Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

In the waiting rooms outside the immigration courts at Manhattan’s 26 Federal Plaza, everyone whispers. There are signs everywhere telling visitors to be quiet and not to use cellphones, but everyone mostly ignores the latter instruction: Kids need to be entertained; relatives need to be updated. The cell service is terrible, though—the building is a blank warren of antiseptic hallways and worn-down maroon carpeting, which seems to dampen any kind of cell signal and simultaneously amplify everyone’s voice, which is part of the reason that most people try to whisper.

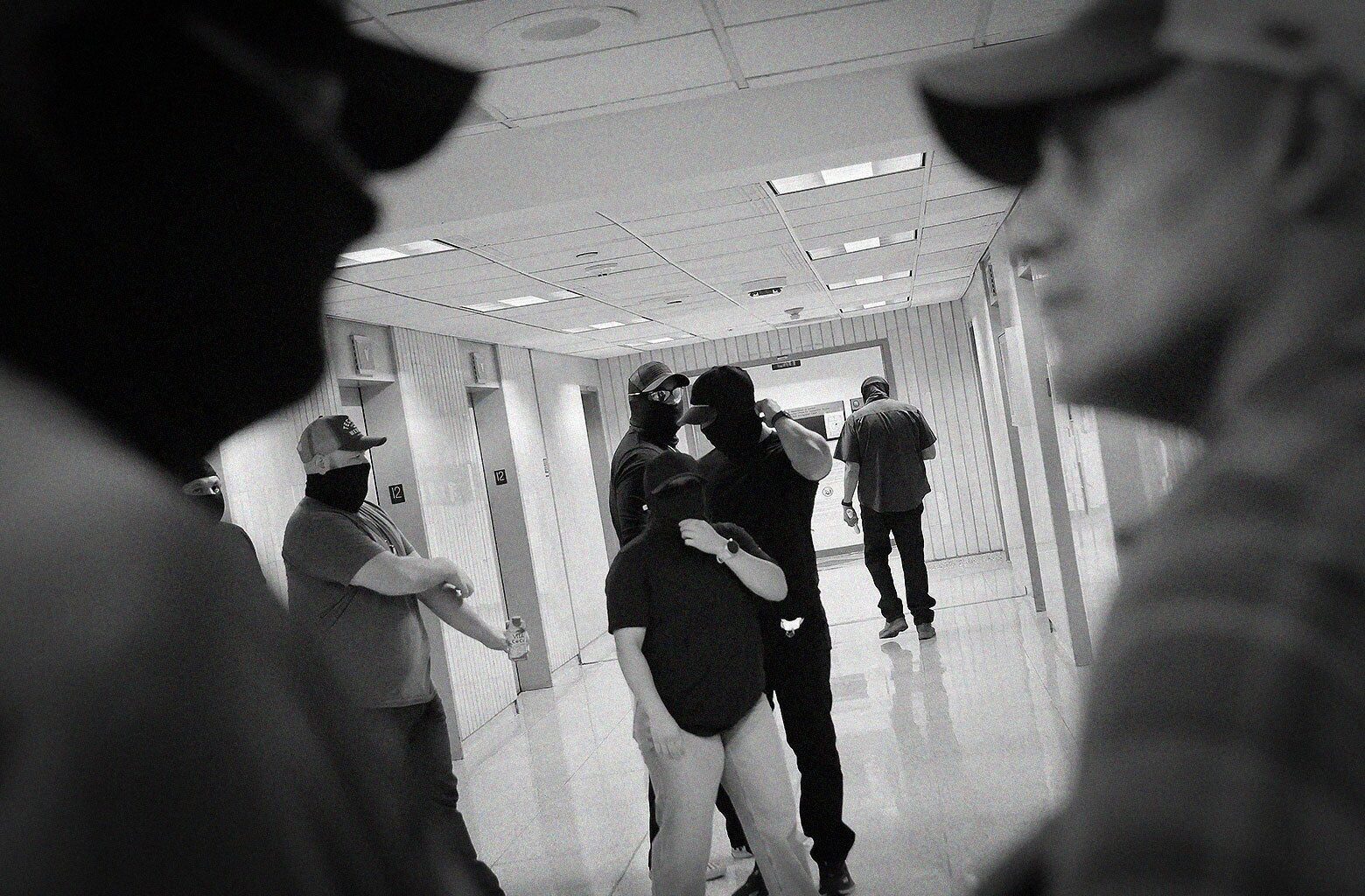

The other reason is that out in the hallway, just on the other side of an open door, there are masked men with guns who can make people disappear.

