Most noticeable, amidst the magical realms and unexpected forms that fill the loft in Brooklyn, are Sikander’s women. Women behind diaphanous veils. Women in flowering gardens.

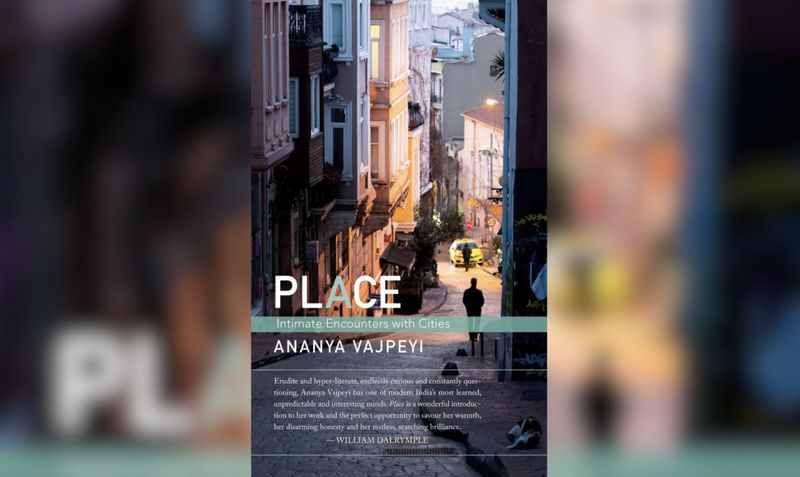

The following is an excerpt from Place: Intimate Encounters with Cities by Ananya Vajpeyi, published by Women Unlimited Ink. (Pp: 239, Rs 625)

The Indo-Persian Sublime

Down Under Manhattan Bridge Overpass. DUMBO, Brooklyn. Old warehouse buildings full of workspaces for architects, painters, sculptors, new media practitioners. Massive steel bridges stretched out over the water. Incessant stream of vehicles, flowing on the highways like corpuscles. Dull roar of heavy machinery on gigantic construction sites. Overwhelming Manhattan skyline. On the sidewalk, a film crew at work. Fluorescent orange roadworks to divert cars away from the delicate mesh of camera equipment, the street awash with building workers, actors, artists, traffic policemen. June noon time, humid and heady; the beating heart of New York City.

It is 2004, about 15 years after I first began listening to qawwali. Here in this gritty part of Brooklyn is Shahzia Sikander’s studio. It has a high ceiling; it is lit by a very large window whose glass is grimy with age. The room is crowded with canvases, wooden frames, art books, paint, CDs, brushes, boards and the uncontainable creativity of its occupant. She is a slight figure, dwarfed in her own loft space, but her mastery of the miniature form is quite unprecedented. Far from Delhi, in a city without gardens, once again, the Indo-

Persian sublime takes shape. Painting is perfection.

My arms are fair

My bangles, green.

You took me by the hand

You pulled me close.

My bangles broke

Green

Glass.

What Khusro did for poetry in the Indo-Persian world, no one else had done until his time. He made it, fashioned it in the languages of the Gangetic plains that until then did not have a poetic register. This was a feat akin to divine intelligence creating the world. We cannot even begin to comprehend the novelty, the effulgence, of making poetry for the first time in a tongue of everyday commerce and conversation. For us language is a worn coin, cheapened by use, saturated with significance and depleted in value. Code floods our world, drowns all meaning. We can scarcely even imagine, let alone remember, such an inaugural minting of poems as Khusro achieved in the 13th century.

Who says poetry

Cannot be written in Hindavi?

That Persian alone

Is worthy?

Persian is fine wine

Hindavi crude liquor

But we know which

Is more intoxicating!

Something reminiscent of the mystery of making brand new poetry goes on in Shahzia Sikander’s studio. Visions opening in her mind’s eye unfurl on gossamer sheets of paper. Most noticeable, amidst the magical realms and unexpected forms that fill the loft in Brooklyn, are Sikander’s women. Women behind diaphanous veils. Women in flowering gardens. Women crowding around a blue-skinned god. Women breaking out of the framed portraits of princes in profile. Armed women, bearing weapons. Many-armed women, goddesses on earth. I am reminded of Gayatri Spivak in her celebrated essay, “Moving Devi”: “Such powerful females, improbably limbed.”

The charm of Sikander’s world, with its welter of women, is ineffable; its rigour, breathtaking. As at the singing of a qaul—the ‘word’ of qawwali, its opening call—tears rise out of their home in one’s heart, into one’s eyes, where they must remain.

You looked in my eyes

The unspeakable was uttered.

I drank deep

From your brew of love.

I was intoxicated.

Stranded in the present

I can be in Delhi, but not in the city that was when Khusro lived and wrote and sang and composed and invented and imagined and made from his mind, meaning and music. Fragments of Khusro’s Delhi surround me and yet its totality is irretrievable. One senses monsoon winds bearing their burden, but they are remembered more clearly than they are seen. One glimpses parrots among the rain-harassed trees in the Lodi Gardens, but they are gliding to their extinction. One smells the Yamuna, two notional banks for a vanished city, filthy trace of a river that was murdered. One hears old qawwals at Nizamuddin’s shrine, their voices broken with thirst, pollution, poverty. I can, however, go into the crucible that is New York City and visit Sikander’s space where she brings alive, on a far continent, in another age, the Indo-Persian sublime.

She gives me directions over our cell phones. I take the subway across the water from Manhattan. She meets me at the first station on the other side. We walk in the sunlight across a park, under a bridge, down streets shaded by tall buildings. She shows me a new animation CD she is making on her iBook, recently dropped and partially broken, its hold on data somewhat precarious. She tells me that it takes her two years, sometimes more, to make work for a show. Making work. Every era has its flavour, its own sweetness on one’s tongue. Roar of storm clouds in Sultanate Delhi; roar of traffic in new millennium New York. Qawwali pounding in my ears; miniature painting piercing my eyes.

The novelist Orhan Pamuk has written of sharp needles, of dark workshops, of the blindness and the betrayal, the heresy and the epiphany that constituted the lives of miniaturists in Safavid Iran, in Ottoman Turkey, in Mughal India. In My Name is Red Pamuk writes of Istanbul long ago. Sikander exhibited in the Istanbul Biennale in 2003. Her paintings were displayed in a bank, as befits works that are precious. On the walls of a vault, a charming tale she had painstakingly animated folded and unfolded, her monsters and men came together and fell apart in exquisite detail, with her trademark intricacy, her signature humour; a two-dimensional puppet show on Istiklal Avenue. I have been there too, to Istanbul of the Blue Mosque, I have seen its minarets and bridges, its cobbled streets and covered markets. Two years later Pamuk would come out with another book about his beloved city, Istanbul. Khusro lived in Delhi long ago. Sikander lives in New York now. Beauty is precisely that which comes across oceans, ages and media, with grace, perfectly.

This article went live on November twenty-second, two thousand twenty five, at twelve minutes past six in the evening.

The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.