Jen Percy is a National Magazine Award-winning journalist whose book, “Girls Play Dead,” expands upon her landmark New York Times Magazine cover story, “What People Misunderstand About Rape.”

Jen Percy is a National Magazine Award-winning journalist whose book, “Girls Play Dead,” expands upon her landmark New York Times Magazine cover story, “What People Misunderstand About Rape.”

Drawing on original reporting, years of conversations with survivors and her own life story, Percy illuminates the psychic disconnect that accompanies trauma: how the mind protects the self through fragmentation and how silence and passivity (what is sometimes described as “freezing”) have evolved as survival strategies.

Percy explores phenomena like tonic immobility and collapsed immobility — often misinterpreted as consent or indifference — and shows how deeply ingrained myths around resistance shape legal and cultural responses to harm. She also examines how sexual trauma corrupts storytelling itself, making survivors’ accounts seem fractured or surreal and therefore less credible to institutions demanding coherence.

At a time of heightened cultural reckoning, Percy’s clear-eyed, compassionate reporting and vulnerability feel especially urgent.

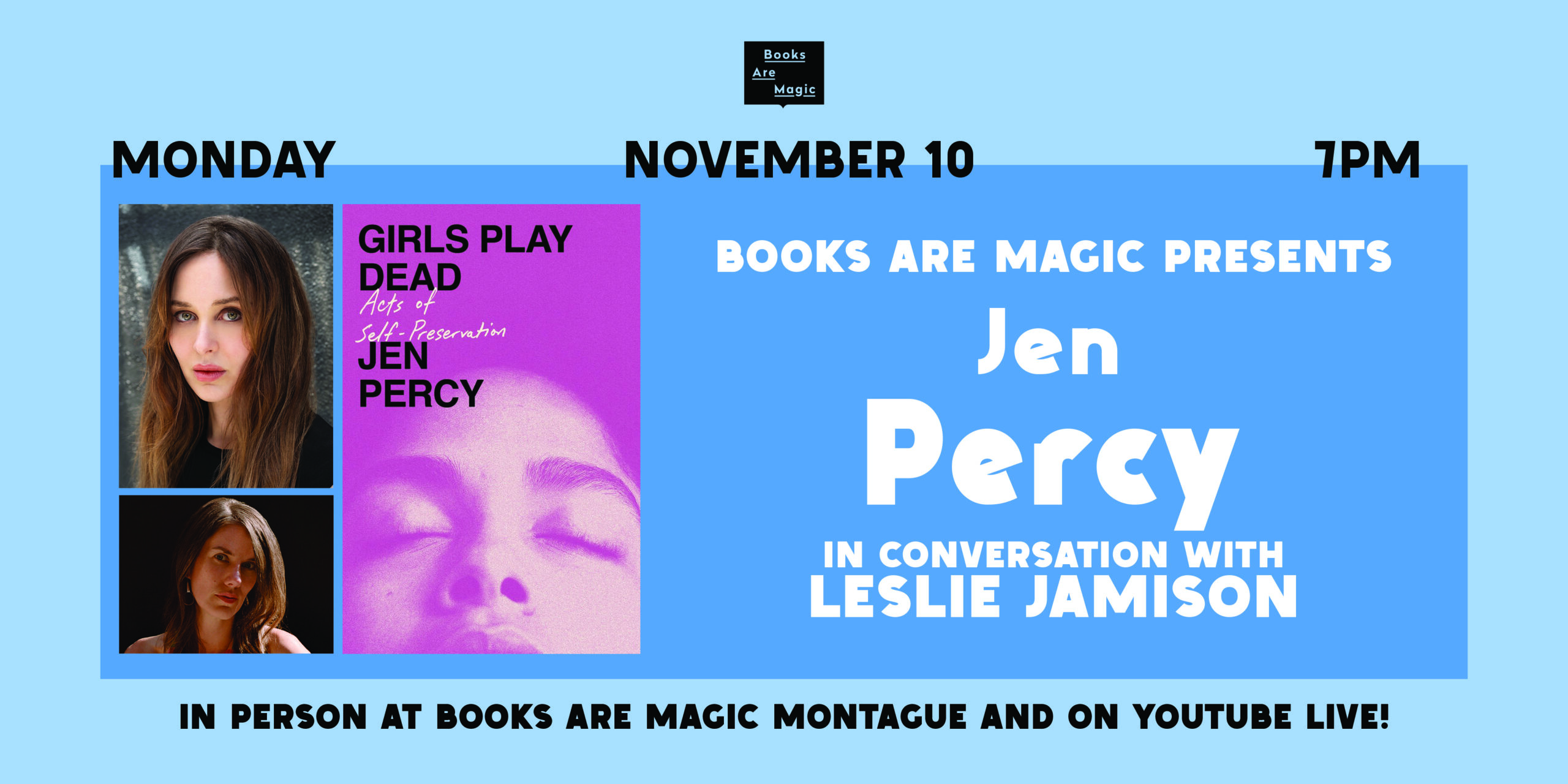

Percy will discuss the book with author Leslie Jameson at Books Are Magic in Brooklyn Heights on Monday, Nov. 10. A signed copy of the book comes with each ticket.

