There is a painting of Lumin’s I have not seen in decades, yet I think of it often. It was made in our junior year at the University of Florida. I think the class was called “Painting in the Series.” She was working on a series of paintings on linen, each an abstraction of memories—her childhood, her home, her father. I haven’t seen that painting since 2003, yet sections of it have stayed with me for twenty-three years. Of all the images I witnessed Lumin create since our freshman year, that one is most indelible. It embodied her, the natural world she loved, her magical upbringing in the woods, and the memory of her father—lost only a handful of years before, too soon, too suddenly, to a glioblastoma.

The painting was one of her first on linen, or so my memory recalls. Almost square, around eighteen to twenty-four inches in each direction. It was the first I’d seen her make entirely from memory, without observation. A blue body of water beneath layers of abstracted green leaves, whimsical marks of pink, red, and white leading your eye to a pink mask-like shape in the bottom left corner. During critique, she spoke with love of the home her father built, the forest that held it, the sinkhole she explored, and of her father.

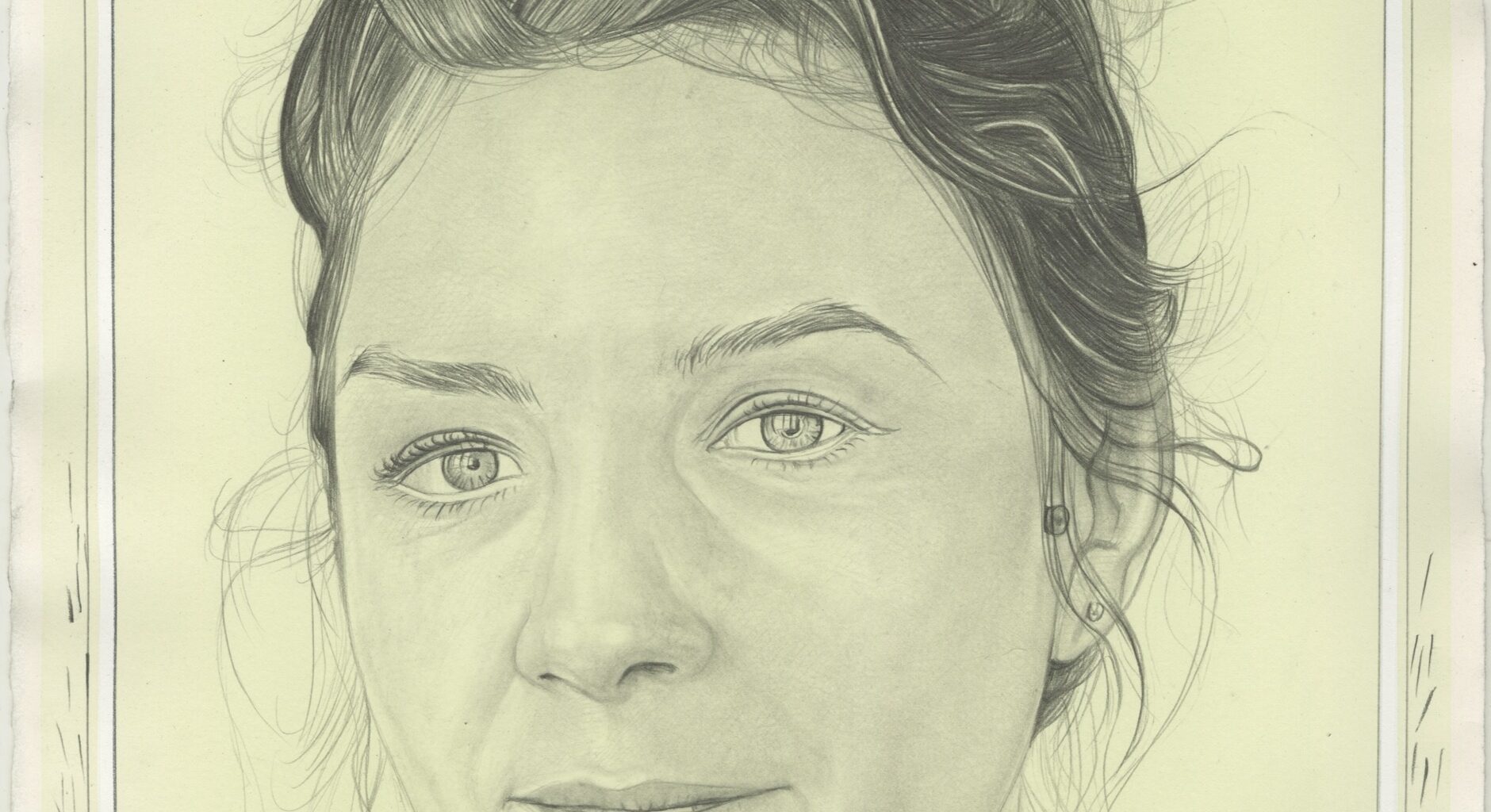

Her senior-year paintings returned to observation, to the present—searching for herself in the sea, in bottled specimens, in her own reflection. Looking back, they feel like a search for who she was outside that childhood home, in a world without her father, and for what her observations could bear witness to. In the years after school, while living in New York before grad school, she painted herself floating within the beauty of the ocean and its creatures.

During the few years when Lumin went to grad school, I lost the closeness I once had with her work, unable to see and talk with her about it regularly. She experimented—first with abstraction, then back to observation, painting structures she built in nature. From the outside, she seemed adrift in her work, as so many of us are in grad school. Risking, questioning, turning outward instead of inward.

For Lumin, painting was process, never a means of capturing a predisposed idea or image. Her images were born through a process of response. Over time the genesis of the paintings shifted, but there is always a tension between recalling, observing and responding. Back in New York, she returned to observation again—candles burning, hanging fruit… Then shifting again, paintings as props and props as paintings, inviting the viewer to interact, to live alongside the work.