For months now, agents with the Department of Homeland Security’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement department have been arresting immigrants in the hallways of the Jacob K. Javits Federal Building, abruptly sweeping them from the slow churn of paperwork-based bureaucracy into cramped cells, confusing transfers and hastily chartered deportation flights. The building, which houses immigration courts on Floors 12 and 14, has become a flash point in Donald Trump’s brutal transformation of the United States’ immigration system, as armed and masked agents have abruptly arrested immigrants at various stages of the legal process. For immigrants, 26 Federal Plaza is a building that can make or break dreams. It hosts citizenship ceremonies and procedural court hearings that can reunite families or give an asylum-seeker a chance at a new life. But under Donald Trump, it also carries dire risk. On the 12th and 14th floors, gangs of masked ICE agents lurk. The 10th floor is filled with notoriously squalid cells. If an immigrant is summoned to 26 Federal’s courtrooms, there is no guarantee they will leave with their freedom.

None of this is apparent from the outside. Last week, as the federal government shutdown brought many services to a halt, I visited the immigration courtrooms inside 26 Federal Plaza to try to understand what the inside of Trump’s new immigration bureaucracy looks like. What I found was equal parts mundane and dystopian: hassled public servants, bored security guards, worried public observers, and stressed-out families all crammed next to disorganized gangs of federal agents, most of whom chose to cover their faces with balaclavas, hats, and mirrored sunglasses, their chests puffed out with body armor and tactical gear.

The hallways of 26 Fed are a perfect microcosm of the America that the president has promised to create. Trump began his political campaign in earnest in 2015 with a promise to build a wall between the U.S. and Mexico; this plan, though wildly impractical, was a clear mission statement for Trump’s vision of the country. Ten years later, his immigration policies have been sharpened from vague dreams of a wall into a system that hands the full weight of state power to a single arm of the government—the DHS—and gives it a blank check to intimidate, harass, arrest, and deport citizens and noncitizens alike who reside within the nation’s borders. That system has resulted in street protests outside facilities in Chicago, military deployments to cities run by Trump’s political adversaries, and aggressive propaganda campaigns aimed at demonizing immigrants and minority groups. But the everyday reality of the White House’s war on immigrants can be seen most in the quiet hallways of buildings like 26 Fed: paperwork filled out under the watchful eye of a secret police force that is allowed to act with impunity, breaking the social contract of laws and procedure in personal, invasive ways that dehumanize everyone it comes in contact with.

The carpet in the waiting area of one courtroom, for instance, is a drab maroon with a large stain in the corner. When I arrived, on Thursday morning last week, a toddler was adding to the mess, haphazardly scattering a package of Nacho Cheese Doritos onto a chair, as well as on the floor in front of him. His mother was clutching a stack of papers, glancing around the room the way that people do when they’re worried that they’re going to miss someone calling their name, like you would in the waiting room at the dentist, struggling to keep the chip debris to a minimum and largely giving up. A middle-aged woman pulled over a trash can and started to help pick up, smiling at the kid.

To get into the room, I showed my driver’s license to security guards outside, passed through a metal detector, and took the elevator up to the 12th floor. The floor was empty at first. There was no one waiting outside the elevators. I took a slow lap and, in a hallway on the northeast corner, walked abruptly into a gaggle of press photographers crowded around 10 ICE agents in masks.