“Girls Play Dead” is a richly expanded and reimagined version of your New York Times Magazine cover story, “What People Misunderstand About Rape.” What made you want to stay with this subject, and how did your approach evolve as you turned the article into a full-length book?

I was working on the proposal for this book years before the article, but the writing was mostly memoir. I was writing about the ways I responded to fear in the context of sexual harassment, assault or male power that was confusing to me.

One day, I started watching videos of animals playing dead and I learned sexual assault victims did the same thing in response to rape. It was an involuntary response that caused full body paralysis. I thought the lack of public information about this response was important and urgent enough to pitch to a magazine.

At first, my editors didn’t think it was a real response to rape, and I understood where they were coming from. A response that renders a woman paralyzed and mute sounds like something from the darkest fairy tale — yet it was real, and no one was talking about it.

I spent another year gathering evidence before I got the assignment. I knew the science had to be airtight.

How did your research for the article shape the writing of the book?

The intense reporting required by the New York Times Magazine helped introduce me to all the top experts studying victim behavior.

I got to hear them talk about all the “strange behaviors” they’d encountered. Some of them were things I wanted to write already because either I had experienced them or my friends had, but I learned it would be important to incorporate science, psychology, history and a variety of survivor’s voices into the book as well.

I went to conferences and attended trainings. I learned from scientists, psychologists and lawyers and I kept a journal of all the counterintuitive behaviors they wrestled with on the job.

When I started talking to survivors, I found even more baffling responses, such as post-traumatic convulsions. Each conversation revealed a thread that led to the next section or chapter. I was working on the book and the article at the same time, but the book transformed what I was working on from memoir to reportage and cultural criticism.

Can you walk us through the concepts of tonic immobility, collapsed immobility and psychogenic seizures? How do these involuntary responses function in moments of trauma and its aftermath? Why are they so often misread as consent, passivity, intoxication or hysteria? Are there growing efforts to educate law enforcement, judges and the public — future jurors! — about these trauma responses?

Tonic and collapsed immobility are little known responses to terror that render a person completely unresponsive. While tonic immobility leaves a person stiff and mute, the other leaves her floppy and mute. It’s quite terrifying. I was shocked when I first learned about them.

Wouldn’t it be awful to be paralyzed when all one wants to do is kick and scream? But they are brilliant evolutionary adaptations to predators (who don’t like dead meat). These are responses that make people seem like corpses for a few minutes at least.

Once the danger is past, we spring back to life. It’s clear that anyone experiencing these behaviors could be misunderstood as consenting. Why would you be having sex with a woman acting like a corpse? Maybe some people are into this, but it’s really just an excuse or a myth patriarchal society has allowed to thrive.

The psychogenic seizures are a horrifying and debilitating post-traumatic response to rape that eerily calls back to Charcot’s hysteric women. The weight and harm of this history makes it really difficult for women to recover.

I came to think of the convulsions as the opposite of freezing — a delayed response to the terror of being held captive by immobility, as if all the fighting and kicking they wanted to do at the moment of freezing was finally happening.

In a book filled with anonymous and everyday voices, you also engage with high-profile survivors like Lady Gaga, Brooke Shields, E. Jean Carroll and Taylor Swift. What value do you see in celebrities sharing their experiences of trauma, especially in shifting public understanding of responses like freezing?

I think it’s important to see how common these responses are across class lines. It’s also a reality — whether good or bad — that when a celebrity speaks on something, especially sexual assault, people seem to listen.

I didn’t talk to celebrities directly and I didn’t seek them out. They were just the loudest voices when I first started my research. I was scanning the news for language about freezing, and whose voices were most prominently featured in the news? The celebrities.

I gathered their quotes as a beginning, and then reached out to ordinary people to see if the patterns were the same, and they were.

You write about “unwanted consensual sex” — sex that occurs without coercion but also without desire, often as a response to social conditioning. How should we be rethinking consent in these murky, culturally sanctioned zones? What are the costs of only speaking about sex in the binaries of good or bad, wanted or coerced?

