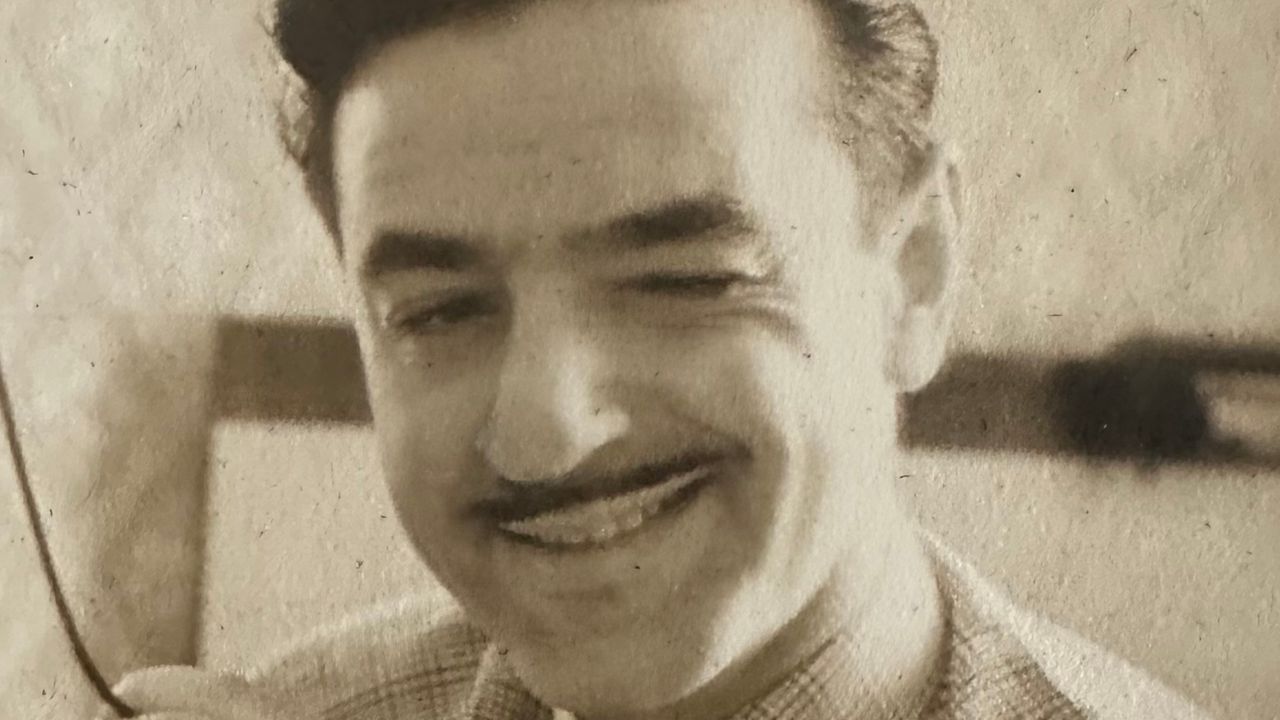

Daniel’s commercial failure as a novelist impelled him to move to Los Angeles to try writing for the movies. He succeeded, if not epically, specializing in crime and caper flicks and earning an Oscar for Best Story for “Love Me or Leave Me” (1955), starring Doris Day as the singer Ruth Etting and James Cagney as her hoodlum husband. In his later years, Daniel published several reflections on Hollywood and the long path he’d travelled from humble Williamsburg. “Within a short radius of where I lived, South Second Street between Hooper and Keap, there were no fewer than seven movie theaters,” he wrote in the Times in 1971. “The bill was changed every day or every other day, I can’t remember which, and almost all of us, children born, went regularly to the Hooper twice a week, and a good many of us went even more often.”

It’s this movie-drunk aspect of his and Eli’s childhood that provides a window into my grandfather’s psyche. Daniel, in the Times piece, contemplates the notion that “the movies had their great rise because, by an accident of timing, they came into being just as the flood of immigration was at its height.” But that wasn’t the real pull of the cinema, at least not for the Fuchses. “What these pictures did—with their virility and vigor, their command of life and consistently positive statements—was to act against the fear that possessed and constricted us,” Daniel writes. “It was a vague, inchoate fear that came down to us almost unconsciously from our parents, a fear that came out of Old World oppressions, from the difficulties of life in the New World, and from the hardships our parents and grandparents had undergone in transferring themselves and their families from the Old World to the New—it was as though the feat of immigration had used up their strength and courage.”

