breakfast. Some street corners were empty of the officers assigned to patrol them.

“A tour of the Bowery was then made,” reported the Times. “Four policemen were found on the thoroughfare. Two were lounging on a saloon corner and one was found seated in a doorway.” The delinquent cops had to report to Roosevelt’s office the next morning, as they were guilty of “laxity in discipline.”

Later that month, Roosevelt took another police commissioner, Avery D. Andrews, on a different midnight ramble. Through the wee hours, the men walked through today’s East Village and the Lower East Side, then headed to the West Side and ended the night in the Tenderloin.

This trip was mostly without incident, except for the several West Side cops who were discovered napping, reported the New York Herald.

On many midnight rambles, Roosevelt was accompanied by his friend Jacob Riis, author of the How the Other Half Lives—an eye-opening 1890 book that highlighted the squalid conditions of New York City’s tenement slums.

“It is long since I have enjoyed anything so much as I did those patrol trips of ours on the ‘last tour’ between midnight and sunrise,” Riis recalled in his autobiography, The Making of an American.

“I laid out the route, covering ten or a dozen patrol posts, and we met at 2 a.m. on the steps of the Union League Club. . . . I shall never forget that first morning when we traveled for three hours along First and Second and Third Avenues, from 42nd Street to Bellevue, and found of ten patrolmen just one doing his work faithfully.”

“One was asleep on a butter tub in the middle of the sidewalk, snoring so that you could hear him across the street, and was inclined to be ‘sassy’ when aroused and told to go about his duty.”

With Roosevelt on patrol looking for deadbeat officers, the police got the message. “The whole force woke up as a result of that night’s work,” wrote Riis (at right), as patrolmen worried that “Mr. Roosevelt’s spectacles might come gleaming around the corner at any hour.”

Roosevelt was made president of the commissioners, but he left the job in 1897 with grander political ambitions under the new presidency of William McKinley.

His late-night trips through Manhattan established him as tough and vigorous, and he truly enjoyed them. “These midnight rambles are great fun,” he wrote in a letter to his sister Anna.

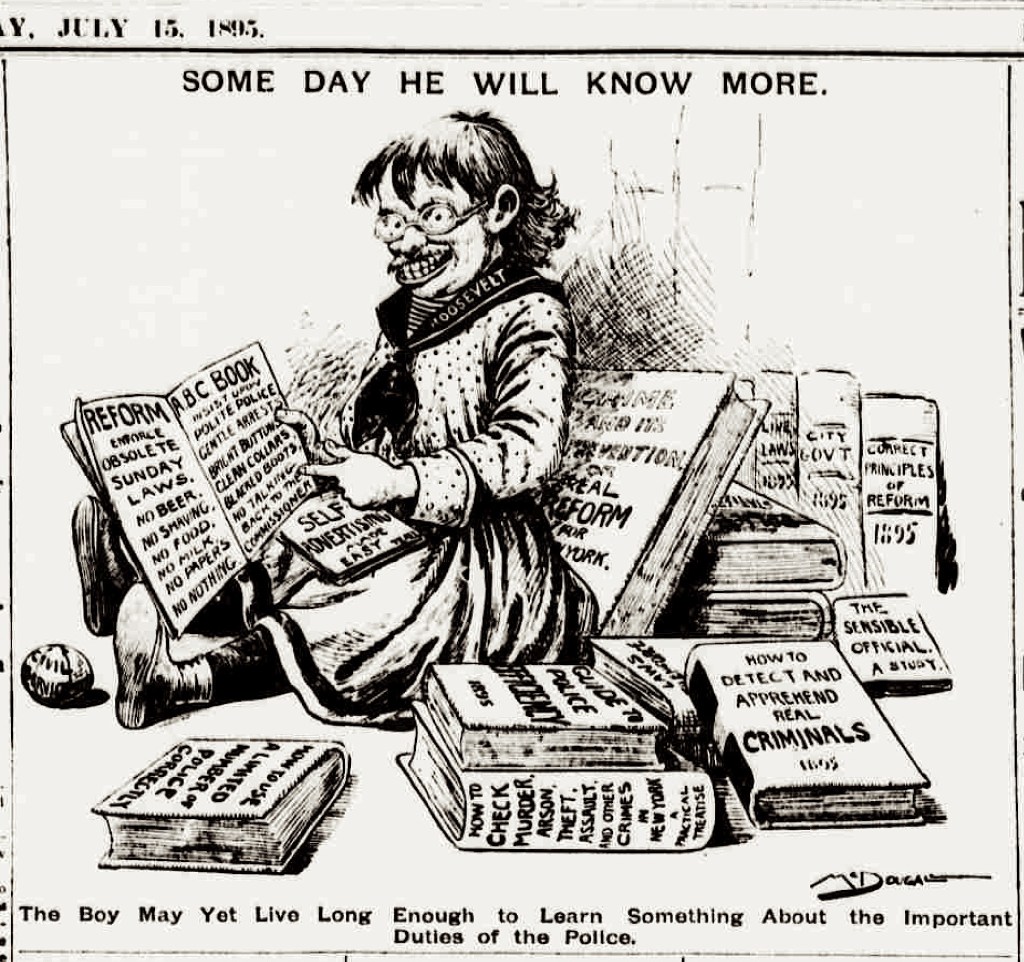

But his legacy as head of the New York police department is mixed. On one hand, the reforms he instituted helped give cynical New Yorkers more faith in a police force long considered hopelessly corrupt and inept.

But not everyone, particularly New York’s large German immigrant community, appreciated Roosevelt’s enforcement of the city’s long-ignored excise law, which shut down saloons on Sundays. And Tammany Hall politicians who governed by graft were glad to see him go.

His turn as commissioner did help Roosevelt achieve national office. “He earned a law-and-order reputation from what he did in New York,” said Richard Zacks, author of Island of Vice: Theodore Roosevelt’s Quest to Clean Up Sin-Loving New York, in a History.com article.

“And he played it up and congratulated himself in speeches about cleaning up the country’s most corrupt city.”

Curious about the backstory of the NYPD and how a corrupt force transitioned into a disciplined crime-fighting organization? Check out the latest episode of The Gilded Gentleman podcast, where Carl Raymond and Ephemeral New York discuss law and order in the gilded city. The episode drops on Tuesday, October 28!

[top image: MCNY, X2011.34.3773; second image: Wikipedia; third image: Alamy; fourth image: NYPL Digital Collections; fifth image: Alamy; sixth and seventh images: Wikipedia; eight image: via thirteen.org; ninth image: NYPL Digital Collections]