The ICE guys all dress the same, a bizarre uniform that screams “cop” even without the gun belts and badges. They wear jeans or cargo pants, running shoes or boots, and either a button-up shirt or some kind of athletic-wear base layer, often Nike or Under Armour—the kind of bargain-bin sports apparel you’d see at a Nordstrom Rack. On their faces, they wear a stretchy fishing gaiter, usually topped with a hat, that almost completely obscures their faces. There are some variations on the theme: One had on a cowboy hat and boots, for instance, and just a few were sporting body armor. In my two days at 26 Fed, I saw only one federal officer who was not wearing a mask.

The court observers are not journalists. Some are lawyers; a few are priests. They come from a variety of organizations, from legal aid groups to Quaker societies, or are just concerned citizens who have realized they can show up and help.

The combined effect of this is both chilling and downright weird. Inside the building, the ICE agents aren’t responsible for internal security—that obligation falls to a private contractor called Paragon Systems, whose gray-uniformed guards often seem somewhat annoyed when the ICE guys show up on their floor—so they don’t say much. But it’s clear that they move freely around the building. At one point, a masked officer strolled into the waiting room, walked up to a young Latin American woman wearing a paper mask and a Lilo & Stitch hoodie, ordered her to remove her face covering, stuck his phone in her face, and took her photo. He then left, with no explanation. The woman didn’t say a word. Inside 26 Fed, ICE does whatever it wants. Everyone else—the staff, the judges, the private security, the lawyers, the press, and especially those caught in this system—can do nothing but watch it happen.

The only people opposing these agents, at least nominally, are court observers, public citizens who have taken it upon themselves to be present in the courtrooms and attempt to help, and sometimes physically escort, petitioners to and from their appointments. On busy days, a reporter told me, the building becomes especially chaotic. There are dozens of courtrooms spread across Floors 12 and 14, and observers and petitioners will bustle in and out, sidling past flocks of press and squads of federal officers. The observers are not journalists. Some are lawyers; a few are priests. Many do not speak Spanish, the most common language of the petitioners at the court, though several do. They come from a variety of organizations, from legal aid groups to Quaker societies, or are just concerned citizens who have realized they can show up and help.

But what they can do, unfortunately, is extremely limited. In the waiting room on Thursday morning, I sat down next to John, an observer from the Bronx who said he had been coming to the courthouse several times a week for the past month. (The observers spoke with me on the condition of anonymity, using pseudonyms to protect themselves.) He was explaining to another observer, a first-timer, how all this worked. “If they try to take someone I’m escorting, do you—do you, like, get in the way?” the first-timer asked, speaking softly. “Not unless you want to catch a federal charge,” John replied. “If they want to take someone, there’s nothing you can do.”

The whole endeavor is so futile it feels absurd at times. At one point in the late morning, the Paragon security guards came in and decided that the waiting room was too full. They cleared all the observers out and made them sit in a larger waiting room farther down the hall. The press and ICE agents crowded the walls outside. The court was still in session. The arrests usually happen after courts let out, so observers will typically try to make a connection with a client on their way in and tell them what to do when they get out: Head directly for the elevator, walking with a group if possible, and leave the building with all haste. Single men are particularly vulnerable. John told me that on one of his first days, he attempted to escort an Arabic-speaking man from his hearing to the elevator only to have him grabbed by ICE along the way. He never saw the man again. “Nothing about this is procedural,” John said. “These aren’t criminals. It’s absurd, wholesale cruelty.”

When ICE officers arrest an immigrant, they are often taken to the 10th floor, to holding cells that are not accessible to the public. These cells have historically been used to hold people for a few hours during processing; following the Trump administration’s blitz, they are used to keep dozens of detainees for as many as three days. Detainees sleep on bare tile floors, use toilets with no privacy, and are crammed into pens meant for a tenth of their number. In August, a federal judge ordered ICE to improve the state of the holding cells after several eyewitness testimonies cited overflowing toilets and other foul conditions, and a video emerged documenting dozens of men sleeping on the floor of a group cell. “Look how we are, like dogs in here,” the person recording says, panning the phone to an open toilet next to him. The agency has continued to bar members of the press from viewing the cells, and even arrested several elected officials when they attempted to access that part of the facility in September.