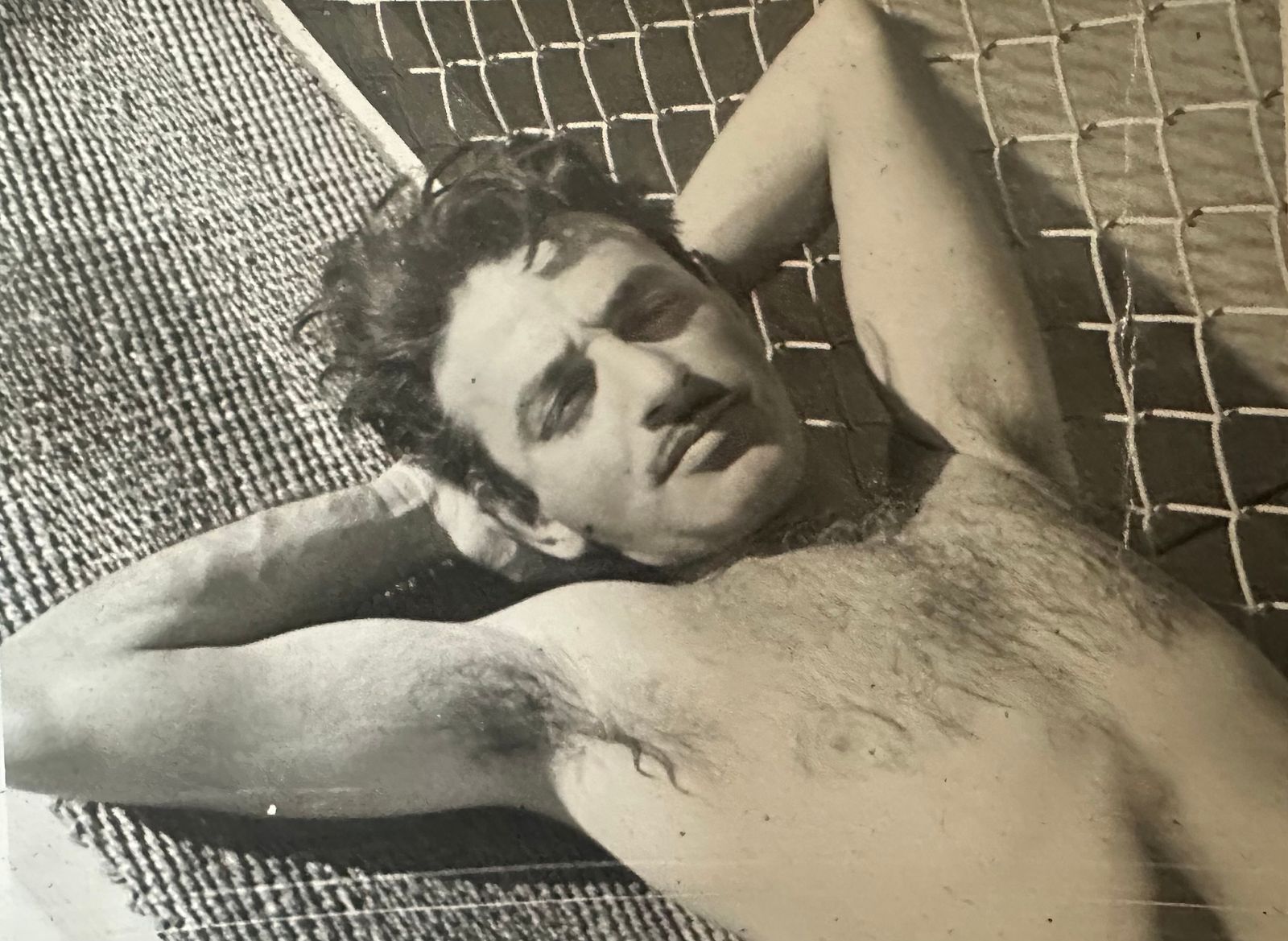

Eli Fuchs’s brother Daniel, an Academy Award-winning screenwriter.

For someone like Eli, then, projecting movie-star-like virility and vigor was an exercise in social advancement, in distancing himself from his babushka forebears’ grim reality. And the difficulties of life in the New World? The Fuchses knew difficulties. Eli and Daniel were preceded by four brothers. In 1909, just a few days after their mother, Sara, gave birth to Daniel, one of these boys, four-year-old George, fell to his death while playing on the roof of their tenement building on the Lower East Side. Their apartment’s location had afforded my great-grandfather Jacob a conveniently short commute to his job—he operated a newsstand in the lobby of the newly erected Whitehall Building, on Battery Place—but George’s death precipitated the family’s move to Williamsburg, which, jumbled as it was, was a step up from the dangerous slum they’d been living in.

His birth overshadowed by his family’s greatest tragedy, Daniel found succor in movies and willed himself into the dreamworld of Hollywood. On sunny afternoons there, he wrote in 1971, recalling his giddy days as a newcomer, he would roam the Warner Bros. lots, watching “the studio bravos in their costumes at their perpetual play.” Eli’s life, by contrast, remained ordinary, that of a career civil servant who moved his family from grubby Brooklyn to suburban Highland Park, New Jersey. A tinkerer, he rented a workspace in New Brunswick, across the Raritan River, in which, off duty, he invented contraptions that he hoped would catch on and propel him to bigger things. One such machine reproduced a single photo as a sheet of fifty stamps bearing the photo’s image. He advertised this service in the back of cheap magazines, under the name Stampix. You’d send in a photo of, say, your newborn baby, and, for a buck and a self-addressed stamped envelope, you’d get your photo back and fifty little adhesive portraits suitable for birth announcements.

Stampix did O.K. but not great; Eli sold the business in 1947. The one huge curveball in his biography is that, in the fifties, he took the plunge and fixed his nose. No, it’s stranger than that—he splurged on rhinoplasty not only for himself but also for his wife and daughter.

My then teen-age mother, whose birth nose looked not unlike her father’s, hadn’t even expressed a desire to have work done. She was a studious and outdoorsy girl who later became a research scientist at Johnson & Johnson. “My parents were always trying to get me to be more glamorous, and I wasn’t interested,” she told me. “But I did it for them, because it made them happy.”

The Eli I knew was distinguished in appearance, but I am sorry never to have seen in the flesh the nose that so tormented him. It’s strange to think of my grandfather, who kindly guided my siblings and me through the Smithsonian museums and took us out for Baskin-Robbins, as a man possessed of an influencer’s vanity. But the evidence is there, in those stacks of photos. He lived a decent life, but his big dreams remained dreams, their fullest realization captured in the selfies he left behind.