When I first saw the paintings Lumin was making in the ten or so years leading up to her recent work, it was like an echo returning. I’d seen them before. I knew them. I had lived them. That painting from our junior year existed in all of these works and in all that followed. There were traces of the marks, colors, and gestures within that earlier painting. They were alive, honest, present. They felt like everything I love about Lumin.

On the backs, a handful of canvases bore poems she wrote of her memories, of her lived experience. The poems gave her paintings their shape, their color, their space, they lent the work an intimacy that felt known. Poetry encapsulated what Lumin wanted of her paintings, a timeless narrative of a fleeting moment. It was a way for her to jot down moments with specificity, without logic. Something she could endlessly return to and pull from while working on a painting. Looking back, it makes sense that she reached this body of work after becoming a mother. As mothers, we are able to process so much of our earlier selves, our experiences and losses. We can finally see ourselves from outside ourselves. In a poem about her own mother, Lumin writes, “She looked into this flower, each time I imagine it differently and infinity opened up before her.”

Later, as her subject shifted again to the natural world, poetry became inseparable from observation. No longer serving as a point of departure for her paintings, writing was woven into her practice of daydreaming, witnessing and processing her experiences. We caught glimpses of her poetry in her titles. Forget the stars, all you need is here on Earth. I look for you in everything. Flowers and skeletons, each alive, each dying. Each inviting us to revel in their beauty.

It seems too simple to say that all her work was part grief and part celebration of her father, but isn’t it in some way? At the very least, it was a key component of it—and also her love for existence, for her family, for us, and for the inevitable absences to come. Memory and the present, indistinguishable at times, impossible to unwind. All at once a part of us.

My heart aches when I think of that painting buried in my memory. I want to remember it all—each mark, each gesture, each memory. But memories change elusively over time: less factual, no less true. My memories of my dear friend Lumin are the same. I try to hold them as they are, but the colors shift, the time and place blur, the shapes transform. And yet they remain, part of my existence, my story, my images—in one way or another.