These are all people who, at least for the time being, are in the country legally. They may have crossed through a formal border point or hopped a fence, but at some point they have put their faith in the legal system and declared themselves to the government. They have asylum claims, green card applications, work permits. The government knows who they are and where they live. Their names are on a docket; their information is in online systems and paper rolls. They are, by any reasonable definition, attempting to immigrate “the right way,” as the saying goes.

“Every day, these people are being forced to make impossible decisions,” Paloma, another observer, told me. It used to be that if you followed the system, you had a reasonable shot of a good outcome: the right paperwork going through, an asylum claim being granted. At the very least, you would be treated with a general sense of professionalism and courtesy, in exchange for attempting to navigate the system as it was designed. But paperwork and filings can no longer keep immigrants from being thrown in a cell, and an administration promising to scoop up the “worst of the worst” is instead penalizing those who have done their best to follow the rules.

The fear is primal. The masked agents are hunters, looking to strike whenever someone vulnerable leaves the group.

In order to remain part of the legal process, every immigrant assigned a court appearance at 26 Fed must run this gauntlet: get to the building, find the courtroom, then walk past a group of flashing press cameras and looming federal agents. Paloma said she had seen a pregnant woman wait for hours, terrified to leave the waiting room. Another observer told me that a woman whose case had been approved by a judge had broken down in tears, sobbing hysterically, because she was too afraid of the ICE agents to leave, despite possessing documents that ostensibly protected her from deportation. A priest eventually managed to help the woman leave, half carrying her down the hallway. If an immigrant cannot face this, their only choice is even worse: skip court, remain in the country, and risk being found and deported at any time with no chance of ever being able to return.

“What the Trump administration is doing is tricking people to go to court and then detain and deport them,” said Murad Awawdeh, the president of the New York Immigration Coalition, a nonprofit group that works on immigration issues in the city. “Court used to be a refuge for the rule of law, not a trapdoor. What’s happening [there] isn’t justice. It’s state-sponsored intimidation. It’s always been about cruelty, which is the point. It’s never been about the safety and security of this country.”

The pressure of this situation eats away at everyone, but none more so than the people waiting for their time in front of the bench. You can see it in their faces, their bodies, the way that they speak. I watched a kid, messing with a phone, accidentally hit play on a video with the volume up. The teenage girl next to him—his sister or cousin—snatched the phone instantly, silencing the noise and looking around in fear, her leg bouncing up and down in her seat. A Haitian father pushed one of his kids in a stroller to the bathroom, as worried observers watched him leave. Another man walked down a hallway alone. One of the observers, a lawyer, tried to follow him to see if he could do anything to help. “I can’t communicate with him,” the lawyer said to another observer, frustrated. “He only speaks Haitian Creole.” The man disappeared around a corner as security guards shooed the lawyer back to another room. The fear is primal. The masked agents are hunters, looking to strike whenever someone vulnerable leaves the group.

On many occasions, they don’t even wait for that. In recent weeks, agents have physically clashed with immigrants and members of the press, sending one news photographer to the hospital. In September, an ICE agent violently threw a woman to the ground in an altercation in the hallway, forcing the agency to issue a rare statement on the conduct of its officers, calling the incident “unacceptable and beneath the men and women of ICE.” The officer was relieved of his duties during an investigation, a concession decried by the most bloodthirsty supporters of ICE’s deportation campaigns. He was back at work just over a week later; another reporter pointed him out to me in the halls on Friday.

Alexander Sammon

It Was at the Center of Endless Right-Wing Conspiracies. It Just Closed. Its Legacy Keeps Getting Darker.

