Once a month, when the Brooklyn Children’s Museum is closed to the public, it welcomes a special group of visitors: parents incarcerated at Rikers Island and their children.

The Haven: Reunification program, hosted in partnership with the city’s Department of Correction, gives kids and parents a comfortable, welcoming place to play, bond and learn during long periods of separation. It was designed to blunt the impact of incarceration on children and combat recidivism after parents are released.

Atiba T. Edwards, president and CEO of the Brooklyn Children’s Museum, said the program aims to give families a sense of autonomy during their visits.

The visits are designed to give parents and kids a sense of autonomy, said Brooklyn Children’s Museum president Atiba T. Edwards. Photo courtesy of Winston Williams/Brooklyn Children’s Museum

The visits are designed to give parents and kids a sense of autonomy, said Brooklyn Children’s Museum president Atiba T. Edwards. Photo courtesy of Winston Williams/Brooklyn Children’s Museum

“When they’re on Rikers, they don’t have choice, they don’t have a lot of agency,” he said. “The same way we create a museum that is rooted in agency for children, what would it look like if we provide a sense of that for the parents who are incarcerated?”

At the request of the DOC, the program is hosted in a self-contained exhibit area. But, within that space, parents and kids are given free choice to explore the exhibit, play, do art projects and workshops, or just sit together to read and talk.

“I think we, as adults, don’t really think about play as a common factor in our existence, but it shows up in everything we do, it shows up in the music, it shows up in the places we go,” Edwards said. “Having these families spend two to three hours at the museum, playing together, it takes us back to the core essence of who you are.”

For both children and parents, the most joyful experiences are made of small moments, Edwards said.

Small, joyful parents boost parents and kids. Photo courtesy of Winston Williams/Brooklyn Children’s Museum

Small, joyful parents boost parents and kids. Photo courtesy of Winston Williams/Brooklyn Children’s Museum

“When some of the best moments happen is like, watching your child go down the slide, and they’re like ‘Come on, daddy, come after me,’” he said. “And then the adult goes down the slide after, and this moment of glee and joy is so, so beautiful.”

To capture those moments without putting families under the microscope, the museum snaps instant photos for each family to take home after their session. The activities, too, create tangible connections between the incarcerated parent and their child.

“Every month, we try to make sure there’s an art project they can make alongside, so the entire family has the opportunity to make a thing, and then the child takes that home,” Edwards said.

At a recent session, they created and painted terra-cotta pots and planted them with hardy, long-lived spider plants.

Parents and children can explore the museum’s exhibits together during their monthly visits. Photo courtesy of Winston Williams/Brooklyn Children’s Museum

Parents and children can explore the museum’s exhibits together during their monthly visits. Photo courtesy of Winston Williams/Brooklyn Children’s Museum

“There is a high likelihood that a year from now, that spider plant is thriving, and that family can always say, ‘Oh, I made this with my mom and my dad,’” Edwards explained. “Whenever the parent returns home, they’re like, ‘Oh, yeah, I remember we made this together at the Children’s Museum.’”

Each session also offers snacks from local Brooklyn businesses. There’s an element of choice there, too, Edwards said — incarcerated people can’t always choose what they eat, but at the museum, there’s a selection of cookies, juice and chips.

BCM’s core audience is children ages 5-8. But so far, across four sessions — two with moms and two with dads — the age range has varied. In some instances, 20-year-olds have accompanied their younger siblings on a visit to see their parents.

After each session, organizers interview the participating parents in a group setting and individually to assess the real, qualitative impacts of the program.

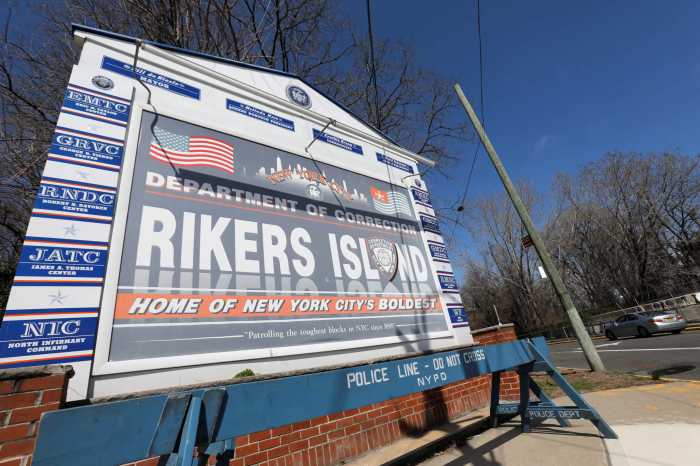

The program is designed to prevent recidivism and blunt the impact of incarceration on children. Photo courtesy of REUTERS/Mark Kelly

The program is designed to prevent recidivism and blunt the impact of incarceration on children. Photo courtesy of REUTERS/Mark Kelly

“One of the common themes is like, ‘Look, spending the time reminded me of how much I love to be with my family, and how much I’m missing that, so I want to make sure I’m getting out of here as quickly as possible and staying out of here,’” Edwards said.

One parent said they were “done with the prison life,” and just wanted to get out to spend time with their daughter.

They try to interview the children, too, but those conversations are more difficult.

“It’s a hard goodbye,” he said. “So it’s often a tearful goodbye … so we generally just ask them, ‘How are you feeling?’”

The responses are very similar, he said. Children are happy to have spent time with their parents, and happy to have a project they made together, even after they’ve been forced to separate again.

The DOC chooses which parents will participate, Edwards said. There are more men incarcerated on Rikers than women, and many of the moms have been able to attend both mothers’ sessions so far, while fathers might be able to attend less often.

“I don’t know all the inner workings, how they earn the privilege, but for some of the families who have done it once, I’m sure they really want to try to do it as often as possible,” Edwards said.

The DOC first pitched expanding their reunification program in 2019, Edwards said. The COVID pandemic derailed their plans, and by the time it was safe to start the program up, DOC had lost its funding.

BCM hopes to expand the program as time goes on and host more frequent sessions. Photo courtesy of Winston Williams/Brooklyn Children’s Museum

BCM hopes to expand the program as time goes on and host more frequent sessions. Photo courtesy of Winston Williams/Brooklyn Children’s Museum

That’s when Edwards reached out to Gregg Bishop, executive director at Clara Wu Tsai’s Social Justice Fund. The fund agreed to give the museum a two-year, $160,000 grant. As time goes on, they hope to run the program more often — up to two or three times a month. Each participating family gets a free membership, and incarcerated parents are entitled to one when they get out of jail, too.

Haven: Reunification further embraces BCM’s mission of serving the community both inside the building and out, Edwards said.

“It just really warms my heart. It’s almost tearful — in a happy tear way — when we get the green light, and the families walk over to where the parent who’s incarcerated is, and then there’s this great, joyful embrace,” he said. “It’s just another way for us to extend our building so everyone can see themselves in our space, one way or another.”