It’s really important that we start expanding the vocabulary we use to talk about unwanted sex, because right now, it feels like the only word available is “assault.”

I have quite a few experiences I would never call sexual assault but that I experienced as harmful. These aren’t things I would bring to a police officer or anything, but they are experiences I want to talk about and understand.

It feels like that’s not really something people think is worth a serious conversation. I thought it was fascinating to learn that so many college students — men and women — were following gendered scripts that led them into places of harm. None of these moments were assault or rape, but the students experienced a lot of psychological distress from having sex they didn’t actually want. Part of that distress came from a lack of meaningful vocabulary to talk about the experience.

How does systemic inequality — poverty, racism, lack of access to care — compound trauma? How do these failures affect both legal outcomes and personal healing?

Trauma is measured not by the event but by its impact on the person.

If someone is already experiencing systemic inequality, the impact of any single stressor (or accumulation of stressors) is going to be more severe. When you’re mentally and emotionally on alert from the stressors of inequality, it creates a physiological responses that can cause damage to the body. Over time, it contributes to anxiety, heart disease, depression or cognitive impairment.

Early trauma can alter the architecture of the developing brain which can impact behavior and stress responses. Historical trauma can create health inequities centuries later.

Those living in poverty are at a much higher risk of being victims of intimate violence. We often criminalize women for the very strategies they employ to keep themselves out of poverty or to feed their families: stealing food, sex work. We blame women for keeping themselves safe by staying in abusive relationships (so as not to get killed or so their children don’t starve), and when they do fight back, we criminalize them for the violence they’ve committed.

We also know that Black women are more likely to be exposed to traumatic experiences than other racial groups but they are less likely to report sexual violence, less likely to be believed when they do, and less like to have their cases go to trial or end in a conviction.

Much of your book wrestles with the hope that if survivors just tell their stories the right way, they will be heard and believed. But what about when they are believed and nothing changes? What do we do with the disillusionment that follows?

I think it’s important to sit with that idea and feel its weight, because it’s a very heavy feeling.

In certain contexts, the more powerful person gets to dismiss certain stories as being unimportant. The women I interviewed who were in prison for self-defense show that we’re still living in a society that doesn’t value their stories. It’s not about believability. We believed them and nothing changed.

Their stories could help someone else down the road, and they are still testimonies for the historical record. The women understood that on some level. It didn’t make it easier or better, but there was still an agency that came with telling their stories.

Overall, we put a great deal of faith in storytelling, and we bet on the power of an individual’s story to be heard. While writing this book, I started to see how this is sometimes a romantic notion for the privileged. I remember talking to the head of a nonprofit who did a lot of work with women and girls in places like Haiti and Sudan. She told me the best thing a girl could do was to “not tell her story.” I’ve never forgotten that. It was the opposite of what many Americans are taught and the opposite of what we are fighting for. The head of the nonprofit explained that the girls who told their stories were killed because of it. What happens to a story and the storyteller is also about cultural, economic and racial context.

‘Girls Play Dead.’ Photo courtesy of Beowulf Sheehan

‘Girls Play Dead.’ Photo courtesy of Beowulf Sheehan

Where in Brooklyn do you live and what brought you to the neighborhood?

I just moved to Cobble Hill and hope it will be my forever neighborhood. I’m from a small town in Oregon, so I came here to get away from where I grew up. I stayed for the diversity, the food and access to the arts.

How do you hope the book will resonate with Brooklyn audiences, both at the Books Are Magic event and in general?

I hope the book helps spark a conversation that extends the #MeToo conversation beyond criminal sexual assault and sexual harassment in the workplace.

“Girls Play Dead” explores women’s sometimes absurd and unbelievable responses to trauma and looks at how these responses shape stories in the aftermath of sexual violence. I hope readers also see how these topics extend behind the container of the book; namely how the material can be in conversation with our current political moment, which everyday threatens the humanity of women, LGBTQ+ and minorities.

What are some of your favorite spots in your neighborhood?

The Brooklyn Cat Cafe for sure. There are cats everywhere and just when you think it can’t get any better you find out there is also a bunny, a turtle, a chinchilla and two really cute rats.

I also love the Brooklyn promenade because you can smell salt water and see the sky.

How is Brooklyn supportive of your career and your writing?

Having so many writers in one location makes Brooklyn feel like a little campus or community, and that’s energizing on its own. And, of course, all the great bookstores that help get the word out about local authors and support our books. Just knowing I can go to a reading almost every night of the week makes the writing feel a little less lonely.