Read More

The people who are grabbed are often told the exact same thing by judges as those who leave free, observers told me. Initially, many of the deportation arrests happened after a judge “dismissed” an asylum case. Many petitioners did not understand that dismissal meant that their case had not been approved; when they left, ICE agents were waiting to pounce and immediately eject them from the country. But now, observers said, the arrests are arbitrary and frequently mistaken. ICE agents often have printouts with names and pictures of petitioners they want to detain, but they are consistently unable to accurately match them with names on the court dockets. On Friday, for instance, I waited with a press group outside a courtroom for an hour and a half while agents stood outside, joking with the Paragon security guards about how bad the phone and radio service was inside the building. “If y’all need backup, how do you even call each other?” one agent asked. “Cuckoo! Cuckoo! You call through the vents?”

The journalists were waiting around under the impression that ICE was going to make an arrest when the court let out. The agents seemed under that impression as well. During the shutdown, proceedings had slowed to a trickle: I heard of only one arrest on Thursday, and Friday was similarly slow. The afternoon ground to a halt. “Don’t you guys take a break?” one reporter asked an agent. “Lunch break? We’re not even getting paid for this!” the agent responded. “The fuck you mean, ‘lunch break’?” With the government shut down, they were working on the promise of back pay. A Paragon guard, emerging from the elevator and hoping to find an empty floor and a lazy afternoon, saw the scrum of press and ICE guards and let out an audible “Oh, come on!” before turning away.

Earlier in the day, a bored hallway had been laced with tension after a court employee emerged suddenly to take one of the reporters to task. The press corps inside 26 Fed is a strange mix of regular New York stringers—the kinds you see at all protests and goings-on in the city—foreign press, and nebulously employed “independents.” The reporter in question, under fire from an irate supervisor, describes himself on Twitter as the “White House correspondent” for right-wing provocateur Tim Pool’s podcast. The supervisor was pissed: He’d posted a video of an arrest the previous day that showed her face. Everyone was tense. The court employees, broadly, don’t want to be included in this narrative of arrests and oppression, and certainly don’t want to be identified. The press corps has a job to do, but observers say its presence and callous pursuit of images that will sell can make immigrants feel dehumanized. The ICE agents are always there, armed, a constant show of force. Another supervisor came out and tried to defuse the situation, half lecturing, half sympathizing. A friend of mine, a reporter who’s been covering proceedings at the building since arrests began in May, leaned over to me. “Welcome to the DMV,” he muttered.

One of the Worst Cases of This Supreme Court Term Has Been Years in the Making

The Supreme Court Might Net Republicans 19 Congressional Seats in One Fell Swoop

Marjorie Taylor Greene, Welcome to the Resistance

The True Crime Stories You See on TV Are Leaving Out Something Big

Later, outside the courtroom, as the Friday afternoon hearing drew to a close, activity suddenly picked up. A couple of lawyers exited the room and walked to a different door down the hall. The observers had mostly left. The ICE agent joking about his lunch break stood up from the single chair he’d commandeered at a security post. A single Hispanic man left the room, smiling. The ICE agents stared at him, checked their phones. The press members stared at the officers. My reporter friend, who speaks Spanish, chatted briefly with the man leaving as he stood in line for the elevators. The man got in the elevator and left. The ICE agents stood there for a moment longer. The press stood there. One of the officers, a few steps down the hall, took a quick phone call. Then, as one, they turned and headed out. The Hispanic man, it turned out, hadn’t been their guy, and their unpaid day was over.

The reporters groaned and laughed. The security guard reclaimed his chair, sipping on a milky bubble tea. We all took the elevators downstairs and left the building. Outside, several couples were taking photos in the neatly landscaped park in front of the building, across from New York’s Foley Square. The photo shoots were all the same: a man or a woman, grinning, holding up a thick card-stock certificate emblazoned with the seal of the United States of America. Sometimes, even, they’d brought one of those little dollar-store American flags, holding it up proudly, reveling in the best possible outcome of a visit to 26 Federal Plaza: citizenship, in this great nation, tangible proof that at least for now, under our current fragile state of laws, no one can make them leave.

Sign up for Slate’s evening newsletter.