Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to get essential news about NYC’s public schools delivered to your inbox.

New York City schools handed out fewer suspensions last year, the lowest rate since the pandemic forced school buildings to shutter, according to new Education Department statistics.

Overall, schools issued 27,143 suspensions during the 2024-25 school year, down 2.1% from the year before.

The decline was driven by a big drop in superintendent suspensions, which run six days or more and are served at outside suspension sites. Students received those lengthier punishments nearly 5,600 times last school year, down from about 6,200 the year before — a 10% decline.

Principal suspensions, which last for five days or fewer and are typically served in school, were issued more than 21,500 times, only slightly higher than the year before. (The figures do not include charter schools.)

Lengthy suspensions have recently drawn increased scrutiny. Legal Services NYC, a public interest group, filed a lawsuit in May alleging the city uses an inappropriately low standard of proof in suspension hearings, violating the U.S. Constitution. (City officials have moved to dismiss the case.) Schools have also routinely suspended students with disabilities for longer than legally allowed by federal law, a Chalkbeat investigation found.

It’s unclear what drove the decrease in lengthy punishments last school year. Schools typically must get approval from a central office administrator to issue a superintendent suspension.

“There haven’t been any clear policy changes,” said Rohini Singh, the director of the school justice project at Advocates for Children, which helps families to navigate the suspension process. “Certainly, we’re happy to see that the overall number of suspensions is decreasing.”

Still, Singh noted that troubling disparities persist.

About 39% of all suspensions were issued to Black students and a similar share went to students with disabilities, even as only 19% of the city’s public school students are Black and 22% have a disability. Latino students, who represent 42% of the student body, were suspended roughly in line with their share of the population. White and Asian American students were far less likely to be suspended compared to their share of the population.

Children living in foster care were at least four times as likely to be suspended as their peers, an uptick from last year, according to an analysis from the group Advocates for Children, which has pushed for reforms to school discipline policies.

Inspiration, advice, and best practices for the classroom — learn from teachers like you.

Across all of our bureaus, Chalkbeat reporters interview educators with interesting, effective approaches to teaching students and leading their schools. Get the best of How I Teach sent to your inbox for free every month.

An Education Department spokesperson celebrated the decline, though did not directly address the disparities.

“We are proud that over the past year, we have decreased overall suspensions,” department spokesperson Jenna Lyle wrote in an email. “We are continuously working towards encouraging schools to address any issues in a positive, supportive, and less punitive manner where possible.”

Many — though not all — studies suggest that suspensions hurt the suspended students academically. One study based on New York City found that removing students from their classrooms contributed to students passing fewer classes and increased their risk of dropping out.

After the pandemic, some observers feared suspensions might spike as concerns about student mental health and behavior grew. Others worried that Mayor Eric Adams’ tough-on-crime posture toward public safety could ripple into schools, though there have not been any major policy changes to the city’s discipline code under his watch.

His predecessor, Mayor Bill de Blasio, overhauled the code to reduce suspensions for minor infractions and cap most suspensions at 20 days. (Suspensions can still run for months or even an entire school year in some cases.)

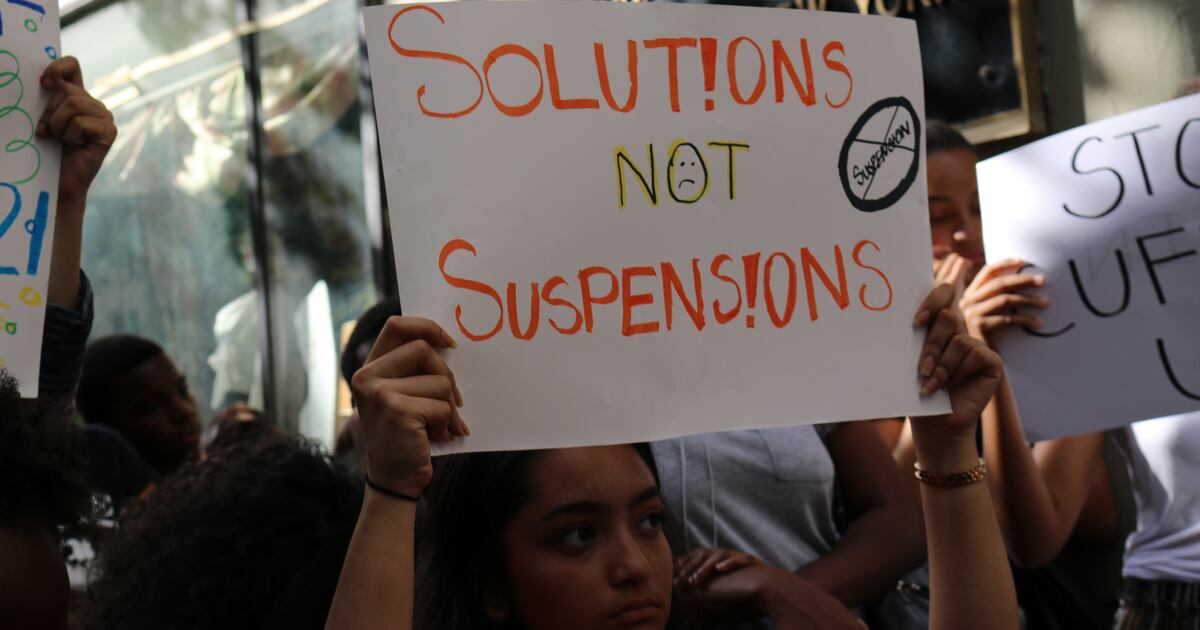

Groups that oppose suspensions have successfully pushed the city in recent years to invest in alternatives such as restorative justice, which can include peer mediation and other methods of talking through conflicts. Some educators have countered that suspensions are an important tool for maintaining a safe learning environment and the city has not done enough to support alternative approaches.

Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani has said little about how he would approach school discipline, though his campaign platform emphasized mental health support for students. Some advocates called on the incoming administration to boost funding for those programs and ensure long-term support for other mental health initiatives that have had to fight to maintain funding each year.

“We’re encouraged by a lot of what we’ve heard, but it still remains to be seen what’s going to happen,” Singh said.

Alex Zimmerman is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Alex at azimmerman@chalkbeat.org.